WASHINGTON — President Joe Biden has long been vocal about lowering drug prices nationwide, but his plan has avoided a part of the problem.

Pharmacy Benefit Managers, or PBMs, comprise a $450 billion industry and are crucial in determining the costs consumers pay at the drugstore. These little-known middlemen negotiate prices between health insurers and drug manufacturers, though not much is exactly known about their actions.

Questions on PBM practices mainly focus on rebates, a discount given by the drug manufacturer to these middlemen. PBMs place the best-discounted drugs higher on their distribution lists, known as formularies, to the pharmacies they work with.

There’s been little to no government oversight of their practices ever since the sector gained a foothold in the 1970s. After years of activism by patient advocacy groups, Congress is finally looking at regulating these mysterious middlemen, but the Biden administration continues to focus solely on manufacturers.

Anne Cassity, senior vice president of government affairs at the National Community Pharmacy Association, which represents independent pharmacies across the nation, said activists have been integral in bringing the role PBMs play to Congress’ attention.

“I’m going to give community pharmacy much of the credit because they have been carrying this and screaming from the rooftops for the last 18 years,” she said.

But she said there’s been a significant increase in involvement over the past few years; patient groups, physicians and state Medicaid agencies are now all calling for action.

PBMs market themselves as expert negotiators who secure lower drug prices, but slowly there’s been more and more questions about if those benefits are actually trickling down to the consumer, according to a representative from the National Association of Insurance Commissioners.

A 2021 study found that drug rebates are increasing costs for all consumers –– medications go up an average of $6 for those with private insurance, $13 for people on Medicare and $39 for people without insurance.

Grassroots groups like Patients for Affordable Drugs Now have pushed for transparency in PBM practices.

“We have called on Congress or the Federal Trade Commission to investigate PBMs, and basically just lay it all out,” Sarah Kaminer Bourland, the organization’s legislative director, said. “Are they doing right by patients? Or are they lining the pockets of their shareholders?”

Advocates for changes in the industry speculate that in exchange for better placement on PBM formulary lists, manufacturers have been raising their prices to have more attractive rebates and secure better placement on formularies. But, little to nothing is known about what happens behind closed doors between PBMs and drug manufacturers.

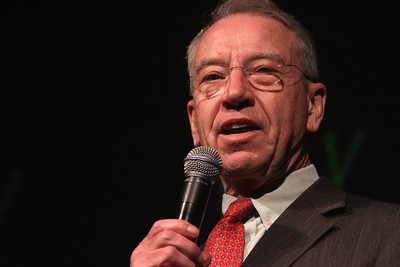

Congress is starting to try to increase transparency through legislation. The Pharmacy Benefit Manager Transparency Act of 2023, a bipartisan bill introduced by Sen. Maria Cantwell (D-Wash.) and Sen. Chuck Grassley (R-Iowa), aims to discover what PBM’s practices actually are.

“We’re trying to bring daylight into that very dark corner,” said a staff member for the Senate Commerce Committee, which Cantwell chairs. “How does all this work when you have a particular entity that has all of the information about pricing in the market, and it’s the only entity that has all that information? There are all the opportunities for mischief and arbitrage.”

The bill seeks to require that PBMs publicize their negotiations and make sure drug companies aren’t inflating prices. PBMs would have to file annual reports with the Federal Trade Commission under the bill. It also says PBMs are required to pass along 100% of their rebates to health plans or payers so they can’t pocket a portion of the discounts.

Representatives for both Grassley and Cantwell said they are hopeful about the bill’s opportunity to advance, thanks to its bipartisan nature. A hearing about the bill was held last month in the Commerce Committee, but it has yet to receive a vote.

The bill’s limited provisions mean it’s only a first step at solving this problem, according to Cassity. “I don’t think there’s one golden bullet to sort of stop all these practices,” she said. “I think this is a really good step, but there’s going to be multiple steps.”

Still, Cassity said, the bill allows the FTC to go after PBMs engaging in bad practices. She said that’s a 180 from how the FTC has viewed consolidation and its impact on consumers in the past.

Only three PBMs control more than 80% of the market –– making them incredibly powerful. CVS Caremark, Express Scripts and United Health’s Optum Rx have slowly become large conglomerates through mergers over the last two decades.

The Pharmaceutical Care Management Association, which represents the major PBMs, wholly opposes legislative intervention on their practices, saying PBMs have a proven track record of securing savings for consumers.

“Any assertion that pharmacy benefit companies increase drug costs is false. The fact is PBMs are the only member in the prescription drug supply chain that are negotiating to lower costs,” the association said in a statement to the Medill News Service. PCMA contends drug companies set and raise prescription drug prices, independent of their relationship with PBMs.

The association has also said bills like Grassley and Cantwell’s risk increasing costs for patients rather than lowering them.

Groups seeking to change the practices say PBM’s lobbying influence over lawmakers poses an obstacle.

“Both pharmacy benefit managers and drug manufacturers are highly profitable industries, which makes them very powerful forces on Capitol Hill,” Kaminer Bourland said. “When they try to dissuade Congress from doing something to investigate or reforms or industry, I do think in many ways, they are making threats.” But even with their lobbying power, members across the aisle are taking a second look.

Earlier this month, the Republican-controlled House Oversight committee called on the three large companies in the industry to turn over any documents, communications, and any information related to their behaviors.

Despite significant bicameral congressional action, the White House has yet to highlight the problem. In Biden’s State of the Union Address last month, he targeted only manufacturers in his remarks about drug pricing.

Cassity said she is hoping the administration will start to focus on the issue. “We would like the White House to engage more,” she said. “Unfortunately, they really have been silent on the PBM issue. Hopefully that might change with all the noise we’re seeing come out of Congress already.”

The White House directly declined to comment, referring questions to the Center for Medicare and Medicaid Services. The Center said it is committed to working with President Biden and other actors to help Americans access affordable prescription drugs.

But a spokesperson for Grassley said PBMs must be a target of the administration to accomplish that goal.

“If President Biden is serious about lowering the cost of prescription drugs,” the spokesperson said, “we must look at all aspects of the prescription drug industry.”