WASHINGTON – After months of uncertainty, President Donald Trump signed a federal spending bill for the 2019 fiscal year last week. A renewal for the Violence Against Women Act, which expired in September, wasn’t included. But even though the law has ended, funding for its programs continues.

When the news reached Cindy Southworth, executive vice president of the National Network to End Domestic Violence, a social change organization, she was unfazed.

“The expiration is not ideal, but it’s not the worst,” she said.

The Violence Against Women Act provides billions of federal dollars for the investigation and prosecution of violent crimes against women and programs that support domestic violence survivors such as legal aid. Last year, the funding level was $492 million.

When then President Bill Clinton signed the act in 1994, it required a mandatory five-year renewal process, which is not uncommon.

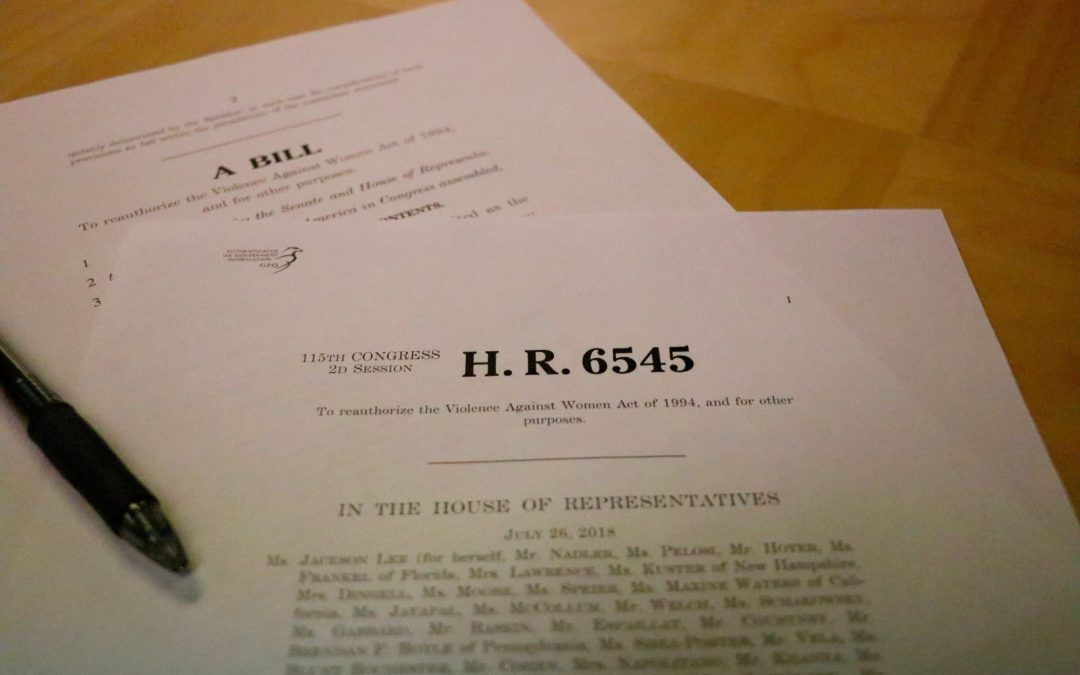

The most recent renewal bill, introduced in 2018, had broad Democratic support but failed to nab a single Republican co-sponsor by the expiration deadline on Sept. 30. Congress extended the law to Dec. 7 and then to Dec. 21 as part of a government funding deal. On Dec. 22, Trump announced a partial government shutdown, further stalling VAWA’s reauthorization.

Democrats were unsuccessful in their attempt to include VAWA in the 2019 appropriations bill signed on Feb. 15.

“They’re using VAWA as political football,” said Dawn Dalton, policy director for the D.C. Coalition Against Domestic Violence, of partisanship that has grown more intense around women’s issues.

Although a reauthorization bill has yet to be introduced in the 116thCongress, some Democrats are working to draft a new version.

“We will be working to strengthen VAWA so it becomes more meaningful and effective for more communities,” said Rep. Deb Haaland, D-Ariz., a supporter of VAWA and one of two indigenous women to be elected to Congress.

“I will be working with my colleagues to update provisions that are particularly important for tribal communities who will benefit from added protections for children, tribal officers, and missing and murdered Native women,” she said.

Dalton said the reauthorization “forces jurisdictions across the country to collaborate” and pressures lawmakers to initiate change by “holding their feet to the fire.”

The National Task Force to End Sexual and Domestic Violence, along with other advocacy groups, said it uses the renewal periods to collaborate with Congress and improve VAWA to ensure its continued efficiency.

For instance, during the previous reauthorization in 2013, lawmakers expanded VAWA’s scope to meet the needs of immigrant and disabled victims, who had not been included in the bill before and sometimes require additional support.

For Task Force leader Qudsia Raja, this is an opportunity to connect lawmakers with the individuals directly affected by the policy they are writing.

“We provide expertise and recommendations from the field, what we hear from survivors and the emerging trends survivors face, that is all information that we bring to The Hill and to members of Congress,” she said.

Raja and others are advocating for increased protection for Native American women and violence survivors living in federally subsidized housing.

At the National Network to End Domestic Violence, Southworth has modest goals for the 2019 reauthorization.

“We try to add inclusions, clarifications and protect every victim possible,” she said. “At a bare minimum, we don’t want any rollbacks. When the bill is reauthorized, we as a movement stand strong that we want Congress, at a minimum, to reauthorize it as it is.”

Despite VAWA’s expiration, it will continue to receive government funding throughout the current fiscal year, which has been the case during every VAWA temporary expiration, including one that lasted from 2011 to 2013.