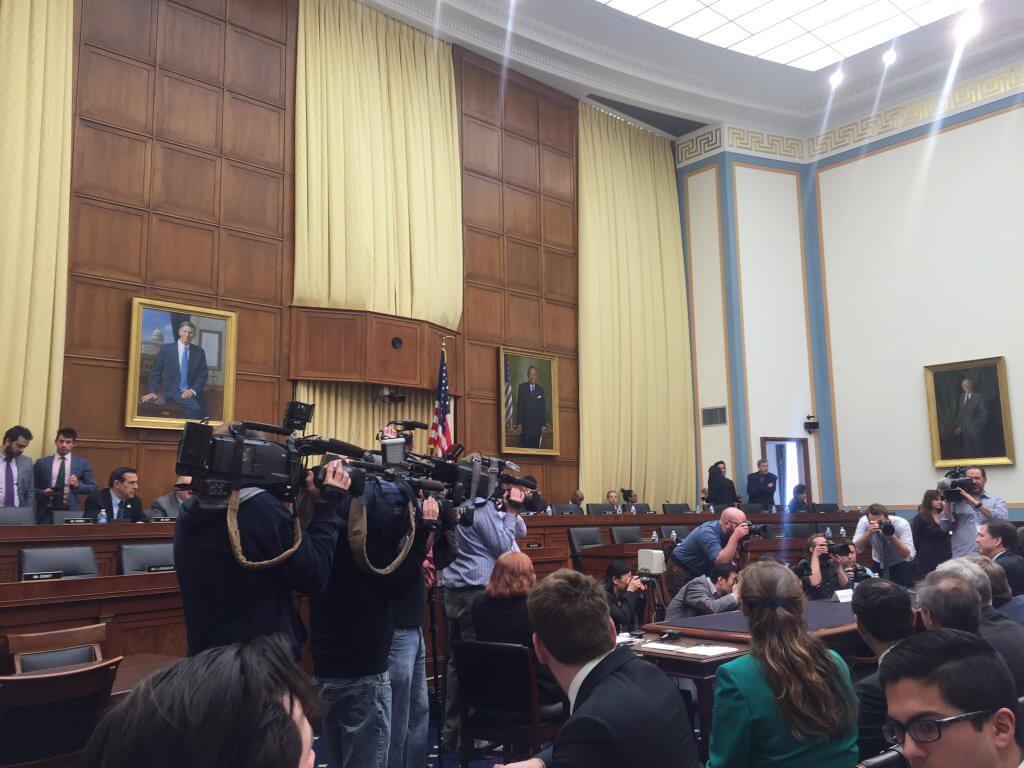

FBI Director James Comey prepares to give testimony at a House Judiciary Committee hearing on the ongoing battle over creating a so-called iPhone backdoor. (Alex Duner/Medill News Service)

WASHINGTON — The battle between Apple and the FBI over a court order to create a so-called backdoor into one of the San Bernardino shooters’ iPhones shifted from the courts to Congress on Tuesday, where House members questioned FBI Director James Comey and Apple legal counsel Bruce Sewell about balancing civil liberties with law enforcement.

Representatives were surprisingly hostile to Comey, particularly on the issue of whether the San Bernardino case would set legal precedent. The FBI had previously argued that this case is narrowly centered on the one phone, but Comey acknowledged that the court order would allow the FBI to demand that companies break on-device encryption in the future.

“Sure, potentially,” said Comey. “Any decision by a court about a matter can be useful to other courts…That’s just the way the law works.”

“We can all agree this is not about access to just one iPhone,” said Sewell.

Privacy advocates have charged that the FBI is using the emotional stakes behind last December’s attack to win a legal victory that could have broad consequences for government access to citizens’ digital information.

“Bad cases make bad law,” said Representative Zoe Lofgren, D-Ca. “This might be a prime example of that rule.”

The FBI obtained Syed Rizwan Farook’s iPhone after he and his wife killed 14 people in a terrorist attack. Authorities say that while they have access to Farook’s iCloud backups, they doesn’t contain information from the six weeks prior to the attack. The FBI wants Apple to develop a tool that will let law enforcement guess the phone’s password and open it by brute-force. Without this tool the contents on the phone will auto-erase if 10 incorrect guesses are entered.

Comey also fielded questions over how San Bernardino County reset Farook’s Apple ID password, preventing it from backing its data up to iCloud when connected to a known Wi-Fi network.

“There was a mistake made in that 24 hours after the attack, where the county, at the FBI’s request, took steps that made it impossible later to cause the phone to back up to the iCloud,” said Comey.

Comey cited the threats from ISIS and child predators, arguing that strong encryption prevents law enforcement from getting the information it needs.

“Even with a court order, what we get is unreadable,” said Comey. “It’s gobbledygook.”

“We are moving to a place where there are warrant-proof places in our lives,” added Comey. “That has profound consequences for public safety.”

House Judiciary Committee Chairman Bob Goodlatte, R-Va., said that the San Bernardino case “may not be an ideal case upon which to set precedent.”

The closely-watched hearing held by the House Judiciary Committee lasted over five hours.

Monday, a New York judge ruled in a different case that the government cannot use the All Writs Act — a 1798 statute that authorizes the courts to issue court orders for searches not covered by existing laws — to compel Apple to write code to unlock a suspect’s phone.

Comey said he has not yet read that decision.

Comey tended not to attack Apple directly, though in one heated moment, when asked to speculate on Apple’s motives in the debate he said, “They sell phones. They don’t sell civil liberties or safety.”

“This is not a marketing issue,” said Sewell. “We’re doing this because we think protecting the security and privacy of hundreds of millions of iPhone users is the right thing to do.”

The decision in the San Bernardino case will be made by a judge in California.

Comey supports the idea that the courts should resolve the San Bernardino iPhone dispute, not Congress. However, Comey also admitted that Congress has a role to play in resolving the broader “collision between public safety and privacy.”

“The administration has said they aren’t going to push Congress towards any legislation, but when you hear Comey tell them to think about this, you don’t have to be a seasoned congressional observer to understand that the Director wants them to legislate,” said Mark Jaycox, the Electronic Frontier Foundation’s civil liberties legislative lead. “It seems that the director is not in step with the broader administration policy.”

Committee members argued that Congress, not the legal system, is where the decision should occur on how to resolve the competing interests.

“What concerns me,” said Rep. John Conyers, D-Mich., “is that in the middle of an ongoing congressional debate on this subject, the FBI would ask a federal magistrate to give them the special access to secure products that this committee, this congress, and the administration have so far refused to provide.”

“These cases illustrate the competing interests at play in this dynamic policy question — a question that is too complex to be left the courts and must be answered by Congress,” said Goodlatte.

In a lighter moment, Rep. Darrell Issa, R-Ca., asked New York County District Attorney Cyrus Vance if he had “ever ordered a shredder company to put together a shredded piece of paper?”

“Of course not,” Vance replied.

Vance said that his office has over 205 iPhones with information key to criminal cases that cannot be accessed because of encryption.

Though there has been some debate over how the public feels about the issue, most of the representatives seemed to ask substantially tougher questions to Comey than they did to Sewell.

However, both Rep. Trey Gowdy, R-S.C., and Rep. Jim Sensenbrenner, R-Wisc., were upset that Apple lacked a legislative proposal to balance encryption with law enforcement.

“I don’t think you’re going to like what comes out of Congress,” Sensenbrenner told Sewell.

Sewell said Apple looks forward to being part of the legislative process.