WASHINGTON –Democrats on Wednesday proposed spending $100 billion over 10 years to build new schools and improve existing schools nationwide, especially in low-income communities.

Sen. Jack Reed, D-R.I., who sponsored the Senate version of the bill, called on the Trump administration to “address a truly national emergency” by supporting the legislation.

Reed, whose father was a school custodian, said his father worked hard to “keep schools safe and clean for the kids.”

“There is a whole generation of people doing that but it’s harder because these buildings are 45 years old,” he said. “They haven’t been maintained as well as they should have been.”

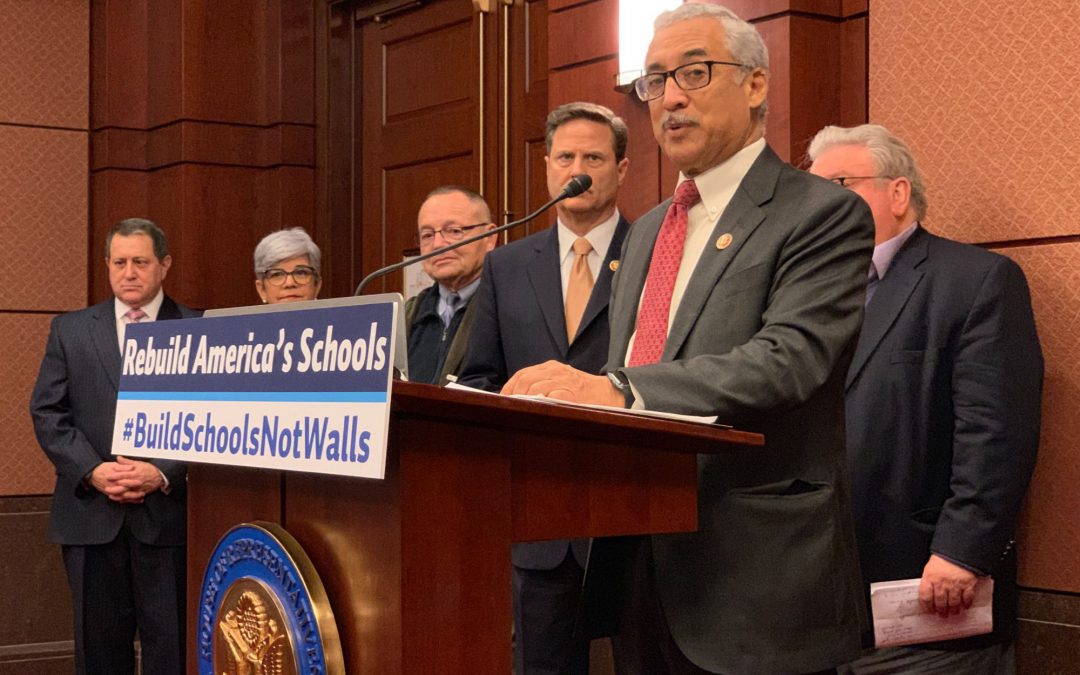

The bill, which has 153 co-sponsors, is one of the major items on the agenda of the House Education and Labor Committee, according to Rep. Bobby Scott, D-Va., the chairman of the committee.

A 2016 State of Our Schools Report published by the 21st Century School Fund, National Council on School Facilities, and The Center for Green Schools found an annual state and local spending gap of $46 billion on school facilities.

“The average age of a school building is 50 years old,” said Lily Eskelsen García, president of the National Education Association, the largest teachers’ union in the U.S. “Neglected buildings and infrastructure are making our students and educators sick. It takes money to fix a sick building.”

The proposal would specifically target low-income schools through a $70 billion grant program and a $30 billion tax credit bond program. According to a 2018 report from The Education Trust,

school districts that serve large populations of students of color and low-income families receive far less funding than their white, affluent counterparts.

“Some kids in low-income schools don’t have access to high speed internet,” said García. “It’s something we must address.”

Along with this infrastructure investment, federal, state, and local resources would be leveraged to expand access to high-speed broadband and develop a national database on the current condition of public schools. The legislation also requires that the Government Accountability Office to report within two years on projects that have been completed.

“We have to develop the intellectual capital to deal with these technologies that are coming along so rapidly. That begins in elementary schools with (science, technology, engineering and math) training,” said Reed. “If the schools are inadequate and laboratories don’t exist, we will never stay ahead. In fact, we will fall behind.”

In a December 2018 poll conducted by POLITICO and Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health, over 65 percent of Democrats and Republicans said increasing K-12 funding is an “extremely important priority” for the 116th Congress. Currently, the federal government only covers school repair costs in cases of disasters.

The House Democrats sponsored a similar bill in the last Congress that failed to pass in the GOP-controlled House. This year, opposition remains from House Republicans.

“This proposed legislation distracts from the limited and important role the federal government does have in supporting disadvantaged students’ education in the classroom,” said a spokesman for the Republicans on the House Committee on Education and Labor. “What’s more, it attaches federal mandates that would increase costs to taxpayers and make it harder for schools to meet their communities’ needs.”

However, Reed and Scott said they expect bipartisan support both in the House and Senate.

“There is common recognition of the problem and I’m confident we will get the support,” said Reed.

If there is a broader infrastructure spending bill introduced in the House, the legislation could “easily be part of it,” according to Scott.

James Boland, president of the International Union of Bricklayers and Allied Craftworkers, said the funding would help schools while also providing jobs.

For teachers, the funding would come as a welcome sign of support at a time when teacher protests are springing up across the country.

“We are seeing what is happening in California and West Virginia,” said Grichelle Toledo Correa, an elementary school teacher in Puerto Rico who advocates for public schools. “What are we saying to kids if we send them to these schools in poor conditions? Our country is better than that.”