WASHINGTON – An integrity unit in the Harris County district attorney’s office, which identifies and corrects false convictions, is responsible for 76 total overturned drug convictions dating back to mid-2014, according to the National Registry of Exonerations.

In all 76 of the drug-related exonerations, the suspects pleaded guilty to crimes they did not commit.

The surprising number of reversed convictions in Harris County stems from a lucky tip, said Inger Chandler chief of the Harris County Conviction Review Section, the integrity unit.

In March of 2014, Chandler was contacted by a reporter at the Austin American Statesman who asked about a growing number of drug-related convictions being overturned in Texas after forensic labs got around to testing evidence.

Fortunately for Chandler, the controlled substance division of Houston Forensic Science Center, which tests most DNA evidence and drug evidence for the Houston Police Department, held onto all evidence until it was tested.

The lab was testing evidence that looked like illegal drugs, but the results showed that the substances were not controlled (that is, not illegal), said James Miller, who has managed the controlled substances section for over 25 years.

It’s not unusual for a case to have a substance come up positive in a field test but turn out negative when stronger technology is applied in a traditional lab, said Ramit Plushnick-Masti, public information officer at the Houston Forensic Science Center.

Take Eric Polk for example: When he was 27 years-old in August of 2014, he was arrested in Harris County after police seized a powdery substance that field-tested positive for ecstasy. He was convicted and sentenced to six months in Texas State jail. Two months later, the crime lab tested the evidence and determined the stuff wasn’t ecstasy. Charges against Polk were dismissed in January of 2015.

Catching up with testing the suspected drug evidence of people who pleaded guilty took a long time because the controlled substance section had a backlog going to 2005, Miller said.

The number of wrongful guilty-plea cases in the backlog was around 400. Chandler, alarmed, brought the issue to her unit’s attention to expedite the process.

The lab’s resources were “insufficient to process all of the evidence that was being seized and then requested for testing because, again, we were testing everything at that time,” Miller said.

A 2013 survey conducted by the Justice Department and Drug Enforcement Agency found that 80 percent of drug chemistry sections in state and local crime labs do not analyze all of the cases submitted. Of those labs responding to the survey, 62 percent cited guilty pleas or plea bargains as one of the most common reasons for not checking evidence.

“If the crime lab realized that the defendant plead guilty, they took that evidence and put it at the back of the line because they had so many other pending cases that were more urgent at that point,” Inger Chandler said in a telephone interview from Houston.

In Harris County, the steps required to overturn a wrongful conviction made the process more difficult.

“We had like five or six major decision points in that flow chart where, just truly by human error, we could get behind,” Chandler said. “So we streamlined the process and now all of the ‘no controlled substance’ cases come through us.”

In 2015, a full decade after the backlog began, the lab finished testing all of the cases, James Miller said.

“We still have just under 200 cases where the lab report came back ‘no controlled substance’ that we need to get reversed,” Chandler said. “ We are working very closely with the public defender’s office and other appointed counsel to reach out and locate these defendants.”

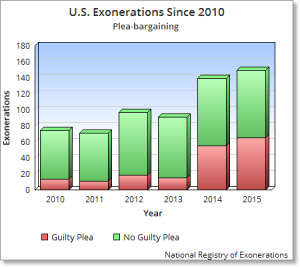

Guilty pleas were commonplace among the 2015 exonerations, accounting for 65 of the 149 total overturned convictions (44 percent), the exonerations report said.

Harris County is unique because it has scientific evidence that shows “how common it is for people to plead guilty when they are innocent — and it’s much more than you’d think,” Samuel Gross said.

But why are innocent people pleading guilty? That’s the question of the day, Chandler said.

“A large number of these defendants thought they had drugs in their possession,” she said. “They had ‘turkey dope,’ as we call it, and just didn’t know it. So when they came to court and were offered a satisfactory plea bargain, they took it.”

Many people also have bail bonds they can’t afford to pay, so they take plea bargains to stay out of jail.

“Then there is a situation where the plea bargain offered is … such a sweet deal, and it creates a cost benefit analysis of a different nature,” Chandler said. “It’s not necessarily, ‘I can’t get out so I might as well plead guilty and move on down the road.’ It’s more of a, ‘this deal is so good I don’t want to risk going to trial for fear of getting more time.’”

Some perspective: defendants who went to trial and were convicted of drug charges that carried mandatory minimum sentences received an average of 11 more years in prison than those who pleaded guilty, according to a study conducted by the Human Rights Watch in 2012.

Beyond defendants sparing themselves harsher sentences, plea bargaining is prevalent because it’s cost effective and saves courts the trouble of having to conduct trials for every person charged, according to the American Bar Association.

Still, testing evidence from cases with guilty pleas is “a good takeaway from what has happened in Harris County,” Miller said. “We know that these substances and these situations aren’t unique here, so maybe other jurisdictions need to be looking at that.”

But 62 percent of labs said law enforcement often doesn’t submit evidence for testing because of plea bargains, according to the crime lab survey.

“There’s an administrative convenience of just having it be done with, ”said Professor John Hollway, executive director of the Quattrone Center for the Fair Administration of Justice at the University of Pennsylvania Law School. “So the issue in my mind is: How do you get quicker turnaround from the lab, so that you have the information to know what you’re charging and don’t have to unwind it?”

The Harris County Conviction Review Section answered that by instituting a policy in February of 2015 that prohibits guilty pleas on drug possession cases until they receive a confirmatory lab report, Chandler said.

“We are also seeing our courts give a lot more pre-trial release bonds on low-level (drug) cases because of this project,” she said. “As we see the approach to drug cases change and evolve, we are going to see a much reduced incidence of these bad convictions.”

The drug-related cases are unique, but plea bargaining becomes a bigger problem in other misdemeanor charges where the evidence is less cut and dry, the exonerations report said.

“There are other categories of cases out there where wrongful convictions occur, and they are not always easy to identify and they are not always easy to resolve,” Chandler said. “It’s a lot more difficult to get a case overturned in Texas absent an exonerating DNA or lab report, so we are always looking for a forensic angle to push us over the edge.”

Nobody involved with the conviction process is necessarily acting in bad faith when confirmatory evidence is not tested after a defendant pleads out, but still you have someone pleading guilty to a crime he or she didn’t commit, Hollway said.

“In a system where 97 percent of all criminal cases are resolved by plea bargains, making sure we have an appropriately functioning system of plea bargaining that minimizes that risk of error in all cases is crucial,” he said.