WASHINGTON – Senators on Wednesday heard from companies and nonprofit groups on effective ways to have producers take responsibility for packaging waste and other sustainability goals as they weigh legislation to curb pollution from plastics and disposable items.

The concept of putting the onus on manufacturers, known as extended producer responsibility (EPR), is explained by the Sustainable Packaging Coalition as requiring producers “to provide funding and/or services that assist in managing covered products after the use phase.”

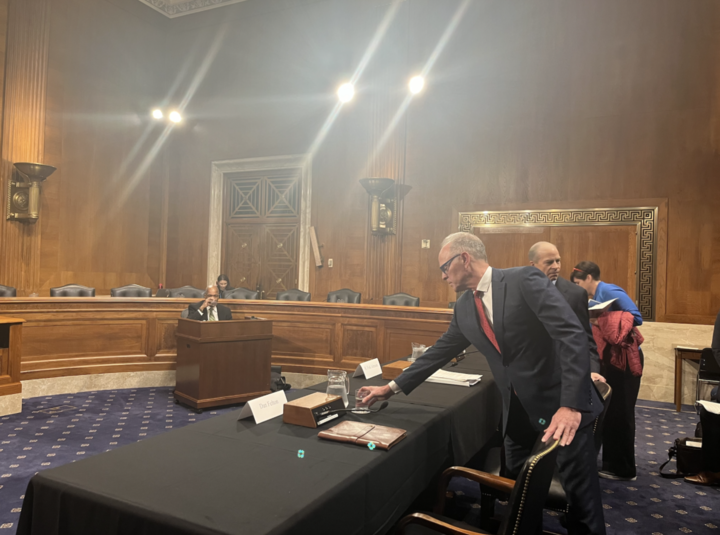

The ranking member of the Senate Environment and Public Works Committee, Sen. Shelley Moore Capito (R-W.Va.), said in her opening statement that she wanted to ensure that policies being considered “are grounded in reality.”

Herbert Fisk Johnson III, the chairman and CEO of S.C. Johnson & Son, which makes numerous consumer cleaning and household products like Windex and Ziploc, said he is a longtime conservationist who still sees the value of plastic as a versatile and cost-effective product. He also backs EPR initiatives.

“The challenge is reconciling those two perspectives,” Johnson said. He aims to “preserve many of the benefits that plastic has brought to humanity, while preventing the vast amounts of plastic that end up in landfills, or even worse, end up in the environment.”

Sen. Pete Ricketts (R-Neb.) said he worried that the extra costs would potentially fall on low-income households, citing how there are various instances where regulation has raised costs for consumers.

Dan Felton, the executive director of AMERIPEN, a group that represents the North American packaging industry, pushed back and said the United States would see the best impact if producers absorbed some of the extra costs and kept prices the same.

“Packaging has value throughout its life cycle, and none of it belongs in roadways, waterways, or landfills,” Felton said.

Sen. Alex Padilla (D-Calif.) added that EPR is “just one aspect of the circular economy for plastic” and that lawmakers should also look at initiatives like recycling infrastructure investments, improved data collection and any other strategies.

EPR exists in some capacity in only a handful of states. According to the Sustainable Packaging Coalition, while nine states have introduced legislation involving EPR for packaging in 2024, just four of those bills have passed: in Maine, California, Oregon and Colorado.

Producers said they are facing barriers as a result of inconsistent state regulations. For example, Johnson’s company finds it difficult to comply when his packaging is shipped across state lines.

“The labeling law that’s part of EPR in California will prevent the chasing arrows symbol in most cases, whereas 30 other states have laws that mandate the chasing arrows,” Johnson said. “It would be impossible for us to comply with the law when you have that kind of labeling conflict.”

Federal standards would help address those inconsistencies, some witnesses said. Erin Simon, who used to work for the plastics industry but is now the vice president of plastic waste and business at the World Wildlife Fund, expressed frustration with the lack of federal action regarding single-use plastics.

“We can’t even get our small recycling bills through Congress, so how in the world are we going to be able to do something on a federal level at the scale that we’re talking about here?” Simon asked.

Johnson urged the senators to pass these regulations as soon as possible, saying there are benefits to early implementation that give the government more room to adjust policy over time.

“The sooner we get federal regulation and the more time given to meet goals, the more innovation can happen, the more you get economies of scale and you can mitigate the costs and inconvenience to the people that buy our products,” he said.

Simon also backed Johnson’s sentiment to move quickly.

This is a “huge untapped opportunity,” she said. “If we were to start today to transform our plastic linear economy into a circular one, we could save more than $4 trillion in direct environmental and social costs by 2040.”