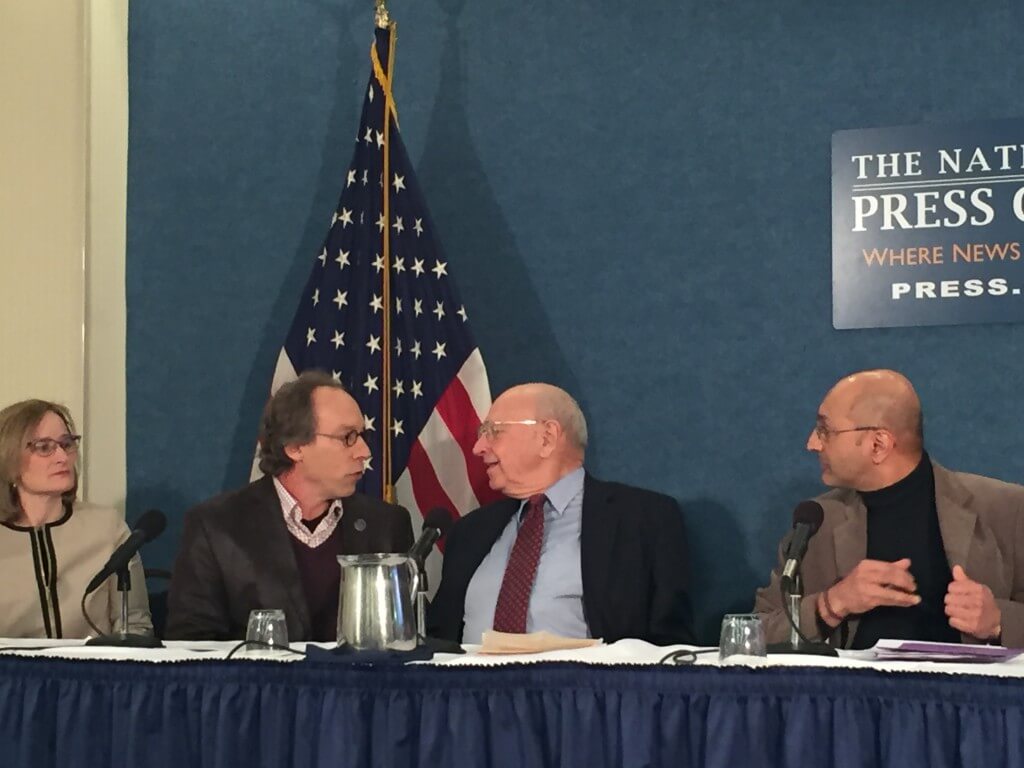

Members of the Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists discuss the Doomsday Clock and its implications on the world during an international press conference at the National Press Club on Tuesday.

WASHINGTON – In a symbolic gesture to show the world how close it is to destruction, the Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists announced Tuesday “with utter dismay” that its Doomsday Clock will remain at three minutes to midnight.

“This is a metaphor for how close we are to destroying the planet,” said Rachel Bronson, executive director and publisher of The Bulletin. “It is a summary view of leading experts deeply engaged in the existential challenges of our time.”

The clock remains the closest it has been to midnight in the last 20 years.

The Bulletin of Atomic Scientists is a journal created after World War II to warn the world of the dangers of nuclear war. In 1947, the Doomsday Clock was created with a time of seven minutes to midnight.

Each year, the Bulletin’s Science and Security board as well as its Board of Sponsors, which has 16 Nobel Laureates as members, decides where to position the minute hand. It had been at five minutes to midnight until January 2015, when it moved to three minutes to Doomsday.

Members of The Bulletin in California at Stanford University and in Washington at the National Press Club explained that nuclear proliferation and climate change were the two main reasons for not moving the clock’s hands further back from midnight.

“There is no sane use of nuclear weapons and we need to reduce our nuclear arsenal, not create a new generation of weapons,” said Lawrence Krauss, chair of the Board of Sponsors for The Bulletin. “It makes economic as well as strategic sense.”

Krauss cited growing nuclear tensions between the United States and Russia, the situation in North Korea becoming “more acute” and strains between Pakistan and India regarding nuclear armament as sources of concern.

The scientists called the Iranian nuclear deal as “a step forward, a relatively bright spot in a difficult horizon.” Yet, despite positive rhetoric, Thomas Pickering, a former U.S. Ambassador to the United Nations, admitted the deal is “not yet a kind of perfect, absolute certain step ahead.”

The recent Paris agreement on climate change also was noted as a positive move.

Sivan Kartha, a senior scientist and climate change expert at the Stockholm Environment Institute, criticized “an inadequacy of efforts” by governments to combat climate change, but highlighted the Paris agreement as a “tentative success.”

The nations involved in the December agreement adopted a joint goal of keeping the earth from warming more than two degrees centigrade above its pre-industrial average temperature.

“Sooner rather than later the strong aspirational goals of the Paris agreement will need to be matched with actions that are equally strong,” said Kartha.

The scientists said people should demand stronger laws and international agreements to reduce both climate change and nuclear proliferation.

“Citizens have a vested stake in the outcomes of climate change and nuclear security,” said Bronson. “Individuals need to care because they can actually make a difference in a safer planet.”