WASHINGTON — The COVID-19 pandemic has illustrated the government’s failure to adequately prepare for biological threats, experts told senators Thursday at a hearing on improving U.S. biosecurity preparedness.

“Biodefense is too fragmented and uncoordinated across all levels of government, and the private sector too,” Christopher Currie, who directs the Government Accountability Office’s Homeland Security and Justice Team, told members of the Committee on Homeland Security and Governmental Affairs.

“Unfortunately, COVID-19 shows that these gaps were real,” Currie said.

The government’s National Biodefense Strategy, unveiled in 2018, would have helped the United States to prepare for viruses like COVID-19, but the pandemic hit before it could be fully implemented, Currie said.

“Emerging infectious diseases over the last 20 years have occurred with increased frequency,” Gerald Parker, associate dean for Global One Health at Texas A&M University and chair of the National Science Advisory Board for Biosecurity, said before the hearing.

“We dodged a few close calls — but COVID got us,” Parker said.

Similar to traditional weapons of war, infectious biological agents like bacteria and viruses can be used to kill humans, animals and plants. For example, after the terrorist attacks of Sept. 11, 2001, letters laced with anthrax killed five Americans and infected 17 others.

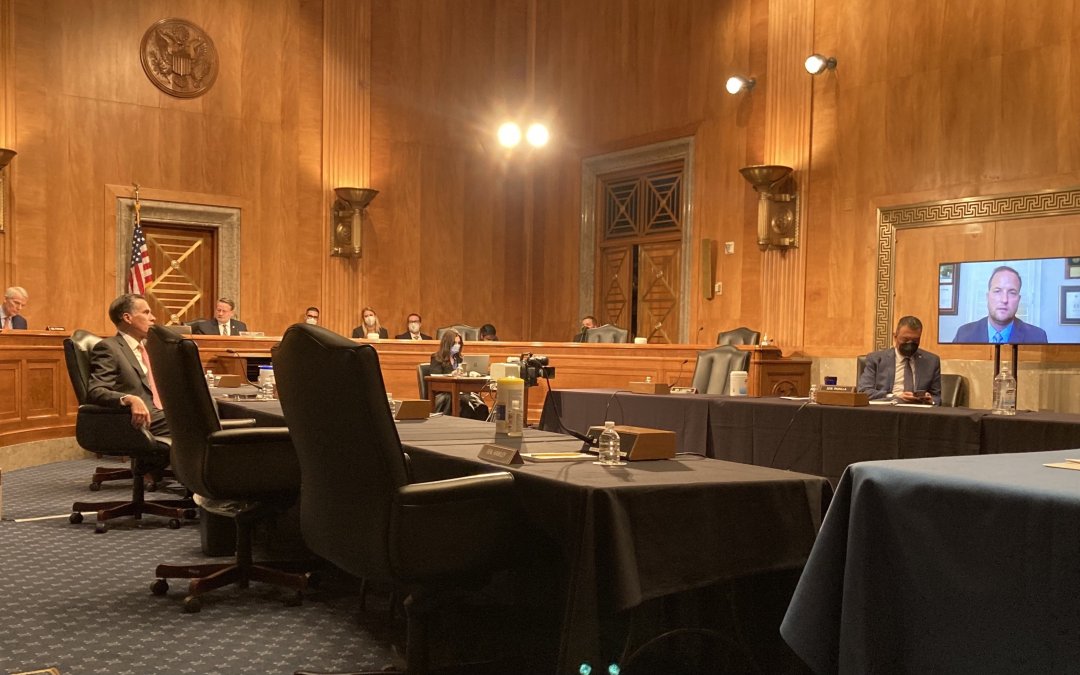

“We have seen how naturally occurring biological threats, such as the virus that causes COVID-19, can significantly harm communities that were not adequately prepared,” said Chairman Gary Peters, D-Mich.

Ranking member Rob Portman, R-Ohio, asked Currie why the United States didn’t catch COVID-19 until January 2020.

“Multiple agencies involved tried to pursue their own surveillance,” Currie responded. “Part of the problem is the fragmentation and lack of integration.”

Currie said his office created new surveillance systems to monitor COVID-19 at the local level and in the private sector.

“We need to look at what we created there and not just get rid of it when COVID’s over,” he said. “We need to use that to develop new surveillance systems.”

Government technologies must be updated so that biological weapons can be detected and mitigated quicker, said Asha George, executive director of Bipartisan Commission on Biodefense.

The Department of Homeland Security’s existing BioWatch Program, which provides biosecurity risk assessment, needs to be replaced, according to George, whose commission released a report in October that found the $80 million-a-year program has questionable accuracy and delayed reporting times.

“There’s no reason to just keep this limping along the way it is,” George said. “We should shut down that program and replace it with applied technology.”

Looking beyond the pandemic, Russia and North Korea’s possession of active biological weapons could pose the next threat, officials said.

“While some strides have been made, we are not sufficiently prepared,” George said.