WASHINGTON — After serving a total of 12 years in prison on a series of felony convictions, Dolfinette Martin spent the first year of her release living in her mother’s senior living apartment, hiding from others in the building because the lease prohibited roommates.

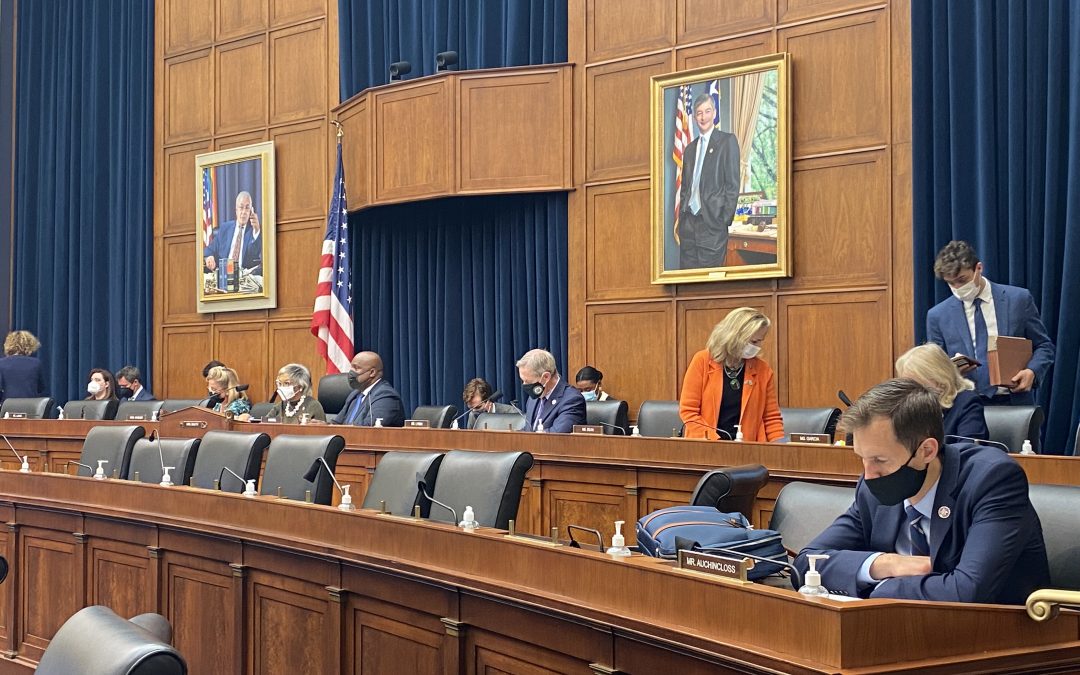

Nearly a decade later, Martin now is the housing director for the New Orleans nonprofit Operation Restoration, and on Tuesday she urged members of the House Financial Services Subcommittee on Diversity and Inclusion to approve legislation that would expand housing, employment and financial opportunities for people who have been incarcerated.

The hearing was part of a continuing effort by Democrats who want to reform the criminal justice system.

Nearly one in three U.S. adults has a prior arrest record or conviction, according to the National Employment Law Project.

“These are our neighbors, our friends, our family members,” Chairwoman Joyce Beatty, D-Ohio, said. “We are a nation of second chances.”

While the U.S. has a record-setting 10 million job openings, more than 8 million people are still unemployed, sometimes due criminal records that are barriers to employment, said Rep. Ann Wagner of Missouri, the top Republican on the subcommittee.

The subcommittee considered four bills — two that would remove barriers to housing and two that would increase economic opportunities for those who have been arrested, convicted or incarcerated.

The Fair Chance at Housing Act would ensure public housing agencies could only deny tenants a home based on criminal activity if they were engaged in “covered criminal conduct” — a felony conviction that threatens the health and safety of other tenants.

The subcommittee also considered legislation that would restrict tenant-screening companies from accessing anything other than conviction records.

Melissa Sorenson, executive director of the Professional Background Screening Association, told the subcommittee the legislation should also include liability protections for employers in case an employee with a criminal record were to harm someone on the job. Sorenson also recommended a uniform “ban-the-box” standard for private employers, which would prohibit them from requesting a job applicant’s criminal record until after conditionally offering the job. Many employers ask job seekers to check a box on an employment application if they have been convicted of a crime. Advocates for eliminating that box say it would help reduce bias in the hiring process.

Starting in December, federal agencies and contractors will be prohibited from requesting a job applicant’s criminal record until after conditionally offering the job.

Sorenson noted that states have differing laws – or no laws – prohibiting “ban-the-box” practices for private employers, which means applicants applying for the same job in different states may receive different treatment.

Other legislation considered during the hearing included the Expanding Opportunities in Banking Act, which would loosen economic restrictions for people who have kept a clean record five years after incarceration, are under 21 or whose records were expunged or who committed minor crimes, like the use of a fake ID or shoplifting.

Financial Services Committee Chairwoman Maxine Waters, D-Calif., said she expects the committee “to be in the forefront of getting rid of these discriminatory policies.”

The measures have yet to be introduced formally in the House.