When Democratic representative-elect Cleo Fields went to the Cannon House Office Building on Capitol Hill during new member orientation in November, it was like stepping into the past. The Louisiana politician was back where it all began for him in 1993, when he served two terms as a representative of the Bayou state’s Fourth District.

“32 years ago, I started walking these halls,” Fields said. “To have never had a dream of actually coming back and walking the same halls, it was just a little surreal.”

He’ll represent Louisiana’s Sixth District starting in January, succeeding Republican Rep. Garret Graves. Almost 400 miles away in Mobile, Alabama, 39-year-old Shomari Figures is also getting ready to serve in Congress for Alabama’s second Congressional District, beating the Republican candidate and flipping the seat.

The incoming freshmen share more in common than party affiliation; after legal victories forced redistricting in both states, the states drew new maps, and created an extra majority-black district in each state, advancing equal representation in Congress. Fields and Figures intend to represent the needs of all their constituents and serve their interests in the House of Representatives.

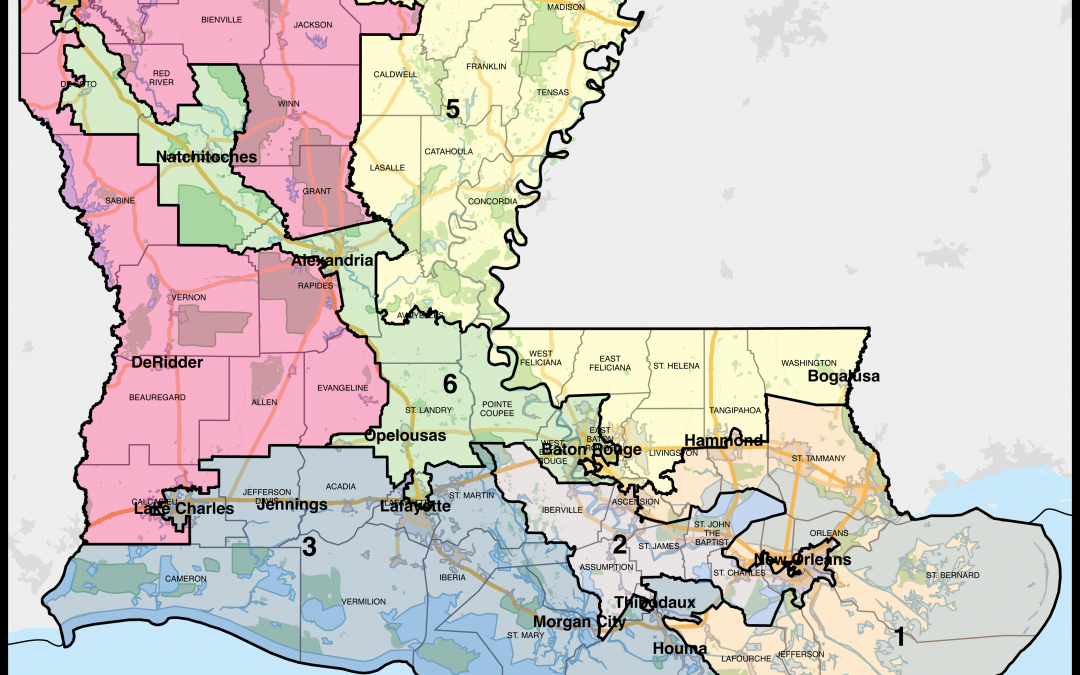

Louisiana’s new map was created in January 2024 after legal battles led the state legislature to submit a new electoral map with two majority-black districts. The process began when multiple individual plaintiffs and civil rights organizations filed a lawsuit in federal district court in March 2022 against then-Louisiana Secretary of State Kyle Ardoin. They successfully argued the previous electoral map violated the 1965 Voting Rights Act (VRA) because it gave Black Louisianians, a group almost one-third of the state’s population, just a single majority-black congressional district out of the state’s six districts.

Figures’ district in Alabama was created through similar means.

The Supreme Court’s 2023 decision in Allen v. Milligan said the Alabama electoral maps likely violated the VRA too, and required the creation of a second majority-minority district. However, after negotiations on new maps, the new second district ended up being an almost-majority district.

Figures’ election victory set him on a path following in the footsteps of his family– a group of dedicated public servants in Alabama. His late father Michael Figures and uncle Thomas Figures prosecuted the Ku Klux Klan after the 1981 lynching of 19-year-old Michael Donald, bankrupting the United Klans of America. His father later served as president pro tempore of the Alabama Senate. His mother, Vivian Figures, took over her husband’s state senate seat after he died, and continues to serve there now.

After winning, Figures said he felt a strong sense of gratitude towards “the plaintiffs in the [Milligan] lawsuit and the people who fought and sacrificed so much decades ago to have a Civil Rights Act and a Voting Rights Act to get us in the position where we even had this opportunity in the first place.”

He said it’s “a very humbling feeling and an honor” to represent people in his hometown of Mobile.

Fields and Figures agree justice prevailed in the rulings, however, for the 62-year-old Fields, these victories are long overdue. He said it was frustrating during his time as a state legislator to see fair representation remain unmet.

It was also a problem he dealt with during his first stint in Congress. In his four years serving in the House, he represented what was the state’s second majority-minority district in a seat, he said, was constantly under attack. It was eventually dissolved after a 1997 Supreme Court decision deemed Louisiana’s map unconstitutional because of racial gerrymandering.

“I don’t understand why there are some people who just don’t feel that diversity and inclusion is important,” Fields said. “I mean, all of the people should enjoy the opportunity to participate in its government.”

On Capitol Hill, several Black members of Congress felt justice had been achieved thanks to the shifts in state maps and the resulting election victories. Even so, frustration remains.

Yvette Clarke (D-N.Y.), who was recently selected to serve as the next chair of the Congressional Black Caucus (CBC), called the previous maps “deliberate discrimination.”

“You would think in the 21st century, we wouldn’t be revisiting these old racially divisive issues,” said Clarke. “We still have to continue to fight and be vigilant around voting rights in America.”

According to Clarke, Fields and Figures will not only represent their districts but also advance the long-term push for building the coalition among black leaders on Capitol Hill. The CBC in the new Congress will be the largest yet with 62 members.

Some current members recall when the CBC was considerably smaller, like Rep. Sanford Bishop (D-Ga.). He was first elected to Congress the same year as Fields in 1992.

When Bishop first stepped foot inside the Capitol Building, the caucus had just 40 members. He said the steady increase has “strengthened the legislative muscle of minorities.”

At the same time, there are also worries that progress will be reversed, particularly in 2030, when state electoral maps will be redrawn after the decennial census. Rep. Kweisi Mfume (D-Md.), who chaired the CBC from 1993 to 1995, said the outcome of the population count could put Black voters in the same position. He said state electorates may use the 2030 numbers to redraw the districts again and remove the second majority-minority districts in Louisiana and Alabama.

And that’s not the only factor potentially shifting the new Louisiana and Alabama maps back either.

Earlier this year, a group of 12 white Louisiana voters filed a lawsuit in a different federal court, alleging the new map unconstitutionally conducted racial gerrymandering in its own right. The federal court ruled to stop the new map from passing, but the Supreme Court argued it was too close to the election to issue a ruling, putting an emergency stay on the case and allowing S.B 8 to stand. The Supreme Court is scheduled to hear the lower-court case next year.

In Alabama, Secretary of State Wes Allen, the defendant in Allen v. Milligan, said in a statement that legal actions are not over and expressed hope for a full hearing in the future.

Nonetheless, CBC members, old and new, said the victory is a critical win in a constant battle for justice, one they say they’re willing to continue to wage.

“Opportunities have always come with scars and struggles,” Fields said. “It just proves that you gotta fight for every inch.”