WASHINGTON — Tribal leaders on Wednesday urged the federal government for more money and law enforcement support to help them tackle the spread of fentanyl – a synthetic opioid that is up to 100 times as potent as morphine – in Native communities.

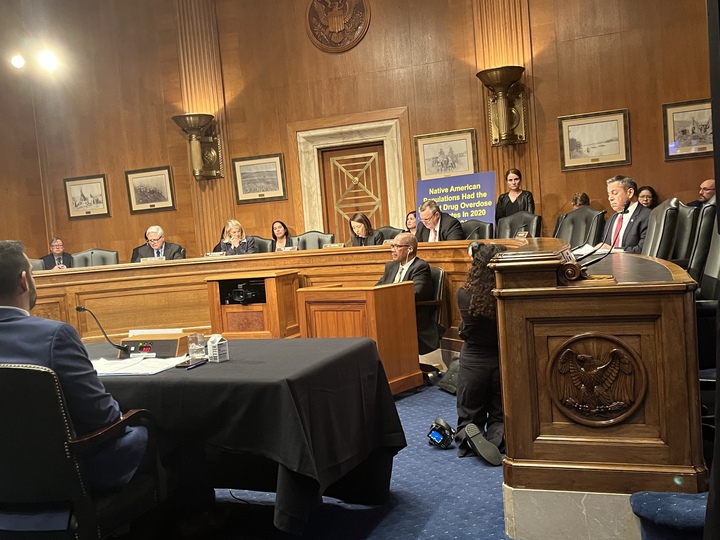

At a Senate Indian Affairs Committee hearing, Native leaders said attacking the fentanyl crisis requires an increase in law enforcement, more funding to prevention and rehabilitation centers, and more authority for the tribal justice system.

There has been a stark rise in fentanyl-related deaths over the five years since the Senate Indian Affairs Committee addressed drug addiction. From 2020 to 2021 alone, American Indian and Alaskan Natives had a 33% rise in drug overdose deaths, and Native Hawaiians and Pacific Islanders saw a 47% jump, according to data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

“These fentanyl-related deaths have impacted every area of our lives, as our community is left in constant grief and sorrow as we are barely able to lay our loved one to rest before we get word of the next,” Tony Hillaire, chairman of the Lummi Indian Business Council in Washington state, said in his written testimony.

Tribal governments do not have the power to hold non-Indian drug dealers accountable in their justice system, making prosecutions out of their hands.

Under the current system, tribes must see if their counties have enough space for non-tribal members they arrest, said Bryce Kirk, councilman of the Assiniboine and Sioux Tribes of the Fort Peck Reservation in Montana.

“I almost feel like Indian country is being targeted, that people know that you don’t have the law enforcement, that you don’t have the capabilities and that’s where people are setting up shop,” said Sen. Lisa Murkowski (R-Alaska).

Hillaire urged the federal government to declare a national emergency to fentanyl and send more resources to the Bureau of Indian Affairs, the FBI and other government agencies.

After four overdoses occurred within four days in September, the Lummi Nation declared a state of emergency, which allowed for leaders to take more aggressive steps toward targeting the distribution of fentanyl, he said. After a partnership with the FBI to implement checkpoints and establish K-9 units, Hillaire said authorities confiscated 4,500 pills on the reservation within a few days.

Jamie Azure, chairman of the Turtle Mountain Band of Chippewa Indians of North Dakota, said his tribe established its own tribal Division of Drug Enforcement, which currently has four staff members. Previously, the tribe had only one agent from the Bureau of Indian Affairs Office of Justice Service who had to cover five reservations in North Dakota.

Witnesses at the hearing agreed an increase in law enforcement alone will not solve the crisis, and that treatment and rehabilitation, often scarce, should be a priority.

Dr. Claradina Soto, a public health professor at the University of Southern California, said providing appropriate housing, such as offering culturally centered sober living facilities services, is a critical part of recovery.

Many Native Hawaiian members in her community prefer traditional healing practices, said Dr. Aukahi Austin Seabury, executive director of I Ola Lāhui, a nonprofit organization that provides behavioral health care to predominantly Native Hawaiian communities. She said the health system needs funding to support behavioral health and medicine that incorporate cultural practices.

Kirk, who lost two people he considered his “brothers” to fentanyl this year, said the fentanyl crisis’s reach has spread to all ages.

“We are very close and losing the generation to an opioid, to synthetic drugs.” Kirk said. “We need to figure out a way that we can work together to address a lot of these issues.”