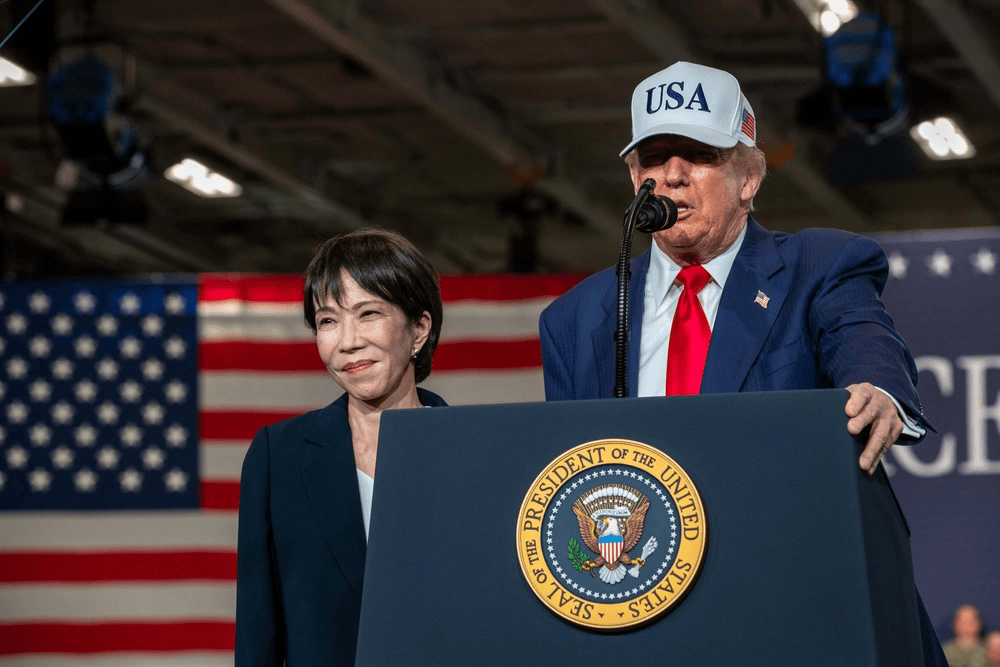

After what many called a successful meeting with President Donald Trump, Japan’s new prime minister Sanae Takaichi is leading a major change to Japan’s decades of pacifism: an increase in the defense budget.

Takaichi announced during her first parliamentary address as prime minister that Japan would increase its defense spending to 2% of the nation’s gross domestic product (GDP) by March 2026, nearly a year earlier than the proposed timeline announced in 2022 by former Japanese Prime Minister Fumio Kishida.

This change in the defense budget timeline highlights the evolution of the United States-Japan relationship as the U.S. is beginning to encourage its allies to arm themselves and build a stronger defense.

Trump released the official United States National Security Strategy last week, which sets up the president’s defense goals and budget for his term. Among the major points were continued pressure on American allies, including Japan, to increase defense spending in support of American efforts to “harden and strengthen our military presence in the Western Pacific.”

“The Japanese, particularly the nationalists, have wanted…to spend more, and now the Americans, instead of telling them ‘no, don’t’, are now in a position where we’re encouraging them to do so,” said Brad Glosserman, senior advisor and Japan expert at the Pacific Forum. “The confluence of American calls for greater Japanese participation and contribution—with the conservative desire to do more— has aligned well.”

In the past, Japan held itself to a defense budget that is 1% of its GDP by keeping certain programs out of the category of defense spending. Glosserman said that the new increase in defense budget is not necessarily more money but a recharacterization of some current programs as defense spending that they once excluded.

“The Japanese managed to take out… things that most NATO [North Atlantic Treaty Organization] countries would include, such as the Coast Guard and pensions for their military officers,” Glosserman said. “Now, what they’ve done is turn that stuff back in, and my understanding, this is a crude estimate that the call to double defense spending of 2% of GDP… at least half of that increase is nothing more than putting back in the accounts things that were taken out.”

This restructuring of the defense budget comes amid escalating tensions in the Pacific region. Takaichi has found herself in hot water with China less than two months into taking office. In November, during a speech to the Japanese parliament, Takaichi said that a Chinese attack on Taiwan would be “a situation threatening Japan’s survival” and could prompt deployment of the Japan Self-Defense Forces. Chinese officials viewed that as an attack on their so-called claim of Taiwan as a Chinese territory, making charged statements online that appeared to many in the region as threatening.

As tensions continue to rise with countries like China, Japan is internally grappling with its own rules about war. Article 9 of its constitution states Japan will “renounce war as a sovereign right of the nation” and was written after World War II ended. However, Japan established its self-defense forces in 1954 to prepare for possible attacks from foreign powers.

Former Japanese Prime Minister Shinzo Abe called for amending Article 9 to expand the powers of the self-defense forces. While there have been no formal amendments, Abe expanded the Japan Self-Defense Forces in 2015 to allow collective defense to assist Japanese allies, including the United States, if they are attacked. Retired U.S. Army Col. John Hansen, who is an adjunct professor of political science at Hawaii Pacific University, said that despite these growing regional tensions, Japan is unlikely to formally amend the constitution.

“Article 9 is essential. To even hint at aggression or offensive acts, the Japanese people will not abide in that. I think they can ramp up their defense, and there’s a deterrent effect with having credible, overwhelming capability to strike back, but not to use it in an offensive way,” Hansen said.

However, the United States has recently become more involved in other regions of the globe, with some conservative party members in the Japanese parliament worrying that the United States is pushing Japan to the side. Glosserman said that Japan has always had concerns that the United States could abandon the relationship forged through decades of diplomacy.

“Historically, relationships in Asia have been fundamentally different from alliances in Europe precisely because you don’t have a multilateral security architecture like NATO,” Glosserman said. “The Japanese have always worried about whether the United States was going to give them the attention they deserved and…whether the U.S. would honor those obligations in the way that the Japanese consider them.”

Karen Knudsen, chair of the board of directors of Japan-America Society of Hawaii (JASH), said the close relationship between the United States and Japan is a result of how the United States handled Japan after World War II.

“We could have tried [the Japanese emperor] for war crimes, we could have hanged him, and we didn’t,” Knudsen said. “We preserved him, although we moved the powers, but we were able to work with the people of Japan and build a strong alliance.”

Last August marked 80 years since the United States dropped the atomic bomb on the Japanese cities Hiroshima and Nagasaki, leading Japan to surrender and ultimately ending World War II. Since then, a nuclear bomb has not been used in war, but many countries in the Pacific region have proliferated nuclear weapons.

Trump declared on Truth Social in late October that he was instructing the Pentagon to begin nuclear testing again. This comes decades after a Congressional-led voluntary moratorium from 1992 and the United States’ signing of the Comprehensive Test Ban Treaty in 1996, both barring nuclear testing. Trump’s argument is that other countries are also testing nuclear weapons and that the United States should be testing “on an equal basis.”

“Everybody’s always responding to everyone else, but they’re also responding to the belief that broadly speaking, nuclear weapons are key to national security, are an indicator of national status and prestige,” Glosserman said. “The biggest issue we need to be worried about in the region is the degree to which the Americans are turning a blind eye or actively encouraging our friends and allies to consider proliferating nuclear capabilities.”

Hansen echoed the idea that nuclear weapons are seen today as a status symbol. He said there is “a security dilemma” going on that is pushing countries in the region to proliferate nuclear weapons, with China, Russia and North Korea each possessing a nuclear arsenal. South Korea has been debating starting a nuclear program as well. That leaves Japan, which is wary of nuclear weapons because of its past.

“If you have a neighbor or a would-be aggressive neighbor that’s arming themselves with tremendous capability, then that impels you to do likewise. The dilemma is that the one that’s arming themselves sees a gap that they’re trying to fill, to bring parity… so you get this arms race,” Hansen said. “If you want to be heard in the international discourse, you arm yourself with nuclear weapons, and then people will pay attention. That’s kind of the bizarre rationale.”

“It’s so important to de-escalate. We’ve got to do that. I’m a soft diplomacy type of person,” Knudsen said. “Governments do weird things but you’ve got to maintain the people contact, so when things get back to normal, hopefully, you can rebuild that relationship.”