WASHINGTON – Despite early concerns about its effects on reproductive health care in the developing world, Congress is unlikely to repeal policy that restricts international organizations’ ability to offer abortion services if they receive U.S. funding, Sen. Jeanne Shaheen, D-N.H., said Thursday.

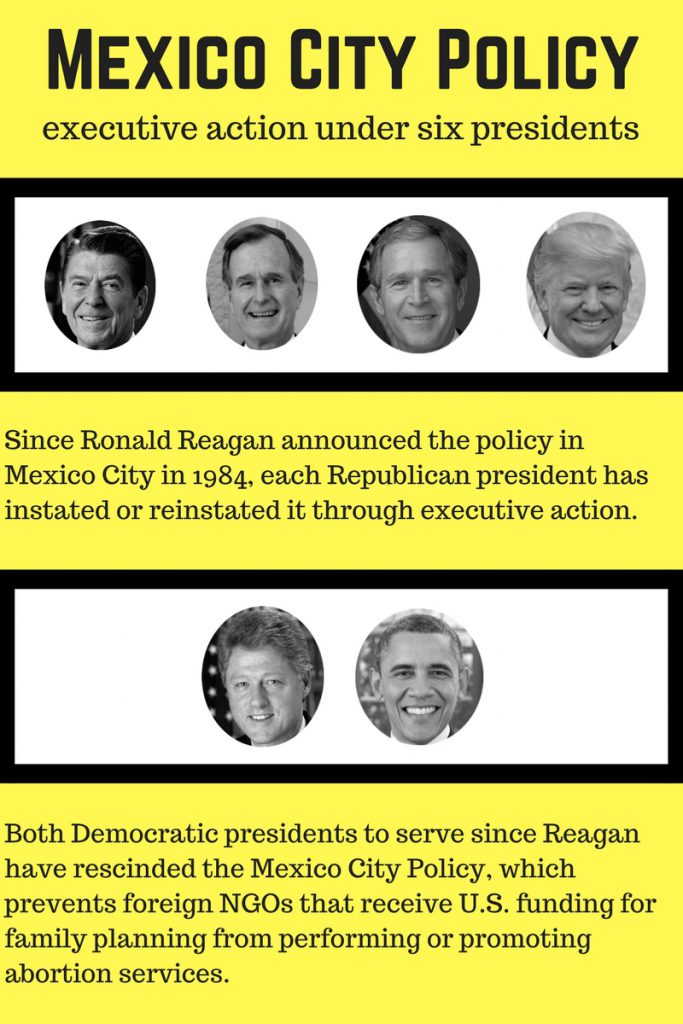

According to Human Rights Watch, the U.S. spends approximately $575 million on family planning and an estimated $8.8 billion in total on global health. Under previous Republican presidents, the “Mexico City Policy” or “Global Gag Rule” blocked non-governmental organizations (NGOs) from receiving U.S. family planning funds. Reinstated under President Donald Trump, the policy now encompasses groups receiving any type of U.S. global health assistance.

“This puts at risk 15 times more funding and millions more women and families,” Shaheen said, speaking at an event hosted by the Center for American Progress. The Trump administration’s move, she added, targets some of the most effective health organizations across the world. “Without funding, these organizations won’t be able to provide HIV services, maternal health care or even counsel woman on the risks of things like the Zika virus,” she said.

But since its implementation, the Trump administration has touted the policy to anti-abortion voters as a conservative achievement. “From his first day in office he’s been keeping his promises to the American people,” Vice President Mike Pence told the March for Life last year.

While the on-again, off-again Mexico City Policy has long jeopardized reproductive health organizations, experts said that the expanded restrictions have challenged a wider set of NGOs.

Groups often form partnerships on the ground to offer more comprehensive services, but industry leaders like Suzanne Ehlers, president and CEO of PAI, a reproductive health advocacy group, say that coordination and communication has dwindled as NGOs consider their need for U.S. funding.

“This policy targets the most effective health organizations that actually have the capacity to be a hub for all of these partners to come together,” said Lisa Schechtman, the director of policy and advocacy at WaterAid America. Although WaterAid focuses on providing safe drinking water, sanitation and hygiene services, it often works with maternal health organizations that have been affected by U.S. restrictions. Schechtman said many are concerned the partnerships could fall through.

“One of the challenges that we still face is confusion around how things are going to be implemented,” said Anu Kumar, interim CEO at Ipas, a global nonprofit group. “The confusion and the fear is leading people to act in this way.”

Emma Nilsson, who works on development issues for the Embassy of Sweden, said that the U.S.-NGO relationship is not the only one at stake as a result of Trump’s policy shift. Although the United States is the top financer of global health initiatives, it often works closely with other countries to implement aid. According to Nilsson, the Mexico City Policy has restricted what Sweden can do as a U.S. partner, and it may be forced to stop funding NGOs that comply with Trump’s restrictions due to ideological concerns.

To combat these funding rollbacks and their impact on women’s health, Shaheen introduced a bill to repeal the Mexico City Policy, but she said working with lawmakers across the aisle could be difficult. In 2017, Sen. Mike Lee, R-Utah, introduced legislation that would make the policy permanent, later praising Trump for his decision to “protect life in foreign assistance.”

“We have had the benefit of having support from Sens. Susan Collins and Lisa Murkowski, both Republicans,” Shaheen said of her bill’s prospects. “Sadly, they have been the only Republicans who have been supportive, so I’m not optimistic that we’re going to see anything happen in this legislative session.”