WASHINGTON – Officials at three federal agencies responsible for preserving records and history said Wednesday that artificial intelligence has the ability to improve their jobs, but several lawmakers on the Senate Rules and Administration Committee urged caution in using the technology.

“There is no question that AI is informative, and it is poised to evolve rapidly,” ranking member Deb Fischer (R-Neb.) said in her opening statement. “While AI raises the possibility of creating efficiencies and competitive advantages across [the] government, it also creates risk.”

Carla Hayden, who leads the Library of Congress, testified that AI allows for collaboration across workplaces in both the private sector and government and that making the agency more digitally oriented has been a “key focus” of hers since she became the librarian of Congress in 2016. The Library of Congress’ current strategic plan embraces the central idea that technology must be “baked into all that we do,” she said.

But several committee members noted that high-profile cases of false images and videos have led them to be skeptical. For instance, Sen. Bill Hagerty (R-Tenn.) cited worries over the digital manipulation of voice recordings, a term known as “deepfaking,” in the music industry.

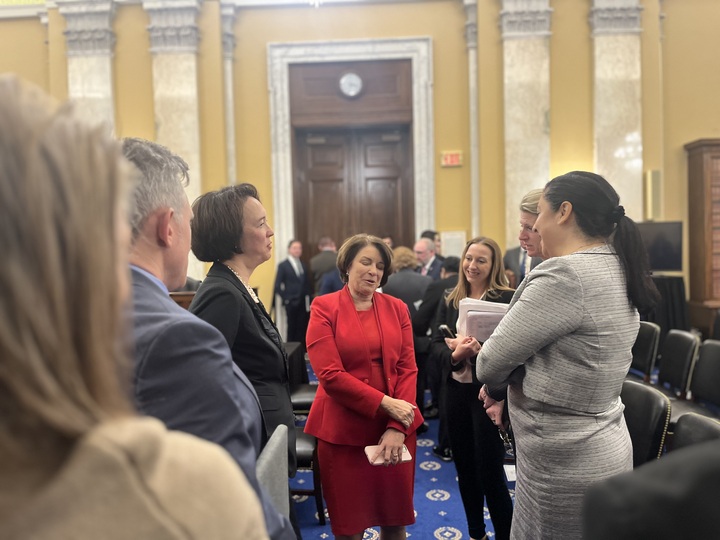

Chair Amy Klobuchar (D-Minn.) also emphasized the threat deepfaking poses to fomenting misinformation about candidates and polling results during the 2024 election cycle. She referenced bipartisan legislation introduced in September 2023 sponsored by Sens. Josh Hawley (R-Mo.), Chris Coons, (D-Del.), and Susan Collins, (R-Maine), to prohibit fraudulent AI-generated content in elections.

“There’s some very interesting cross-party support in making sure that our democracy is safe from deep fakes,” Klobuchar said in an interview with the Medill News Service. “I don’t care if you’re a Democrat or Republican – your image and your voice can be used in fake ways.”

While acknowledging the risks associated with breaches to cybersecurity both at the individual and federal levels, Smithsonian Deputy Secretary Meroë Parks praised the ability of AI and other technologies to enable newfound understandings of cultural history.

One positive example of technology she cited was the Freedmen’s Bureau’s transcription project, which is the Smithsonian’s largest crowdsourcing initiative and transcribes genealogical records of the formerly enslaved. Other data science labs aim to discover historical contributions by women mistakenly attributed to men.

“We and other cultural institutions can collaborate with technology leaders to help improve AI tools, not only for our own use, but for everyone’s,” Parks told lawmakers. Like Hayden, Parks noted the opportunity AI presents for collaboration, especially in higher education.

Hugh Nathanial Hawthorne, director of the Government Publishing Office (GPO), was more cautious, noting that his agency differs from the Library and Smithsonian by producing information on behalf of all three branches of government.

“GPO’s current processes are just as susceptible to disruption from AI as those in any other billion-dollar enterprise,” said Hawthorne.

As companies debate the use of AI in private enterprise, Klobuchar and committee members are continuing to examine its impacts on government agencies.

“[AI] is something that we, in Congress, have to deal with using guardrails,” said Klobuchar. “We must continue working to stay ahead of the curve.”