WASHINGTON — Experts say electronic voting machines pose a threat to the security of American elections, but Congress has shown little interest in requiring more secure machines nationwide despite Russian hacking in the 2016 and 2018 elections. The states that have relied on the machines, though, are moving to back them up with paper records or replace them outright before the 2020 elections.

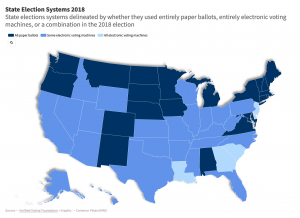

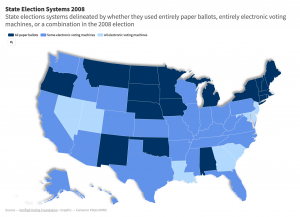

Democratic Rep. Matt Cartwright, who labeled the machines — called DREs —a “clear and present danger,” said that in his home state of Pennsylvania, 83 percent of voters use direct-recording electronic voting machines when they go to the polls. Nationally, 24 states used at least some DREs in the 2018 midterm elections in addition to paper ballots, and five states used them exclusively. The remaining 21 states relied entirely on paper ballots, according to data from the Verified Voting Foundation.

According to University of Michigan computer science professor J. Alex Halderman, the machines are “particularly vulnerable” to hacking and interference by foreign actors, and he should know: he’s hacked them himself.

“My colleagues and I have hacked them, repeatedly,” Halderman told a Senate Select Committee on Intelligence in June 2017. “We’ve created attacks that can spread from machine to machine like a computer virus and silently change election outcomes.”

There are lots of ways to make an election more secure and resilient, but one of the simplest is to make sure the vote is auditable. The problem, according to Halderman: 11 states do not have auditable ballots.

Of those, four states — Georgia, Louisiana, South Carolina and Delaware — rely not just entirely on electronic voting machines, but on electronic voting machines that don’t produce an audit trail. A fifth state, New Jersey, also relies DREs but in some cases uses a voter-verified paper audit trail system.

“Anyone who wants to advance an electoral system that has no non-electronic records is just nonsensical, frankly,” said Paul Rosenzweig, a senior fellow for cybersecurity at the R Street Institute.

He calls paper records a “mandatory minimum” when it comes to election security.

“There has to be an external way of checking that the system has not been manipulated, otherwise there’s no way of checking that the system has not been manipulated. That’s period, full stop,” Rosenzweig said.

According to Rosenzweig, paper records and a type of post-election audit called a risk-limiting audit are consensus priorities for “almost everybody” when it comes to improving election security.

Richard Andres, a professor of national security strategy at the National War College and member of the American Enterprise Institute Global Internet Strategy Advisory Board, agrees that paper could be central to election resilience in a worst-case cyberattack.

“A really serious attack on the integrity of the election, which [Russia] probably could accomplish if they wanted to, would require paper ballots to recover from,” he said. “If you can go back and you can actually physically count ballots, that’s a way to assure the American people that you will never be able to do digitally.”

Andres says that Congress should take up the issue of paper voting records. It’s an idea that’s been proposed before, but like a battery of other federal election security efforts, it’s getting nowhere fast.

Most recently, it was introduced by House Democrats as part of the For The People Act, H.R.1. The bill passed the House earlier this month, but is unlikely to make headway in the Senate.

The idea also was put forth by Reps. Earl Blumenauer, D-Ore., and Bennie Thompson, D-Miss., and Sen. Ron Wyden, D-Ore., who introduced bills to mandate paper ballots in the 115th Congress.

In addition to mandating paper ballots, the Wyden bill would have made risk-limiting audits, which Halderman listed as his top priority after replacing paperless voting machines, compulsory.

According to a Center for Strategic and International Studies report, despite a dearth of federal legislation many states are moving in the right direction as the 2020 election approaches. It says that, in 2020, 38 states will be using either paper ballots or electronic machines with a voter-verified paper audit trail, and six more will be in the process of implementing a voter-verified paper audit trail.

Even Georgia, which William Carter, deputy director of the CSIS technology policy program, called one of the “usual suspects” when it comes to election security flaws and is currently being sued for problems during the 2018 midterm elections, has made progress. In January, the state legislature passed a bill that dedicates $150 million to purchasing voting machines that print paper ballots.

Some states lack the funding to follow Georgia’s lead, however.

Illinois, which in 2016 saw Russian hackers gain access to its voter database, is one such state. Steven Sandvoss, the executive director of the Illinois State Board of Elections, described the state’s voting machines as “ancient” and in need of replacement in a committee hearing last month. However, he said, “with the current budget situation, money is probably not going to be forthcoming any time soon.”

That means that not all of the election security problems from the last two years will be fixed in 2020. Several states, including Texas, Tennessee, Mississippi and Indiana, still have no plans to implement a voter-verified paper audit trail system and will remain paperless in 2020. However, progress has been made.

“A lot of work has actually been done to improve the security of voting machines and voting infrastructure in the last few years as awareness of election security threats has grown and that’s where the attention of defenders is focused,” Carter said.

And according to Rosenzweig, achieving a secure election system is possible. “It’s the same as any other infrastructure system,” he said. “We’ve been doing it in the electric grid for 20 years. We just need to do it in this system.”