WASHINGTON – The Department of Health and Human Services’ botched response to rolling out the COVID-19 vaccine for Native Americans caused significant delays in getting the vaccine to urban American Indians, the president of the National Council of Urban Indian Health told a House subcommittee Tuesday.

HHS neglected to ask Urban Indian Organizations for input on the vaccine rollout until a day before the deadline, according to Walter Murillo, president of the National Council of Urban Indian Health.

As a result, he told the House National Resources Subcommittee for Indigenous People, vaccine distribution to urban American Indians was significantly delayed. American Indians in urban areas were unclear whether to get their shots through their state of residence or through the Indian Health Service, Murillo said.

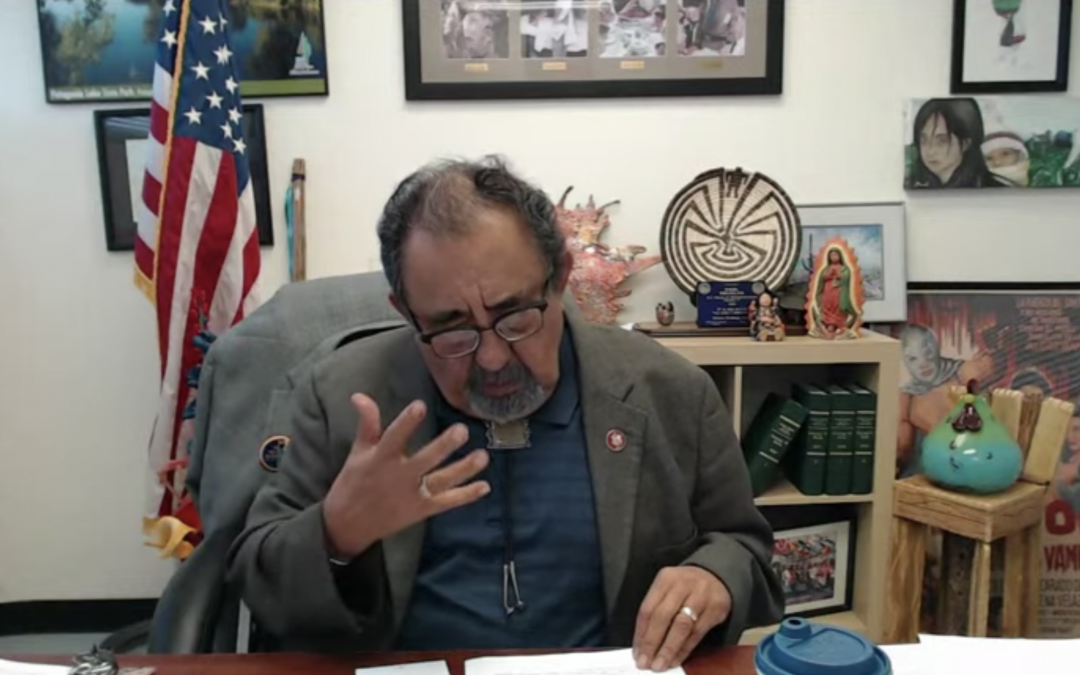

The Urban Indian Health Confer Act, introduced by subcommittee member Rep. Raul Grijalva, D-N.M., would require HHS to consult the 41 Urban Indian Organizations, which are urban-based nonprofits governed by Native Americans to address health care issues, on health care policies concerning the 2.8 million American Indians and Alaskan Natives living in urban areas.

The Indian Health Service is the only HHS agency that confers with Urban Indian Organizations before making policies about American Indians. There are no communication chains to any other agencies, including the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

“We must move past the notion that only the IHS has a trust obligation to Native people,” Murillo said. “Because the truth is, the federal government has the responsibility to provide care for all native people.”

The federal government has an obligation to provide health care for American Indians because of treaties signed with tribal nations in exchange for their land.

According to Rep. Melanie Stansbury, D-N.M., Urban American Indians rely on health organizations in major cities, such as the Zuni Clinic in Albuquerque, which offers primary care, dental and behavioral health services at no cost. Grijalva’s bill would bring the Zuni clinic and similar urban organizations into the forefront of decision-making.

The Biden administration’s budget proposal includes a $2.2 billion funding increase for the Indian Health Service, and for the first time, includes an advance appropriation for the IHS so funding does not have to be approved each year. This would protect the IHS from a government shutdown if an annual federal budget is not approved, as nearly happened last week. However, Biden’s budget proposal has yet to be approved by Congress.

Murillo ultimately wants American Indian voices to guide all federal-level public health conversations related to Native Americans.

“We would like to adhere to the phrase ‘no policies about us without us,’” he said.