A vivid example of Washington’s rank as having the highest number of homeless people per capita is the line of pitched tents outside the brick walls of Union Station. Any free sidewalk space is occupied by shopping carts overflowing with blankets and cardboard boxes. Some contain granola bars while others are filled with extra socks. Several of the homeless people crouched along the wall are talking to themselves. Others yell at nobody in particular, their expletives occasionally drowned out by the blaring horn of a passing train.

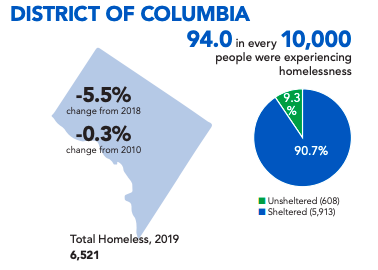

D.C. has a higher rate of homelessness per capita than any state in America at 94 per 10,000 residents, according to a Department of Housing and Urban Development report in January. The city’s ratio is more than twice the rate of New York state (46) and California (38) and more than five times the national average.

The District of Columbia’s Department of Behavioral Health is trying to escape this unwanted first-place title. Their Community Response Team works 24/7 providing care to the city’s homeless individuals suffering from mental illnesses.

Director Anthony Hall leads the 52-person team consisting of licensed clinicians and individuals with expertise in homelessness, mental health and substance use, crisis intervention and the criminal justice system.

“We’ll go out, assess the situation, conduct an evaluation and make a determination for care,” Hall said.

The team frequently conducts checks in “hot spots” such as the area around Union Station or parts of Columbia Heights to ensure individuals previously cared for are being proactive with their services.

“We see a lot of acutely psychotic individuals not currently undergoing treatment who lack the insight to understand, despite the fact that it might not be intentional, that their behaviors put them at risk or cause them to appear threatening to another person,” said Hall.

According to the Metropolitan Washington Council of Governments, 25% of people experiencing homelessness in the District of Columbia suffer from some form of severe mental illness compared with 4% of the general overall population. These illnesses include anxiety, depression, psychosis, schizophrenia and bipolar disorder.

Hall said he has seen signs the team’s work has started to take root. Recently he received a call from a homeless patient asking him for help.

Department of Behavioral Health Director Barbara Bazron said her agency provides treatment for anyone within the District needing mental health or substance use disorder services regardless of their ability to pay.

“We provide whatever it takes wherever necessary to make a difference in the life of that person,” Bazron said.

The DBH budget was $285 million in 2019, a $7 million increase from 2018, to help treat homeless persons. The department served 24,098 mental health consumers, an increase from 23,259 in 2018. Last year, it cost $5,062 to treat a mentally ill patient—the highest price recorded by the department. Bazron said the increase was due to hiring more intensive care experts. The DBH now has over 80 certified community-based providers who are responsible for distributing medications to individuals needing care or any continued treatment.

“D.C. is a pretty small, compact place so people tend to find their spot and those who are serving them kind of know where those spots happen to be,” Bazron said.

Her department, especially the Community Response Team, works closely with the Metropolitan Police Department officers who respond to calls regarding mentally ill homeless persons, often in situations when there are complaints of threatening or disturbing members of the public.

“We have a community intervention officer program in partnership with the MPD and the Department of Homeland Security that trains officers in mental health strategies and support,” Bazron said.

Officers learn de-escalation techniques and how to identify key characteristics of individuals with mental health issues.

“If an officer feels that person might have a mental health problem, then they will correspond with our team or transport them to our crisis psychiatric emergency treatment program,” Bazron said.

The DBH is currently housing 2,200 homeless persons with mental health issues in community residential facilities.

“The goal is to get and keep people in treatment so they can be on the pathway to recovery and ultimately, as our mayor says, the pathway to the middle class,” Bazron said.

Metal grates and train tracks act as the night sky for D.C. residents living in the M St NE underpass. (Angelina Campanile/MNS)

Last year, Mayor Muriel Bowser announced her goal to create 36,000 affordable housing units by 2025— housing that could help homeless residents find shelter and make D.C. more affordable for working-class residents affected by high rents and gentrification.

Until the development of more tangible long-term solutions, Bazron and Hall continue to develop their team and care for those needing treatment in the nation’s capital.

“I would like to see us expand and improve our community footprint,” said Hall. “That’s been the goal—to really integrate behavioral health services into the everyday experience of the residents of the District so that it’s easy to access information about services and treatment in the community.