WASHINGTON — Since President Donald Trump’s return to the White House, his administration cleared the military of most of its top female-ranking officers, disappointing many women veterans and active duty personnel.

Though Trump touted his plans to flush out military leadership during his campaign trail, the latest overhaul seems to have struck a different tone.

Following a series of high-profile departures, the U.S. military was without a single woman in a four-star general or admiral leadership position.

Trump’s actions have since raised serious questions from women veterans and service members about whether his administration’s trademark campaign on abolishing DEI initiatives played a role. And on top of that, some members of the military have begun to express concern about whether the firings could signal a growing vacuum of support for its female officers.

“I wish people would think about their mothers, ‘Are you really saying that this person who bore you is incapable of leading you?’” said Sgt. Maj. Pamela Wilson, an Army veteran who served for nearly 35 years.

String of firings

The departures began when Linda Fagan, the first female to lead the Coast Guard, was fired on Trump’s first day back in office. Officials cited reasons such as failure to address border security and “excessive focus on diversity, equity, and inclusion policies” for her dismissal, according to CNN.

Fagan’s firing immediately drew outcry from fellow veterans, including Sen. Tammy Duckworth (D-Ill.), who worked with her.

From the start, Senators lauded her as a good pick for Coast Guard commandment after giving her unanimous support during her Senate confirmation hearing in 2022.

After she was fired, Duckworth, an Iraq War veteran and Purple Heart recipient, wrote on her X account that Fagan was “more qualified to serve in her role than Pete Hegseth is to be Defense Secretary.” She added that “Trump would rather appear ‘anti-woke’ than keep our military strong.”

During Fagan’s 37-year career, she served on all seven continents, including in high-ranking roles like Pacific Area Commander, District and Sector Commanders and Marine Inspector.

However, at times, Fagan’s tenure was mired by complaints about the agency’s response to problems of sexual assault and harassment.

Despite calling out Fagan over those issues at public hearings, Sen. Richard Blumenthal (D-Conn.), said in a statement that Fagan’s firing still “raises concerns about how Donald Trump intends to treat professional, dedicated military men and women who have faithfully served our country for decades.”

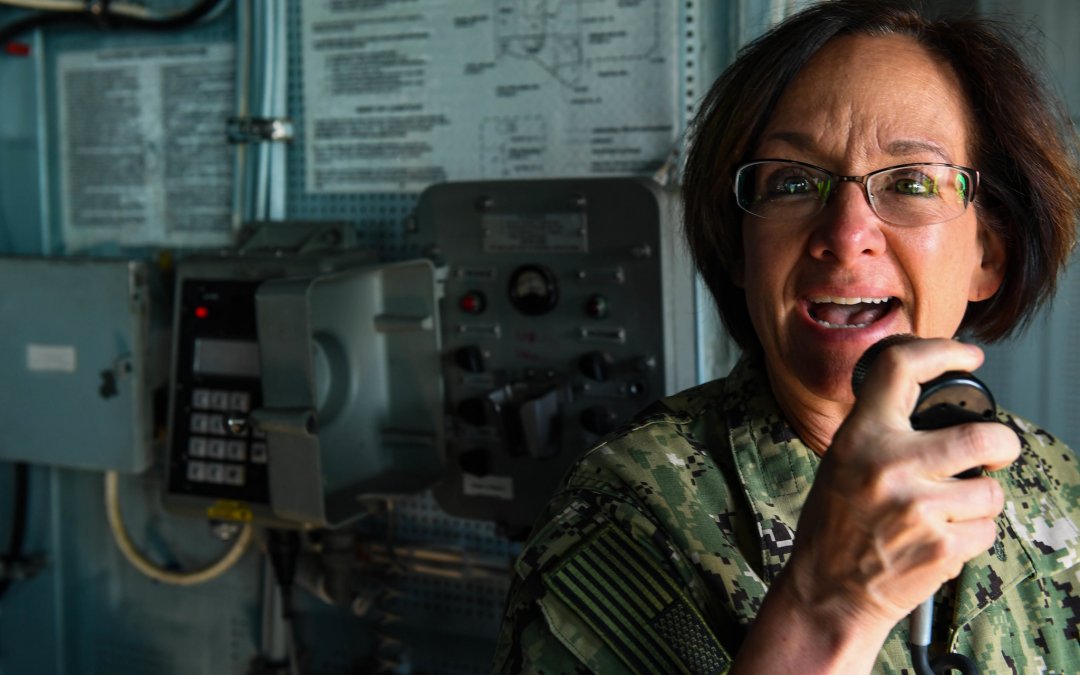

Weeks later, Lisa Franchetti, the first female Chief of Naval Operations, was next to follow. Before then, Franchetti spent almost 20 years commanding various fleets, including the destroyer U.S.S. Ross, two aircraft carrier strike groups and naval forces in Korea.

Hegseth, who ordered Franchetti’s firing, did not provide a specific reason for the decision.

Hegseth’s decision came after he faced scrutiny during his Senate confirmation hearing in January for his past comments suggesting women should not serve in combat roles in the army.

“Why should women in our military, if you were the secretary of defense, believe that they would have a fair shot and an equal opportunity to rise through the ranks if, on the one hand, you say that women are not competent, they make our military less effective,” Sen. Jeanne Shaheen (D – N.H.) pressed Hegseth during the hearing.

Most recently, Hegeth also dismissed his Senior Military Advisor Jennifer Short. A former C-130E navigator and an A-10 pilot, Short served in the role for less than a year.

Then came Telita Crosland, former head of the military’s Defense Health Agency, who was forced to retire by the Pentagon after a 32-year career.

“We were making progress”

In past transitions, those who served in the same high-ranking positions as Franchetti or Fagan usually lasted under multiple administrations until the end of their posts, experts said.

Many veterans, including Rep. Mikie Sherrill (D – N.J.), called these firings an affront to qualified female officers.

Last month, Sherrill wrote on her X account that Hegseth and others “are relegating women to second class citizens in our military, taking competent and qualified individuals out of important leadership posts in our armed forces.”

Before running for office, Sherrill served on active duty nine years as a helicopter pilot in the Navy, during which she met Franchetti at the Atlantic Fleet Headquarters in Norfolk, Virginia.

At a February town hall meeting in Monmouth County, New Jersey, she told a buzzing crowd that she was “so happy” to find out about Franchetti’s appointment months ago. She commended Franchetti as a top leader and trailblazer in the military.

“It would have been imaginable to me as a midshipman that we would have a woman in that role,” said Sherrill, while donning her Navy bomber jacket. “I was feeling like we were making progress here.”

The firings have also drawn sympathies from other veterans, who fear that the current situation might not be a one-off.

Wilson served 32 years as a religious affairs specialist and active duty in the military starting in 1985, the same year when Fagan also entered the Coast Guard.

“I can only imagine what’s going on in (Fagan’s) head, we’re hurting the wrong people,” Wilson said in an interview. “What is the metric that’s even being used? They haven’t been negligent in their duties.”

During the Iraq War, Wilson served as one of the few top female leaders in the operation.

She helmed a multinational unit of forces, directing them to provide religious support and guidance to the rest of the soldiers. After she retired, Wilson became the first female appointed as Honorary Sergeant Major of the Chaplain Corps in 2019.

She said these recent firings not only were “low blows” from the Trump administration but also fears they draw up a polarizing future for female officers.

Some women service members recalled the time when females serving in the military were a rarity.

Constance Edwards was 22 when she enlisted in the Army Student Nurse Cadet Corp. She was later deployed with the Army for a year during the Vietnam War, when most serving women were nurses then.

During her 33 years in the U.S. Army Reserve Nurse Corps, Edwards was appointed as a Colonel, the highest rank within the military branch’s Nurse Corps.

Edwards called the firings of recent military female leaders as the Trump administration’s “pure ignorance” and that they possibly reaffirm the military’s tradition of being male-dominated.

“They didn’t figure out whether these people were not doing what they were necessary,” Edwards said. We needed females into the military in top administration, because the military was set up for men.”

Lack of female military leaders today

In recent years, female enlistment in the U.S. military has continued to grow. In 2023, women made up 17.5% of active-duty military personnel. Women today serve in all branches of the military, including combat roles.

A recurring problem, however, has been the military’s struggles to recruit and retain women service members.

According to a 2020 Government Accountability Office study, women were 28% more likely to withdraw than men. Studies also found that gender discrimination and sexual harassment have remained prevalent for female officers.

Women did not officially serve until June 1948, when President Harry S. Truman signed the Women’s Armed Service Integration Act allowing women to receive regular permanent status in the armed forces.

Rochelle Crump was among the thousands who served in the Women’s Army Corps, the sole women’s branch of the U.S. Army before it was merged with the male units in 1978. At 17, she joined her unit in 1971 near the height of the Vietnam War.

Crump was never deployed overseas but served tours in military forts across California, Alabama and Georgia. Seeing other young female officers around her at the time, she said, provided her a deeper sense of “can do” in the military.

Today, when women are still in the minority in the Army, they need to see that representation from leadership, Crump said.

“Those women will need that leadership, they need to see that leadership, they need to know they can do those things those officers can do now,” Crump, who serves as the president of the National Women Veterans United in Chicago, Illinois.

Crump added that the Trump administration’s recent dismissal of female military officials has been “a backwards situation that’s been coming a long time.”

“ It was not because of DEI they earned it,” Crump said. “They worked hard for it and they deserve to have been in those positions.”