WASHINGTON – Lawmakers tried to identify better ways of enforcing laws to combat the imports of goods made with slave labor and called on U.S. Customs and Border Protection officials to suggest how to improve tracking of goods that violate the Uyghur Forced Labor Prevention Act on Thursday.

The U.S. has been especially concerned about goods made in China in the Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region, home to the Uyghur people, a predominantly Muslim ethnic group. Over the past few years, the Chinese government has detained Uyghurs in internment camps, forcibly sterilized Uyghur women, forced the population to work in poor labor conditions for little to no pay and attempted to destroy Uyghur culture.

The Uyghur Forced Labor Prevention Act earned bipartisan support in Congress and was signed into law by President Joe Biden in Dec. 2021.

However, CBP has struggled to identify and prohibit shipments containing forced labor products in part because shippers are taking advantage of “de minimis” rules, which allow shipments worth less than $800 to enter the U.S. free of some inspections and taxes.

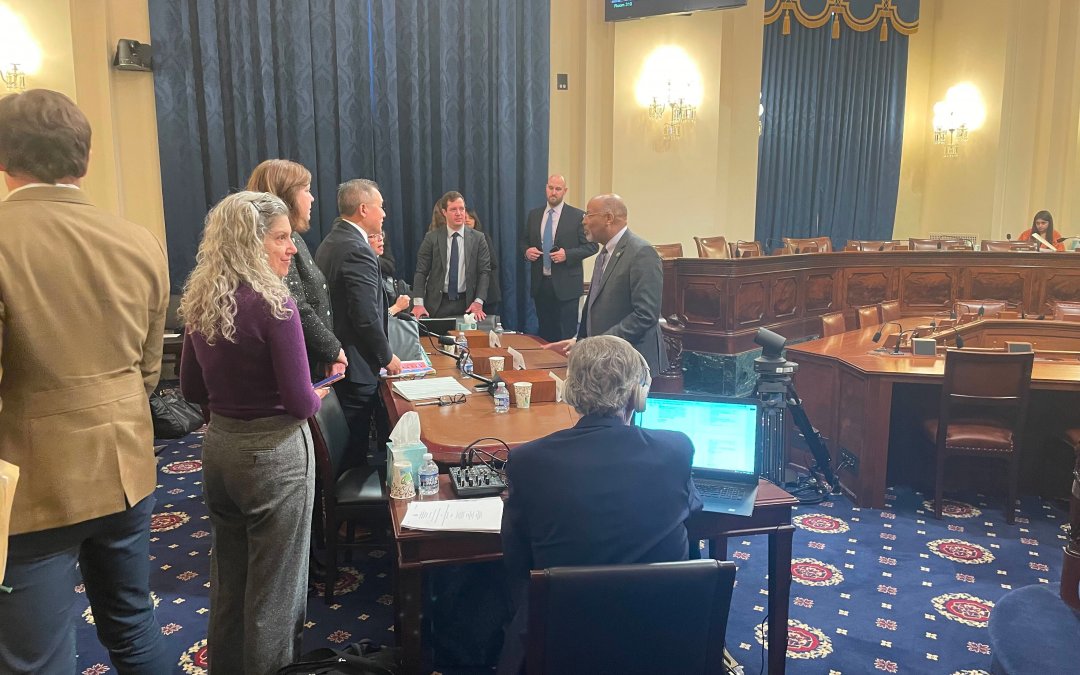

“Unfortunately, China’s use of forced labor in global supply chains continues to pose a significant enforcement challenge across a wide range of economic sectors, including textiles, minerals, and seafood,” said Rep. Dan Bishop (R-N.C.), chair of the House Homeland Security Subcommittee on Oversight, Investigations, and Accountability, which sponsored a hearing on the issue on Thursday.

The subcommittee had also held a hearing on the matter on Oct. 19, where experts pointed out that de minimis rules were not preventing such imports.

Christa Brzozowski, an acting assistant secretary at the Department of Homeland Security, said Thursday that her agency shared the lawmakers’ concerns about de minimis shipments.

“We do our best with information that we do have,” Brzozowski said. “Over the longer term, we would be open to a conversation with Congress.”

Furthermore, the CBP has yet to use widespread “isotopic testing” – which uses DNA to identify where certain goods like cotton fiber are from – to identify goods sourced from Xinjiang. “It is not clear how widely or routinely such forensic technologies are being used,” Bishop said.

Michael Stumo, CEO of the Coalition for a Prosperous America and witness at the Oct. 19 hearing, said that some rapidly rising “fast-fashion” Chinese brands like Shein and Temu are continuing to export goods to the U.S. despite the Uyghur law. To Stumo, the de minimis loophole is “ungovernable lawlessness.”

Eric Choy, executive director of trade remedy law enforcement at the CBP’s Office of Trade, said Thursday that CBP has created one new isotopic testing lab and plans to use resources from Congress to create two additional labs in order to increase testing.

On top of these challenges, Bishop and Rep. Glenn Ivey (D-Md.), said they were also worried that the laws aren’t doing enough to deter China from using forced labor in the Xinjiang region.

According to Choy, when CBP identifies goods produced by forced labor, the agency denies the shipments’ entry into the U.S. However, even when CBP detains the shipments, the importer is often given the opportunity to re-export their shipments, essentially rerouting products made by forced and child labor.

“My perspective is if we really want to put sanctions in place to punish these companies that are involved in the supply chain and we’ve effectively traced back to forced labor or child labor, allowing them to send [goods] to Plan B for the same amount of money doesn’t seem to really get the message across,” Ivey said.