WASHINGTON — Before Mia Davis created tabú, she rarely talked about sex.

Her abstinence-only sex education and conservative Midwestern family’s values made it uncomfortable talking about her heavy, irregular period and chronic pelvic pain, let alone the fact that she was sexually active. After an experience with sexual trauma in college left her unable to have sex, Davis felt she couldn’t talk about intimate issues with anyone.

“That experience really impacted my mental health,” she said. “It started to make me feel insecure and impacted my self-esteem and my relationship with my body.”

Wanting to create a way to make conversations about sex less awkward, Davis founded tabú, a blog that provides information and resources about sex, relationships, body and mental health issues. Users can access information on topics ranging from body image and consent to sexually transmitted diseases and masturbation.

“I saw this gap in the market for a safe place for conversations, making these things relatable and having a trusted resource,” she said.

Tabú is part of a steady push toward artificial intelligence and online programs as a means of sexual education. Last year, the sexual health advocacy group Advocates for Youth introduced Mursion virtual classroom, offering teachers sex ed training through student avatars. Last month, Planned Parenthood launched the chatbot Roo that answers anonymous questions about sexual and reproductive health.

The growing application of technology in the sexual education field is a product of people’s desire for instant answers but, more importantly, says Nora Gelperin, director of sexuality education and training at Advocates for Youth, it is a product of failed in-classroom sex education in U.S. schools.

“Young people deserve to know about their bodies, to know how to have healthy relationships and know that their sexuality is normal,” she said. “If they’re not going to get this at school, and we know parents struggle with what and when to say something, then we should present an alternative.”

But Gelperin argues that while technology has the potential to fill gaps in basic sex knowledge left by school health courses, apps and AI should complement rather than replace in-classroom sex ed. The ultimate goal, she says, is to create a comprehensive, unified sex ed system.

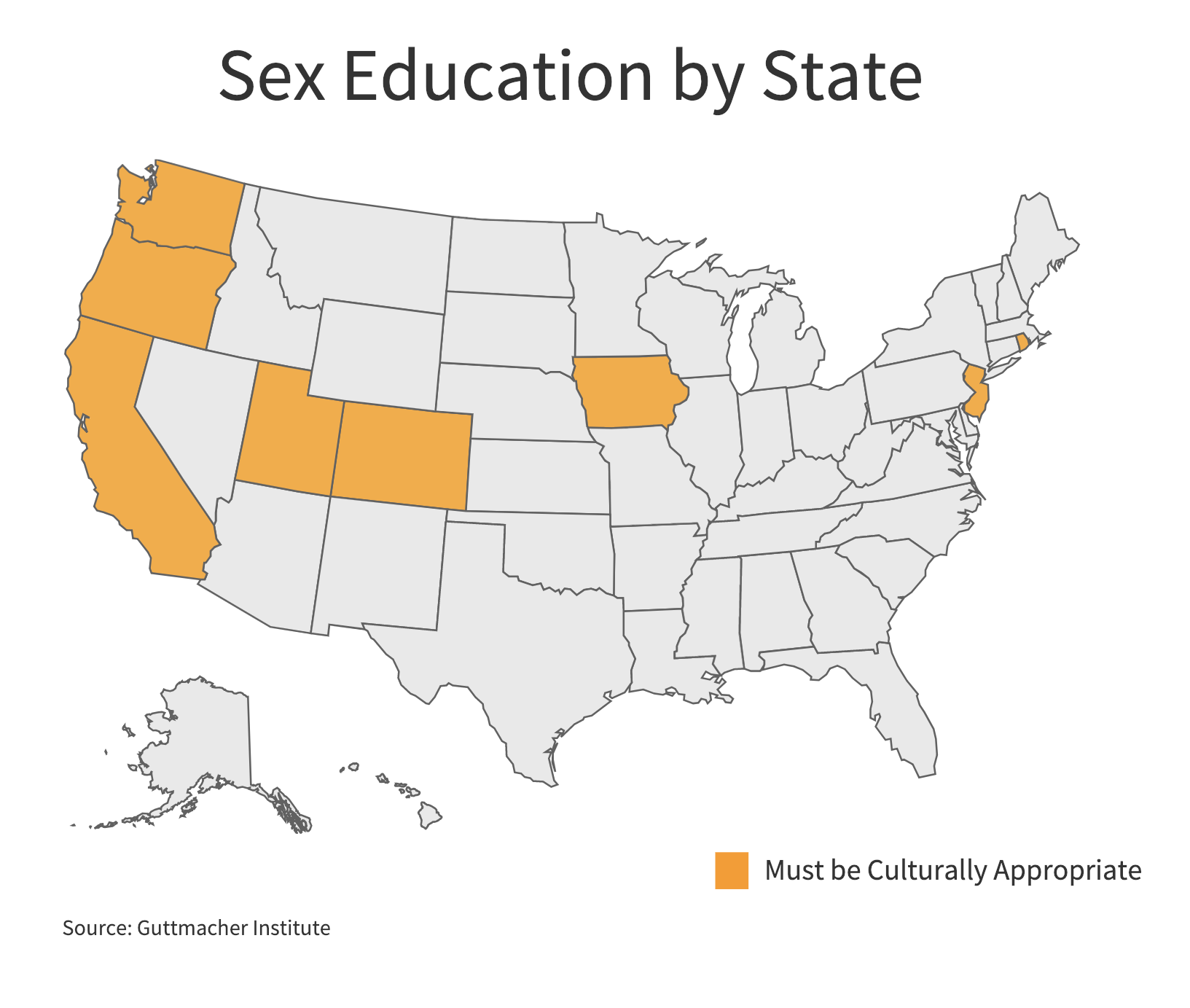

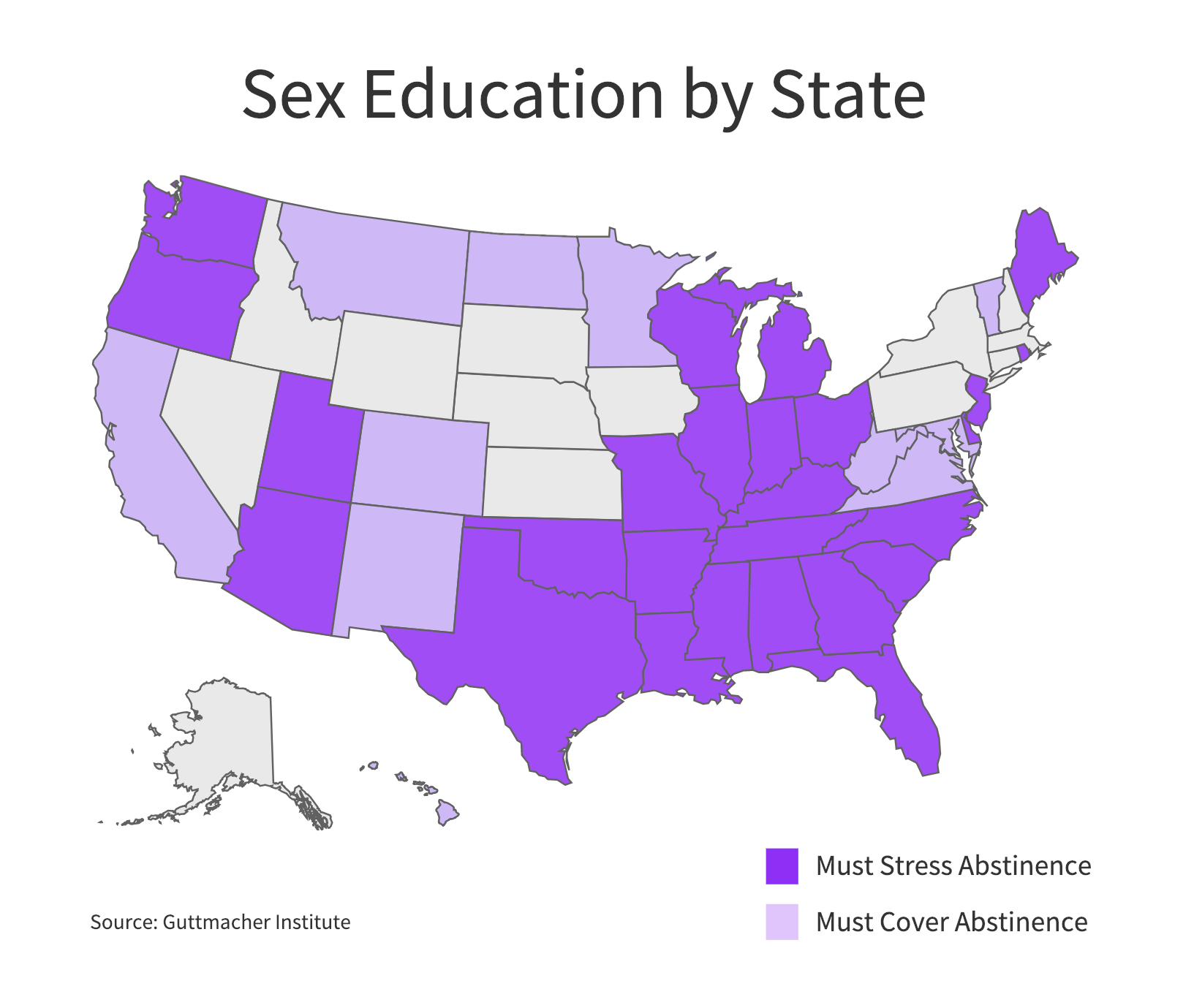

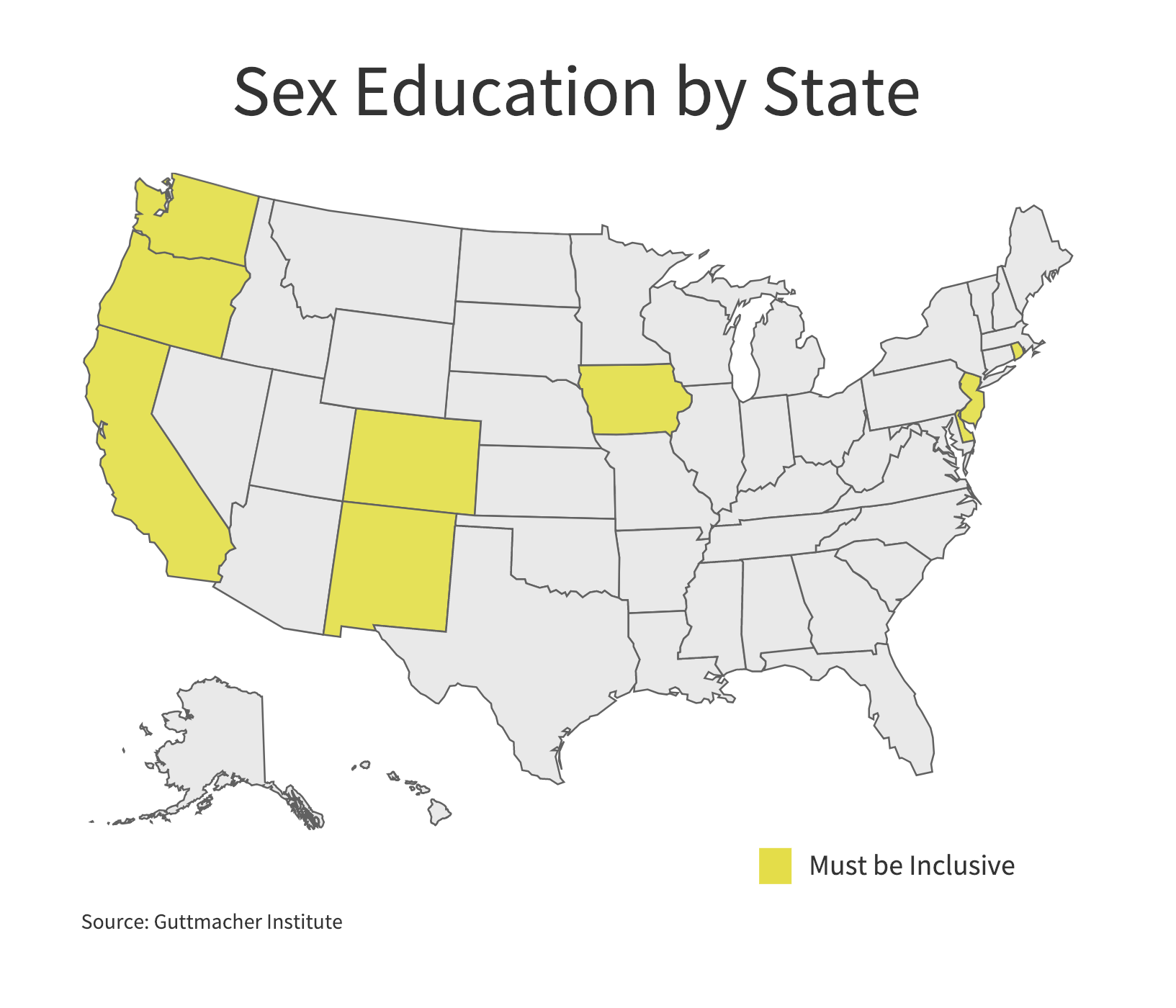

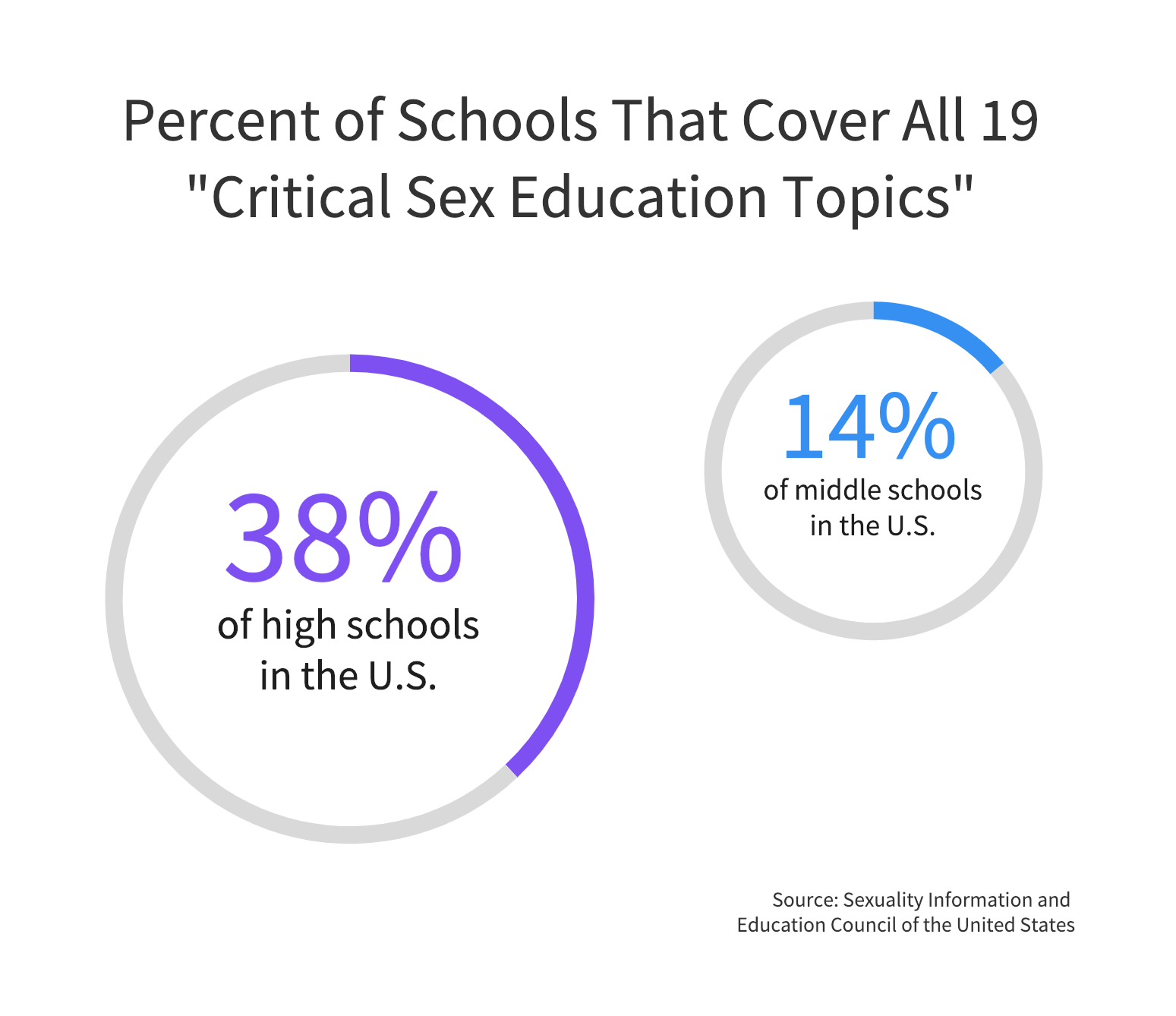

Doing so means tackling the biggest problems with school programs, which, according to Sexuality Information and Education Council State Policy Director Jennifer Driver, are the fragmentation of curricula by state as well as the medical inaccuracy and lack of cultural responsiveness of the information being taught.

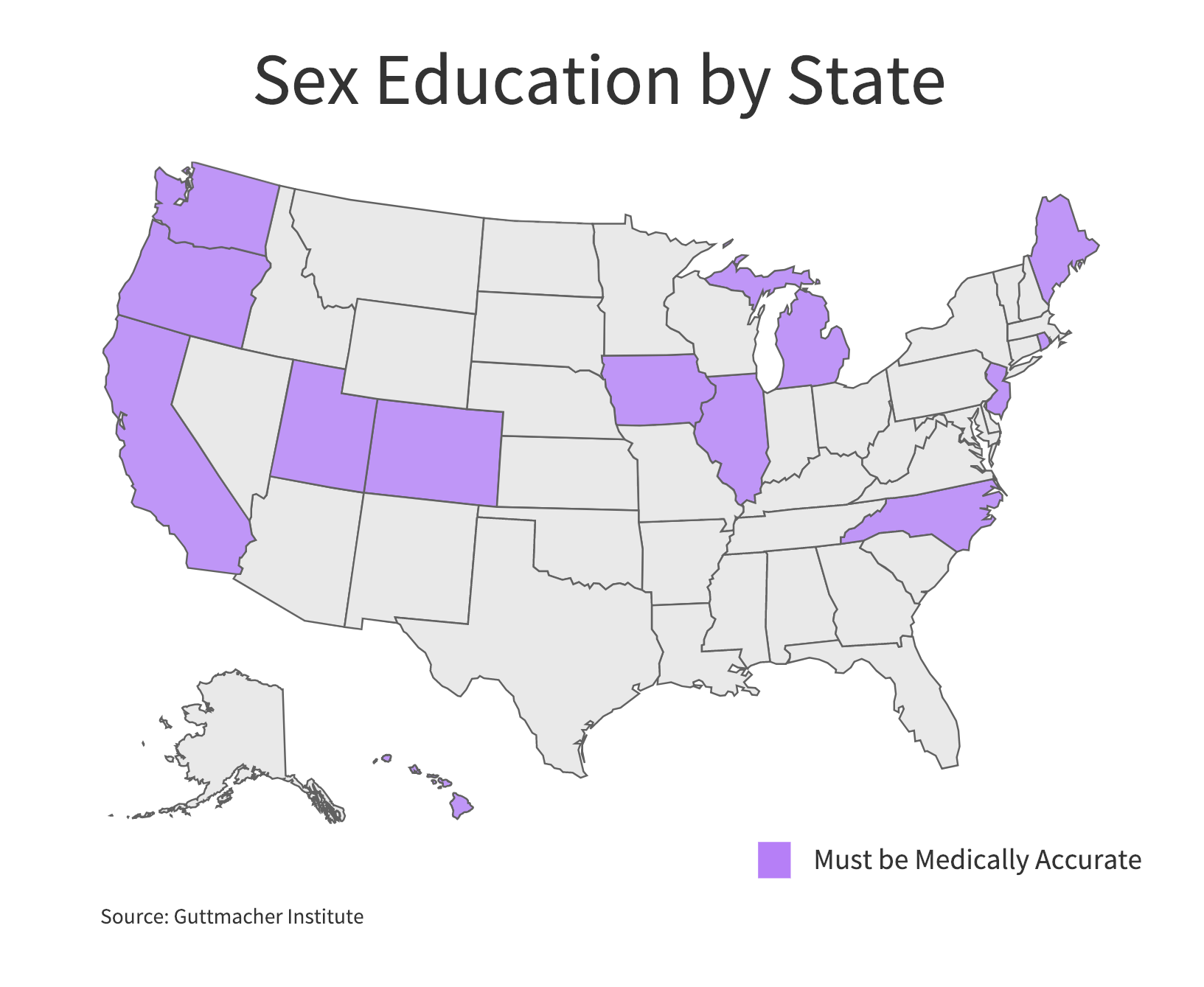

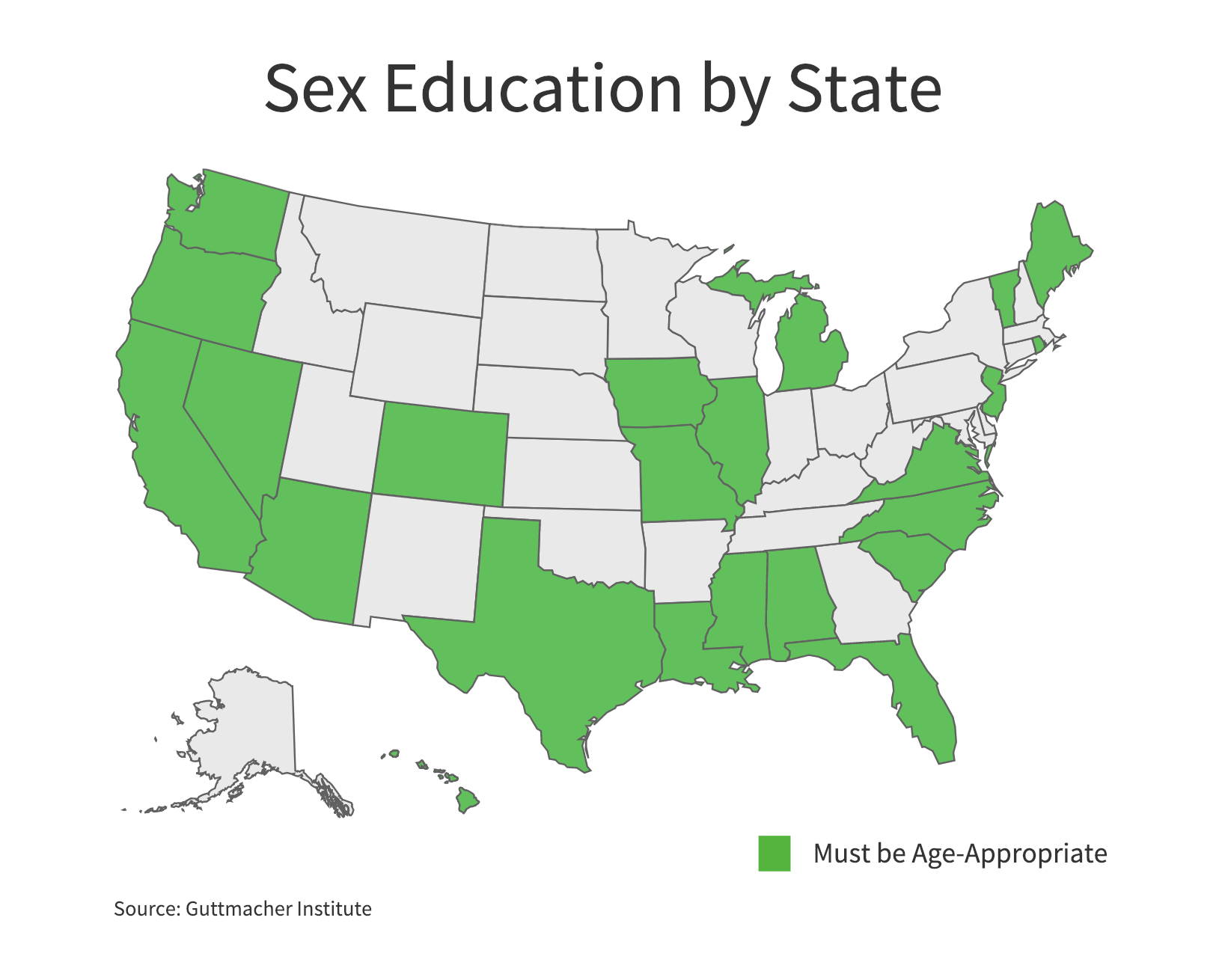

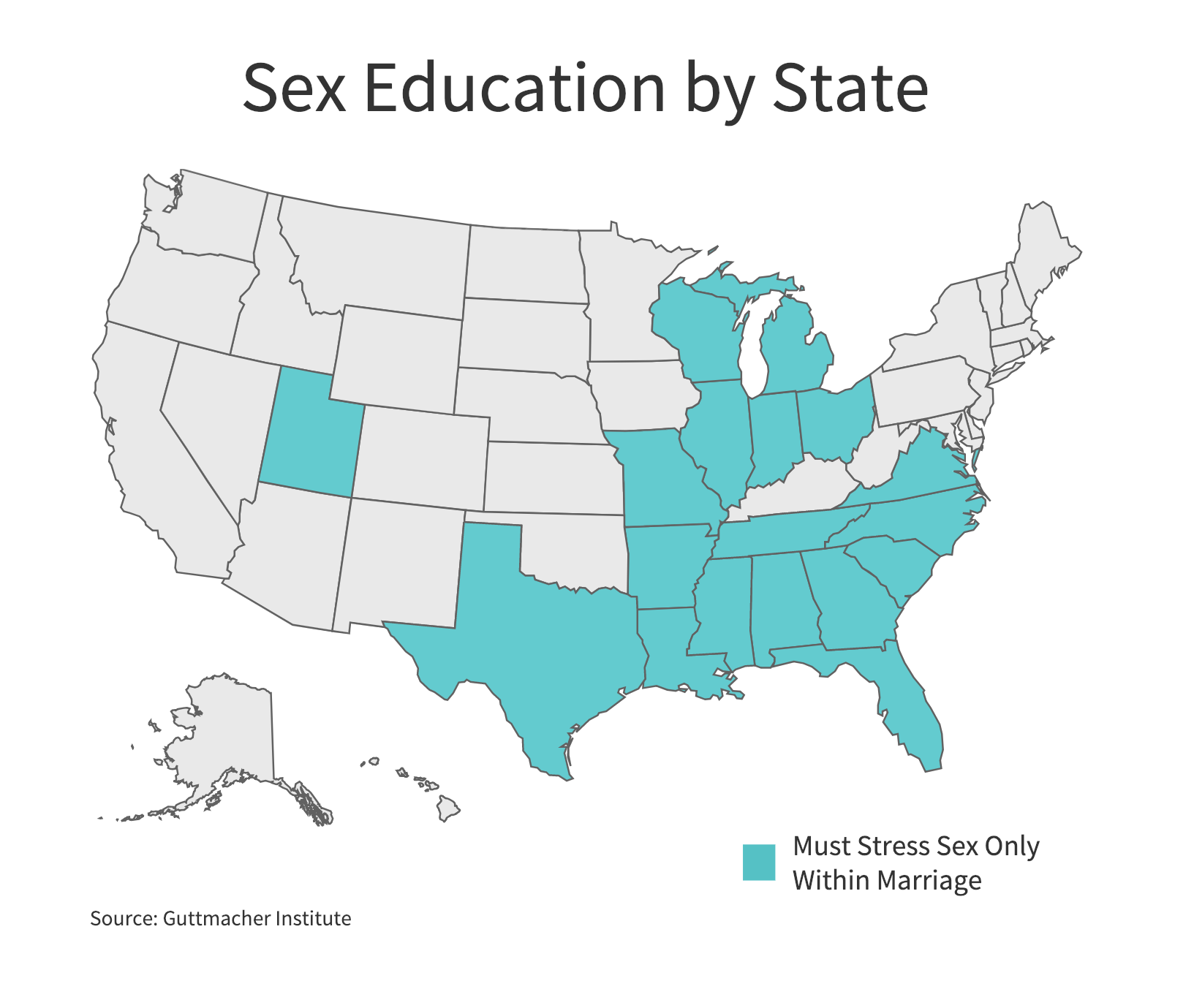

A 2019 Guttmacher Institute report found that only 24 states and the District of Columbia mandate sex ed in public schools, and only 13 states require that the information being taught be medically accurate.

The variation in course content or absence of sex ed courses entirely means young people are vulnerable to misinformation when they seek answers to their questions elsewhere. For many, porn has become their main source of sex education.

“While there’s nothing inherently wrong with porn-viewing, it’s important that people know that it’s entertainment, not education,” Davis said. “But because they’re not getting this education anywhere else, they’re interpreting the unrealistic behaviors in porn as normal in real life.”

Lack of quality information at school also means adolescents are uninformed not only about sex but about the physical, mental and cultural issues that often go hand in hand with sexual and reproductive health.

“Sex ed isn’t just about sex,” Davis said. “It really is about boundaries and healthy relationships and communication.”

Driver thinks it goes even further than that. She argues that sex ed can act as a vehicle for social change because it implicates topics like racial justice, gender equity and LGBTQ rights. So when in-classroom programs are not both medically up-to-date and culturally responsive, students can feel alienated.

This is where technology comes in. By connecting people to others who have had shared experiences — for example, bringing together sexual minorities or survivors of sexual trauma — apps and online programs can affirm people’s identities and provide a sense of community in ways that in-classroom programs generally cannot.

This connective aspect enables technology-based sex education resources to extend beyond adolescence to adults as well. Brianna Rader, co-founder and CEO of Juicebox, a sexual health app and blog targeting adults, believes in what she calls “lifelong sex ed” that adapts to people’s changing needs as they age. She envisions a far-reaching system that begins in kindergarten, teaching children how to say no and respect when others say no, and continues far into adulthood, taking into account hormonal changes, childbirth and menopause.

“These issues are hard for everyone,” Rader said. “Our sex lives and intimate relationships have a huge impact on our well-being and our happiness. But sex and relationships are not innate skills. Just like all other life skills, we deserve education and guidance as we grow and change.”

Gelperin agrees that sex ed should not begin or end at a certain age and should not be limited to public school classes or online blogs. She believes instead in a comprehensive system that leverages the strengths of each forum to make sexual education accessible to all.

“Sexuality is a part of who we are, birth to death,” Gelperin said. “Sexuality education teaches us how to have healthy, loving relationships. It has the potential to not only be life-saving but also transformational, and people everywhere deserve and have a right to this information.”