WASHINGTON – For Senate Special Committee on Aging Chairman Bob Casey (D-Pa.) and ranking member Tim Scott (R-S.C.), Thursday’s hearing on dual-enrollment in Medicare and Medicaid was an opportunity to tout an accomplishment all too rare in today’s political climate: a true bipartisan legislative collaboration.

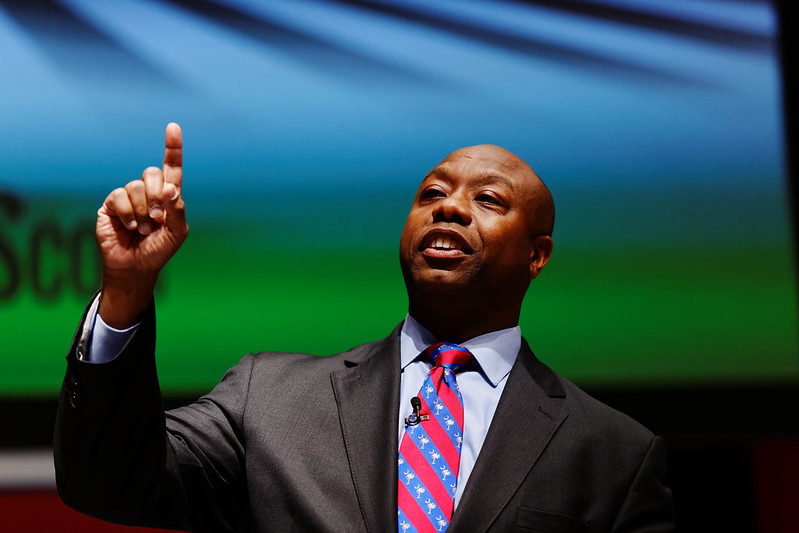

“One of the things I enjoy and appreciate about this committee,” Scott said, “is that we put seniors first, and not red ones or blue ones, Black ones or white ones, just seniors.”

To put seniors first, in Scott’s parlance, Casey announced the introduction of the Program of All-Inclusive Care for the Elderly (PACE) Expanded Act.

The bill, Casey said, “would reduce administrative barriers that prevent the development and expansion of PACE programs” that “enable people with Medicare and Medicaid to receive all their benefits through a single organization, providing primary care, long-term care and more in one place.”

For many elderly Americans, this legislation comes not a moment too soon.

Jane Doyle, a resident of Bartonsville, Pennsylvania, and grandmother of three, was diagnosed with multiple sclerosis over 20 years ago. Because of further medical complications, she has been unable to work since 2017. In Pennsylvania, Doyle said, Medicaid offers a waiver for home care expenses.

“Our family viewed this as a great alternative to a nursing home,” said Doyle, “but to qualify, someone must first apply for Medicaid and then apply for the waiver. This process was long and difficult.”

Harvard University associate professor and physician at Boston’s Brigham and Women’s Hospital Dr. Jose Figueroa said that — though the American health care system is difficult for anyone to fully comprehend, regardless of status — the process is “far more difficult for the 12.3 million dual-eligible patients living with disability, serious mental illness, frailty, multiple chronic conditions, and importantly, living in poverty.”

“One of the greatest failures of our health care system,” said Figueroa, “is that so much of dual-eligible patients’ time is lost navigating the complex and confusing rules and regulations of the two programs, which they must do to ensure they get the care and services they need.”

Eunice Medina, chief of staff of South Carolina’s Department of Health and Human Services, also stressed the importance of making the dual-enrollment program easier to understand.

“Streamlining programs and focusing efforts and funding on an integrated program,” Medina said, “can help avoid confusion and administrative burden among dual beneficiaries and providers.”

“When states are looking to integrate care,” Medina noted, “they may also need to consider the capacity of their Medicaid agency to manage the programs they have already committed to … resources that would allow states to strengthen their agency to support these massive internal and external changes would be most welcome.”

Scott surely embraced Medina’s analysis with open arms.

“To help states further improve coverage,” Scott said, “I have introduced legislation to provide further assistance to state Medicaid agencies to help integrate coverage. It creates a $100 million grant for states to improve care coordination for their dually-eligible population.”

“You have so many layers of complexity in your life as you age,” he said. “If we can eliminate any of it, it helps all of it.”