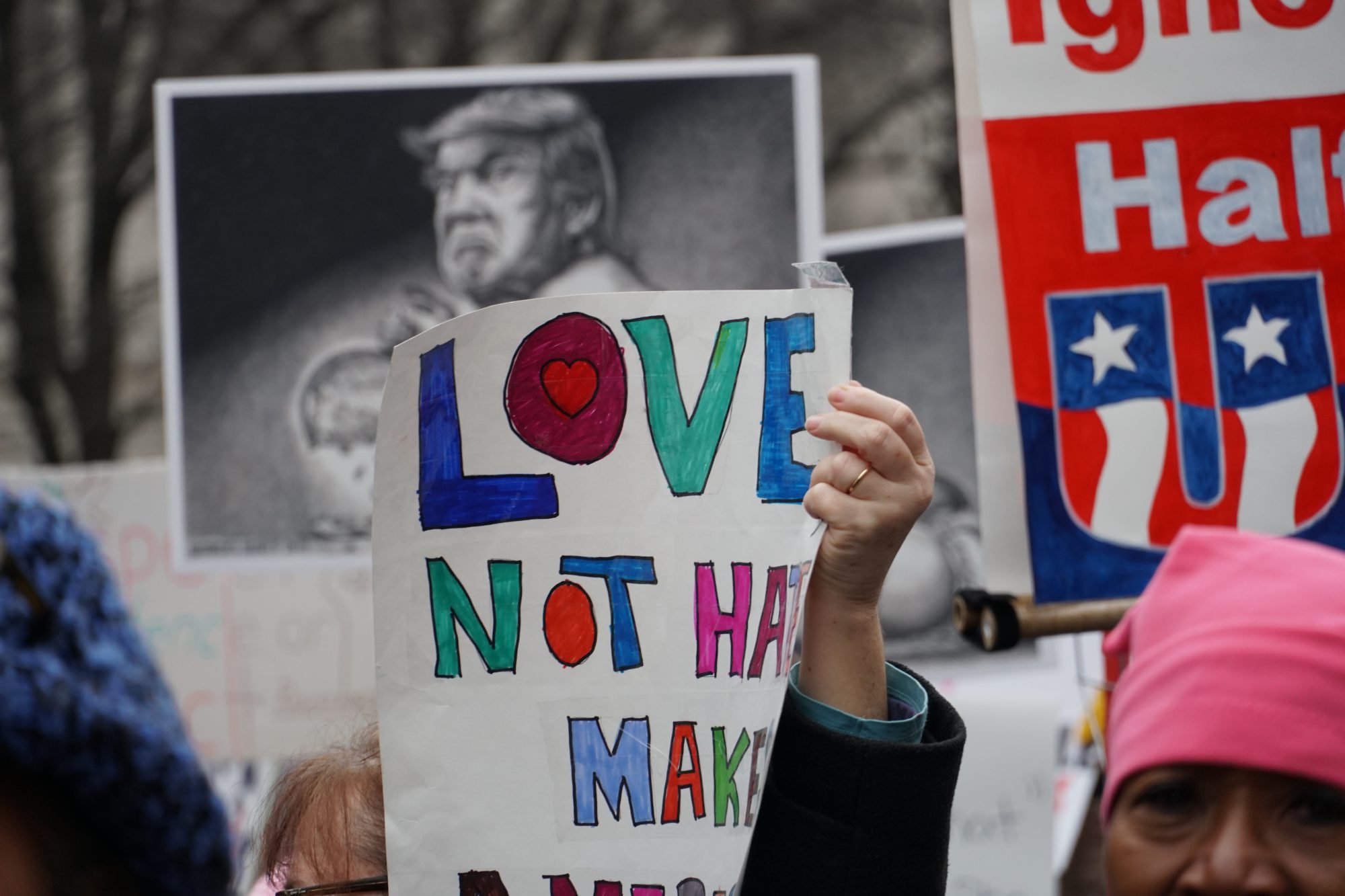

WASHINGTON — Two marches brought tens of thousands of women to Washington this weekend in support of diametrically opposed causes. The one thing in common? Both were controversial.

At the 46th annual March for Life on Friday, a video of students in “Make America Great Again” gear who seemed to mock a Native American elder went viral, prompting accusations that the anti-abortion marchers promoted racism. On Saturday, the third annual Women’s March took place amid claims of anti-Semitism following reports of Co-Chair Tamika Mallory’s relationship with virulent anti-Semite Louis Farrakhan.

“Movements are messy,” said the Rev. Jacqueline J. Lewis at the Women’s March.

And messy is a fitting term for the accusations that have been leveled against the movement. In its three-year history, the organization has grappled with internal divisions, from longstanding concerns over elitism and lack of racial diversity to current accusations of anti-Semitism after Women’s March National Co-Chairs Mallory and Carmen Perez allegedly made anti-Semitic remarks at a leadership meeting in 2017.

Mallory was criticized for her ties to Farrakhan, leader of the religious group Nation of Islam and prominent anti-Semite. The situation was made worse when she refused to condemn Farrakhan in an interview on ‘The View” last week. Less than 24 hours after the interview, the Democratic National Committee dropped its sponsorship of the Women’s March, joining a list of liberal groups including the Southern Poverty Law Center and Emily’s List that withdrew as event partners.

The March for Life has also become the subject of controversy after the video showing a tense encounter between a Native American man and a group of students at Covington Catholic High School in Kentucky who appear to be mocking him.

But as conflicting narratives and longer videos of the incident have emerged, what was initially deemed disrespectful and racist behavior by the boys has become less clear. New video footage shows a group of black men, members of the Hebrew Israelites, shouting vulgar language at the students, passerby and participants of the Indigenous Peoples’ March, which also took place Friday.

The students later began what one teen said were “school spirit chants” to counter the men. However, the woman who shot the initial video said the boys were chanting Trump slogans like “Build the wall” and “Trump 2020,” according to CNN.

Nathan Phillips, the Native American man, arrived soon thereafter, beating a ceremonial drum in what he said was an attempt to diffuse the situation. Instead, the boys circled around Phillips, producing the confrontation that was captured in the viral video.

Covington Catholic High School issued an apology to Phillips and march participants, saying the incident “has tainted the entire witness of the March for Life.” March for Life itself initially addressed the matter in a Twitter post that read, “Such behavior is not welcome at the March for Life and never will be,” but after recent developments, said the organization would refrain from further comment “until the truth is understood.”

But because March for Life participants are largely united in their loyalty to President Donald Trump, the video controversy may not have the same internally disruptive effect that Mallory’s relationship to Farrakhan and previous disputes have had for the Women’s March.

Complaints of elitism and lack of racial diversity since the Women’s Marches began two years ago have caused some women to have second thoughts about their support for the organization, non-white women in particular.

Earlier this month, a Women’s March group in California canceled a rally over objections that participants would be “overwhelmingly white.” Local organizers decided instead to “take time for more outreach,” according to a post on the group’s Facebook page.

These concerns, in conjunction with the recent anti-Semitism claims, may have discouraged people from participating in Saturday’s March, which had a lower turnout than in previous years. Darlene Moreno, 26, a community organizer at the South Bay Center for Counseling in Los Angeles, said she was “definitely turned off” by Mallory’s support of Farrakhan but decided to make the trip to Washington anyway.

“I don’t want this march to be about the directors,” she said. “I want it to be about us, the people. It’s our march.”

Mallory herself addressed the accusations at the march, suggesting they were mischaracterizations by the media.

“No matter what they say, no matter what they write, I will not bend,” she said. “No media outlet and no one else will tell you, I’m telling you, I love all people. And no one will define for me who I am. Only I can do that.”

Other organizers called for unity and forgiveness. After Mallory’s speech, Co-Chair Linda Sarsour told the crowd, “There are no perfect leaders. We are all flawed human beings. We should not be throwing stones from glass houses.”

Ultimately, what unified marchers was resistance to what Lewis called the “common enemies” of white supremacy, transphobia, sexism and greed — and, to a great extent, Trump.

The Trump administration’s handling of reproductive health care issues in particular motivated some women, like 76-year-old Rosemary Codding. Codding, who owns Falls Church Healthcare Center in Virginia, said she was most upset that “there is no interest in women’s health by this administration.”

In a telephone interview, Cindy Romero, spokeswoman for Catholics for Choice, more explicitly criticized Trump’s efforts to strengthen restrictions on funding for abortion and access to no-cost contraception.

“The Trump administration has weaponized religious freedom to lift up the views of a minority of anti-choice, extremist Catholics … to impose their version of morality on everyone else through law and through policy,” she said.

Those participating in Friday’s March for Life, however, were enthusiastic about Trump’s anti-abortion policies. Organizers and marchers praised his proposal to codify the Hyde Amendment, which forbids federal funding of abortion services, and his reinstatement and expansion of the Mexico City Policy, which blocks federal funding of abortion services outside the U.S.

Trump has endorsed the March for Life and last year became the first sitting president in the organization’s history to address the march in a live video.

This year, he again appeared in a recorded video shown at the event, in which he promised to veto any legislation “that weakens the protection of human life.” Speaking in person, Vice President Mike Pence described Trump as “the most pro-life president in American history” and told the crowd, “You have an unwavering ally in this vice president, in our family, and you have a champion in the President of the United States of America.”

For many of those opposed to abortion, having a “champion” in the White House is critical to tackling “the biggest civil rights issue that we’ve faced since the ‘60s and ‘70s,” according to Debra Burchfield, Executive Director of Hope of the Delta, a pregnancy clinic in Pine Bluff, Arkansas.

Burchfield, who participated in Friday’s March for Life, said that although she is not optimistic that Congress will pass anti-abortion legislation, she thinks Trump has done “an amazing job.”

While participants of both the Women’s March and March for Life expressed a desire for bipartisan policies on women’s access to contraception and abortion services, many said they doubted Congress would actually adopt such legislation. In this regard, marchers on either side were united in their anger at the partisanship in Washington.

These same marchers’ anger, however, fell along party lines. Anti-abortion marchers were more likely to blame the Democratic-controlled House, while the women’s rights marchers were more likely to blame the Republican-controlled Senate and President Donald Trump.

“Right now, I’m a little bit upset with Congress, not with our president, but with Congress,” said Joan Abruzzo, a stay-at-home mom from Baltimore, Maryland and participant in the March for Life. Abruzzo said she thinks the Senate is “working fine,” but the House “has some problems.”

Lynn Gerson, a litigation manager from San Diego who participated in the Women’s March, said, “We need to leave a good footprint in the sand” for future generations but worries that will not be possible “until we change the Senate.”