The cell was cold and stark.

Gray concrete walls enclosed the small area, leaving little room to move. A mattress lay on the hard floor, and a simple desk was fixed to one wall.

A small footlocker held a few of Detroit native Shaka Senghor’s belongings in a corner; across from it, an exposed toilet stood without privacy. The large steel door had a closed shutter, leaving only a small window to glimpse into the prison yard. Senghor said he spent about 23 hours a day there during seven of his 19 years in prison for second-degree murder. The silence of solitary confinement was shattered by toilets flushing, officers beating on cell doors, and the occasional slam of footlockers. The cell felt cramped and claustrophobic,

Senghor said. Measuring six by nine feet, every inch seemed to suffocate hope.

“If I could describe my experience in solitary confinement in three words, it would be ‘trapped in hell,’” said Senghor, now 51 years old, who lives in Los Angeles and is a leading national advocate for reforming severe isolation practices in state and federal prisons.

The experience endured by Senghor and others in state and federal prisons, including one inmate who died five years ago in a northern Michigan prison, has garnered increased scrutiny from some members of Congress, government watchdogs and advocates for incarcerated individuals. The Justice Department’s inspector general has repeatedly warned the federal Bureau of Prisons over the years to avoid the overuse of such isolating

punishment, noting that it does little to limit bad behavior and can lead to more psychological problems.

But union officials for state and federal prison guards argue that restrictive housing is an essential measure for ensuring the safety of both inmates and staff.

“We don’t have the means to just take prisoners who are problematic or who are highly assaulted or who kill people inside prison and just move them to another location if they act out and commit these serious crimes inside,” said Byron Osborn, the president of the Michigan Corrections Organization, who has also been a correctional officer for 29 years. “We have to have a mechanism to separate them from the population. The prison population, just like our regular society, separates them from our public society because they

can’t follow the rules and they’re a danger to others around them.”

But not enough has been done to address a host of reforms, argue lawmakers, former prisoners and government watchdogs. A report led by the Justice Department’s inspector general found that over half of the inmates who died by suicide were being held in single-cell confinement. The Department of Justice’s internal watchdog also recommended that the Bureau of Prisons take steps to ensure inmates with severe mental health conditions were not placed in restrictive housing. “The time for studies is over. The death rate in our prisons is unacceptable. Damage to mental health is unacceptable,” U.S. Sen. Dick Durbin, D-Illinois, chairman of the Senate Judiciary Committee, said at a hearing in February.

Ex-inmates like Senghor argue that, at a minimum, state and federal governments should abolish solitary confinement for inmates with several mental and behavioral health conditions.

“It was one of the most barbaric and inhumane environments that I have ever witnessed,” Senghor said of isolation in Michigan prisons. “They would pepper spray the men in their cells. They would chain them down to their beds. They would deprive us of food.”

The Michigan Department of Corrections could not directly address Senghor’s allegations. But spokesman Kyle Kaminski noted many policies and practices have changed during the past 20 years, including enhanced training, physical condition improvements and a weekly call to family. So it would be “inaccurate and a disservice” to current administrators and prison guards to portray the events of 20 years as happening today, he said.

“Only the amount of force necessary to control a disruptive prisoner may be used, and all uses of force must be documented and reported,” Kaminski said. “Staff are trained to use alternatives to force, but should it become necessary, such as a prisoner refusing to exit their cell or follow staff direction to relinquish a weapon in their cell, the warden or deputy warden can approve a physical cell extraction by trained staff, which may include the use of a non-lethal chemical agent (pepper spray),” he added.

Lawmakers move for changes

Durbin and Delaware Sen. Chris Coons introduced the Solitary Confinement Reform Act last month, seeking to limit its use as a temporary measure, not one that lasts years. Last July, U.S. Rep. Rashida Tlaib, D-Detroit, joined other House lawmakers in introducing the End Solitary Confinement Act.

“Solitary confinement is torture, and torture should have no place in our society,” Tlaib said in a statement.

Rep. Rashida Tlaib (D-Mich.) called solitary confinement “torture.” (Dan Hu/MNS)

Prison reform advocates want to see Michigan and other states follow the federal government’s lead and move away from isolation strategies as a form of punishment.

“We definitely believe that by our Congress passing laws limiting the use of solitary confinement and mandating improved conditions in the higher level settings of prisons should send a message to our Michigan leaders that it’s time for a change,” said Lois Pullano, executive director of Citizens For Prison Reform and the coordinator for the Open MI Door campaign. “Federal laws being made are not going to mandate that out state prisons change

anything. However, I do believe it’s the ripple effect, and it would be a wakeup call for our leaders to begin implementing these same changes within Michigan.”

The federal Bureau of Prisons did not respond to multiple requests for comment. In August 2022, the Biden administration tapped Oregon prisons director Collete Peters to lead the bureau. Attorney General Merrick Garland said Peters was selected in part because she was “instrumental to reforms there, including efforts to prioritize employee health and wellness,modernize custodial practices, and humanize correctional environments.”

Michigan Corrections’ Kaminski said the state prison operator has “continuously worked to reduce the number of individuals in administrative segregation.”

The number of prisoners in administrative segregation has plunged 70% from a daily average population of 1,314 in fiscal year 2008 to 389 today, according to the state Department of Corrections. The overall inmate population has declined 32% from 48,686 at the end of 2008 to 32,986 at the end of 2023, according to the state.

“The department’s expectations for our operations and staff are clear, as we hold ourselves accountable to be an effective and humane department and are seen as a national leader in corrections,” Kaminski said in a statement.

One prisoner’s experience

Senghor said he grew up in an abusive household on Detroit’s east side and ran away when he was just 13 years old.

He had dreams of becoming a doctor, which went down the drain after he got involved with the crack cocaine trade business. Within six months, he became addicted.

Though Senghor was able to break his addiction, he found himself caught up in street culture.

At 17, he was shot multiple times and taken to Sinai Grace Hospital in March 1990. With little treatment for his mental health, Senghor was released from the hospital a few days later with what he believes to be post-traumatic stress disorder. With no access to therapists, Senghor began to carry a handgun with him every day.

In July 1991, Senghor said he shot and killed a man over an escalated fight related to a drug deal he refused to make, leading to his arrest for second-degree murder. Senghor spent 19 years in prison. He said seven of those years were spent in restrictive housing, also known as solitary confinement, after getting into a fight with a correctional officer and being charged with trying to escape prison.

He acknowledged getting into the fight but claims he wasn’t trying to escape. Senghor served his sentence at the Michigan Reformatory in Ionia, Standish Maximum Correctional Facility and the Oaks Correctional Facility in Manistee. Michigan Reformatory and Standish Max have since been shuttered. The longest time Senghor spent in solitary was four and a half years at a time at Oaks Correctional Facility, he said.

“There were instances where they would leave us outside in the cold, far beyond the time that we were supposed to have been outside,” Senghor said. “It was just high levels of mental, physical and psychological abuse.”

The Michigan Department of Corrections has records going back to 1993, which excludes the first two years of Senghor’s imprisonment. He was put in solitary confinement for two major misconduct violations, according to the state, but not for an attempted escape.

In 1994, he was put in administrative segregation “after being found guilty of assaulting another prisoner,” Kaminski said, which resulted in a placement of 2.5 months. In 1999, he was placed in solitary again “after being found guilty of assaulting an employee … and disobeying a direct staff order during that event,” said Kaminski, which resulted in a stint of four years and four months.

“Mr. Senghor was not housed in Administrative Segregation for the final 5-plus years of his sentence, and he was paroled in 2010, meaning his time in segregation occurred roughly 20 years ago,” he added.

International guidelines, notably the Mandela Rules, call for restricting the use of solitary confinement “as a measure of last resort, to be used only in exceptional circumstances” and classify any prolonged isolation exceeding 15 consecutive days as deemed a form of torture.

“We believe this is a critical issue that needs to be addressed here in Michigan,” Pullano said. “There is great harm and trauma that is caused by the use of solitary confinement.”

‘They did nothing’

The Michigan Department of Corrections said it has a policy guaranteeing inmates in solitary confinement have access to health care and mental health support. The Department of Corrections said it reserves solitary confinement for inmates who pose a significant threat to the safety and security of the prison, staff or other inmates, such as prisoners posing significant threats, serious escape risks, proving unable to be managed in the general population or being under investigation for felonious behavior. But inmates may request administrative segregation if they need protection from other inmates.

Hearings are conducted before placing a prisoner in administrative segregation, and ongoing reviews ensure the necessity of continued segregation, with prisoners retaining access to essential services and programs, Kaminski said. If prisoners request solitary confinement for their own protection, they undergo an interview with prison staff, who decide whether to grant the request.

The prevalence of gang activity and violence within prisons underscores the need for restrictive housing units, said Osborn, a correctional officer at the Chippewa Correctional Facility who added there are pervasive issues of extortion, assault and sexual violence that prompt many inmates to voluntarily seek segregation for protection. Both Axford and Osborn estimated that more than half of inmates in solitary confinement request it for

protection.

Michigan’s Kaminski confirmed “a proportion” of the prison population is in administrative segregation because “they refuse to live in general population with other prisoners,” but couldn’t provide a breakdown.

“Some directly request protection from other prisoners, resulting in their placement in temporary segregation so that their protection needs can be investigated, while others refuse to follow staff orders to go to their assigned cells,” he said.

But the overall solitary confinement policy has been questioned in one recent case where a family reported that their loved one went weeks without prescribed medication, even after formally alerting the warden and health care providers.

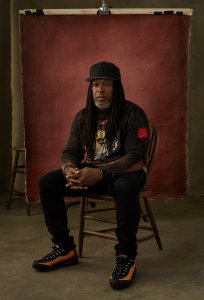

Shaka Senghor spent seven years in solitary confinement. He is now a leading national advocate for reforming severe isolation practices in state and federal prisons. (Courtesy Shaka Senghor)

Danielle Dunn’s brother, Jonathan Lancaster, died in solitary confinement in 2019 at the Alger Correctional Facility in Munising in Michigan’s Upper Peninsula. He was in prison for robbery and gun crimes in Wayne County. Lancaster was transferred to administrative segregation after receiving a misconduct for assaulting another prisoner, according to the Michigan Department of Corrections.

After being placed in solitary confinement in December 2018, in a matter of weeks, Lancaster began experiencing sleep deprivation and struggled with his mental health, Dunn said. According to the Attorney General’s office, Lancaster, stopped consuming food and fluids. He was then confined to an observation cell and restrained until his passing three days later, state prosecutors said.

“He’s having hallucinations. He’s hearing voices. He’s sitting and crouching for hours not moving, you know, he’s not eating. And then they did nothing,” Dunn said. “And did they ever think of removing him from the solitary confinement unit when he started getting mentally ill? Not until the day of his death. And I think at that point they realized it was too far gone.”

Lancaster died in February 2019 from dehydration after losing 51 pounds, or 26% of his body weight, according to a federal lawsuit filed in 2020.

“People walked in and said, ‘You should probably eat or drink something, you know, you could die from that.’ And nobody lifted a finger. Nobody did anything,” Dunn said. Dunn blames correctional officers for not providing him with the care he needed until after his death.

“The MDOC’s internal investigation in that case focused on if the actions of individual employees were consistent with applicable policies and procedures. That investigation found that certain employees did not comply with policy and procedure,” Kaminski said. “These employees were disciplined and, in several cases, discharged.”

Last June, the Attorney General’s office charged six former MDOC employees with involuntary manslaughter in Lancaster’s death, including the acting warden and one of his deputies at the time. Dunn said the criminal charges came after she spent more than four years trying to contact MDOC officials about her brother’s death in solitary confinement, including Director Heidi Washington.

“How do we allow this to keep happening? And then Heidi Washington looks people in the face and says we have the best facilities in the country,” Dunn remarked. “How does that continue to happen?”

A decade without action

According to the U.S. Government Accountability Office, there are three types of restrictive housing. The special housing unit (SHU) and special management unit (SMU) are units separated from the general prison population where inmates are housed either alone or with another prisoner.

The administrative maximum facility (ADX) is used for long-term housing for those classified as the highest security risks in prison who pose severe threats to the staff and prison population. The purpose of restrictive housing is to separate incarcerated individuals from the general population to “protect the safety, security and orderly operation of facilities,” according to the Department of Justice.

A report from February from the GAO, Congress’s investigative arm, accuses the Bureau of Prisons of failing to enact crucial recommendations.

“A number of these recommendations are a decade old. It’s been a while,” said Gretta Goodwin, the director of GAO’s Homeland Security and Justice team. “When we looked at the 87 recommendations, the majority of them — about 54 — still required some kind of action.”

These recommendations cover various measures, including the need for specific policies to determine the conditions under which individuals are placed in restrictive housing and address concerns about the mental and physical health of those in isolation.

According to the Department of Justice, 344 inmates in solitary confinement died by suicide, homicide or other unnatural causes between 2014 and 2021.

Single-cell housing also has proven to increase the risk of suicide, as noted by high-profile deaths at federal prisons, such as Jeffrey Epstein’s suicide in 2019. Investigations after Epstein’s death found that staff failed to take measures to ensure inmates in restrictive housing were safe, such as conducting inmate counts and 30-minute rounds; searching inmate cells; ensuring adequate supervision of the housing unit; and checking that the

security cameras are functioning.

Peters, the director of the Bureau of Prisons, said at the Feb. 28 Senate hearing that 1 in 3 inmates have symptoms of PTSD, which lead to more anxiety, depression, and reliance on substance abuse.

The federal agency blamed a lack of government funding for the shortage of staffing and resources but pledged they had plans to approve a new policy to reduce the time inmates spend in restrictive housing.

Most prisons have shortages of trained mental health staff and resources. Jean Casella, director of Solitary Watch, a nonprofit prison watchdog organization, said in an interview that regardless of having a previous mental illness, prisoners who are subject to the kind of isolation they face in solitary confinement are proven to come out with cognitive side effects.

“I think mental health is basically incompatible with solitary confinement,” Casella said. Adding to the urgency, a GAO memo underscores that, as of October, about 12,000 individuals, or 8% of the federal prison population, reside in restrictive housing cells.

The GAO study also emphasizes that the BOP “recognizes that restrictive housing is not an effective deterrent for bad behavior and can even increase future misconduct.”

Still, the bureau has made slow progress in addressing the recommendations.

“We have housing reforms underway now that will reduce the amount of time adults in custody spend in restrictive housing,” Peters told lawmakers concerned about this issue. Brandy Moore-White, president of the American Federation of Government Employees Council representing the Bureau of Prisons workers, said the bureau tries to restrict the isolation of individuals who are known to have mental health conditions.

“The special housing unit, when used correctly, is a tool. Could those tools be improved? Absolutely,” Moore-White said. “But it absolutely is a tool that, if removed, the prison system in itself will suffer drastically.”

William Axford, the north central regional vice president of the American Federation of Government Employees Council representing the Bureau of Prisons workers who has previously worked as a federal correctional officer, said he found in his experience that solitary confinement is not inhumane.

“The people that say that being in these lockdown units is inhumane. I used to work the lockdown unit a lot when I was an officer. I can only speak to my experiences, but I don’t see anything inhumane about it,” said Axford, a former correctional officer at Federal Medical Center Rochester, a federal prison in Minnesota specializing in medical and mental health care.

“Now, is it a place that I would want to be? Absolutely not. But it’s not like we’re just snatching up inmates off the compound and throwing them in there willingly. You basically have to earn your way in there by doing something pretty bad.”

From solitary to advocacy

For Senghor, looking for mental health support was a harsh reality he encountered during his time in solitary confinement. Being one of the few literate people behind bars, Senghor said he overcame mental challenges by reading books that helped him understand what was happening inside of him.

“The level of mental health challenges in there were extremely high,” Senghor said. “We had men who would cut themselves with whatever they could get their hands on. There was one man who set himself on fire. There were constant wars going on between the men serving time and the officers.”

Throughout his 19-year sentence, Senghor said he turned to reading, journaling and meditation to reconcile with his past crimes.

Upon his release in 2010, he emerged as an advocate for reform and wrote a book, “Writing My Wrongs,” which tells the story of his transformation from childhood to incarceration and how he became an activist. He is now writing his third book and delivering speeches around the world.

“I believe that when you see people suffering,” Senghor said, “you have a responsibility to

speak out.”