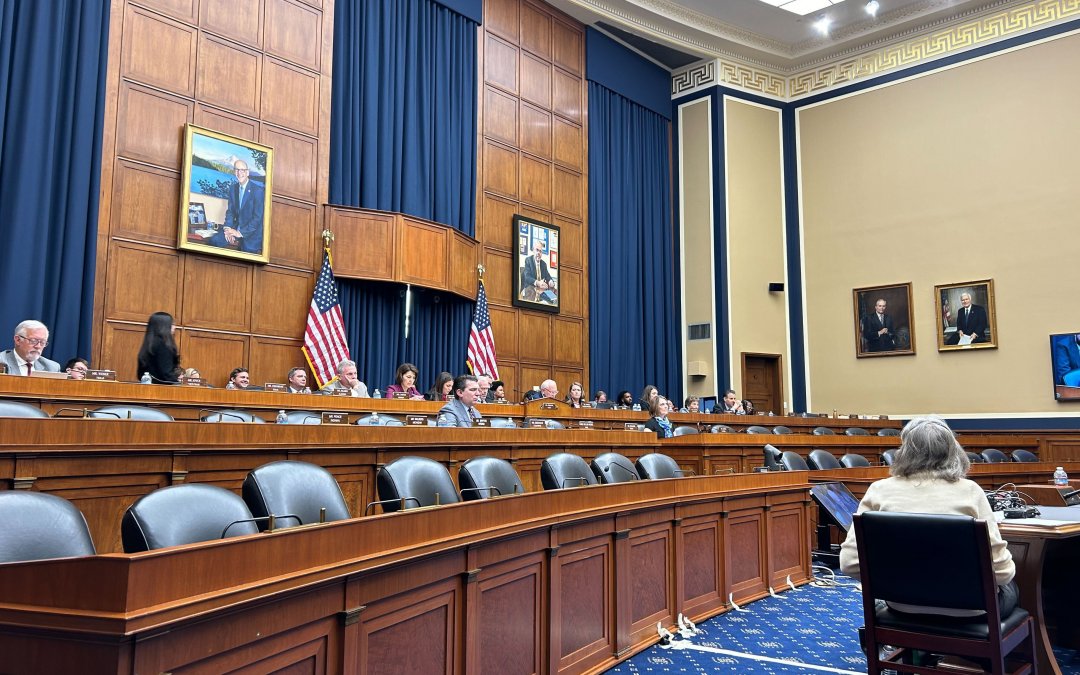

WASHINGTON – The Environmental Protection Agency’s new methane emission regulations drew rebuke from House Republicans on Wednesday when they said small and midsize oil and gas companies would struggle to survive, while Democrats and environmental advocates called to further tighten the regulations to limit pollutants and protect human health.

In August, the EPA expanded the Clean Air Act’s emission regulations of greenhouse gases for the oil and gas industries, including adding a methane emission reporting program. The rule was created in response to the 2022 Inflation Reduction Act and President Joe Biden’s executive order on the first day in office in 2021 calling for federal agencies to take necessary actions to “immediately commence work to confront the climate crisis.”

The regulations require companies to report their emissions and includes provisions that facilities releasing above a certain amount of methane must pay for each metric ton above this level. Methane is a potent greenhouse gas responsible for one-third of global warming that poses severe public health risks.

House Republicans labeled the fee a “methane tax” and brought in several small oil and natural gas producers who testified that they cannot afford to stay in business if the fees are enacted. GOP members emphasized that the U.S. is an energy production leader, advocating for a reduction in regulation.

“We have achieved this while also reducing emissions more than any other nation,” House Energy and Commerce Committee Chair Cathy McMorris Rodgers (R-Wash.) said at the hearing. “We should be celebrating this legacy and building on our achievements.”

Drew Martin, a cofounder of Miller Energy Company, a small Michigan company with 56 employees, said in prepared testimony that if the EPA regulations “are implemented as written, my business and the business of many of my peers in Michigan will end abruptly.” He explained that mature oil wells like the ones his company operates “simply don’t have the volume, pressure, and associated emissions to be burdened with the energy, effort, and cost associated with complying with these regulations as written.”

McMorris Rodgers told the Medill News Service her greatest concern with the regulations is their impact on small and midsize businesses, like Martin’s. She referenced the statistic that 300,000 of 750,000 small oil and gas businesses could be put out of work as a result of the regulations.

Other Republicans added that the challenge of interpreting and implementing the regulation will burden companies and consumers alike.

Earthworks Policy Director Lauren Pagel pushed back on such criticism. “Today’s hearing was an attempt by industry cheerleaders to prioritize profits over people,” Pagel said in a statement to Medill News Service.

But Joseph Goffman, principal deputy assistant administrator for the Office of Air and Radiation at the EPA, said in his written testimony that the new rule will yield the equivalent of “$7.3 to $7.6 billion a year from 2024 to 2038, after accounting for the costs of compliance and savings from recovered natural gas.”

“Any increases in the sales price for crude oil and natural gas are expected to be small,” he said.

Democrats argued that firmer regulations are necessary to combat the current climate emergency and invest in the planet’s future. Rep. Diana DeGette (D-Colo.) said protecting the environment and preserving industry is “not a zero sum game.”

Democrats for their part pointed to the benefits that controlling pollutants would have on Americans’ health. Many of Rep. Nanette Barragán’s (D-Calif.) constituents have asthma, which is associated with living near oil and gas production facilities, she said. According to Goffman, the methane controls the EPA is setting are projected to prevent up to 97,000 cases of asthma symptoms.

Similarly, Rep. Scott Peters (D-Calif.) said he was disappointed with Republicans opposing all regulation and said collaboration could make it possible to come up with a mutually beneficial solution.

“I really want to work on this in a bipartisan way, and this is what I get: not a discussion of how to get better regulations,” Peters said. “But an idea that we should just get rid of all the regulations entirely, and I am really frustrated by this.”