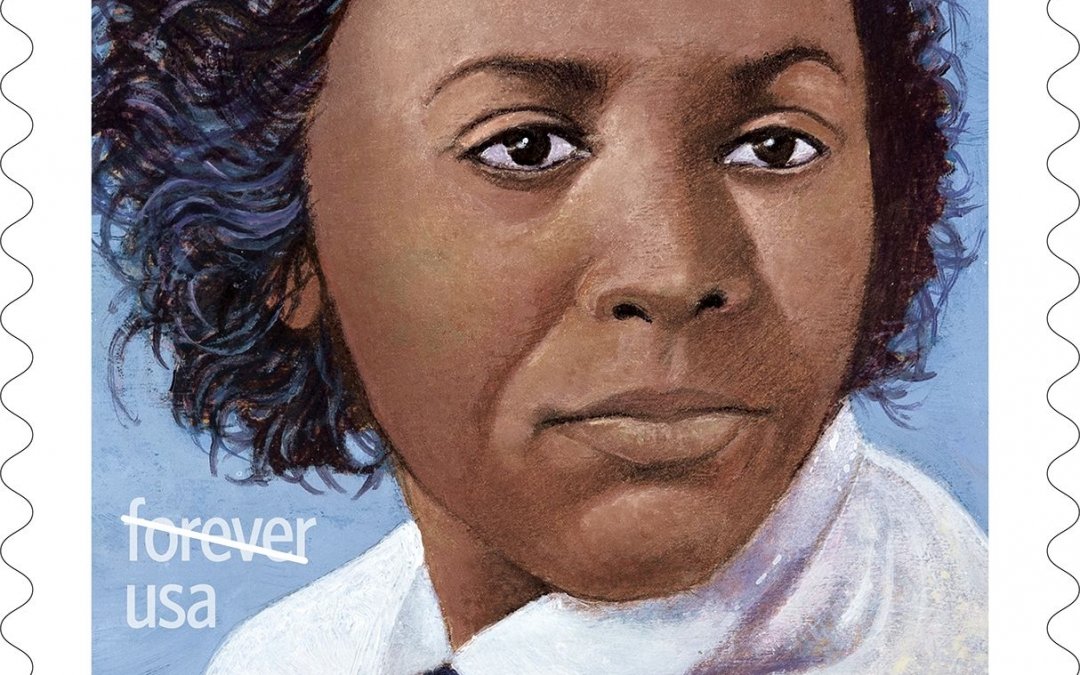

WASHINGTON – Rensselaer County native Edmonia Lewis, the first Black and Native American sculptor to earn international recognition, became the newest face of a U.S. Postal Service’s stamp at a ceremony in the Smithsonian American Art Museum on Wednesday.

“Lewis’s achievements cannot possibly fit on a postage stamp, but I think it’s so fitting to honor her legacy in this way,” said Karen Lemmey, the Lucy S. Rhame curator of sculpture at the museum.

“It is collectible and some may wish to collect and preserve it just as we do our sculptures here, but I think Lewis would be equally pleased to know these stamps will be zipping around the country just as she did,” Lemmey added.

Lewis, like many other sculptors during the 19th century, traveled to Rome to study and work as a sculptor. However, unlike her peers who could rely on their professional carvers, for economic reasons and to preserve her reputation, Lewis did some of this carving herself, according to Lemmey.

“Everything she’s done, it’s a true testament to her courage,” said dedicating official Joshua Colin, the Postal Service’s chief retail and delivery officer. “You don’t have a lot of Black sculptors, that goes for female or male, so she’s a trailblazer.”

Throughout the event, speakers, including Alex Bostic, the stamp’s artist, and Howard University’s Gallery of Art Director Lisa Farrington, reiterated their hope that the stamp would help more people learn about Lewis and detailed what set Lewis apart from her peers.

Lewis’ work has “qualities that one would only see from a woman sculptor,” Farrington said. “[She] was upset periodically because people said, ‘well, she’s only popular because she’s exotic and different,’ and she knew better. As you can see from her sculptures, they measure up to any by her white male peers of the time.”

During Wednesday’s unveiling, the museum displayed, “The Death of Cleopatra,” one of Lewis’ most well-known works, which many assumed had been lost until the 1980s.

“It was so thoroughly lost that I, along with most people who were at all interested in finding out about it, feared, for good reason, that it had been destroyed,” said Marilyn Richardson, an art consultant and the person who found the work in an abandoned storeroom at a suburban Chicago shopping mall roughly three decades ago.

“It was just an extraordinary thing to find it not only intact but intact and in such condition that it could be beautifully, beautifully restored,” she said.

Lobbied for by local historians and supported by the Rensselaer County Legislature, Lewis is the 45th person to be honored in the Postal Service’s Black Heritage series. The Edmonia Lewis stamp is what’s called a forever stamp, meaning it will always be worth the value of mailing a 1-ounce First-Class letter.

For those who have studied and stewarded Lewis’ work, this recognition is long overdue.

“She had been overlooked for so long,” Lemmey said. “To have these physical examples through her sculpture that does survive as evidence for what she did in her time and how highly she was regarded gives us a chance to think not only about her accomplishments but reminds us that we probably overlooked many other people as well.”