CARY, N.C. — It’s hard to find empty space in the cozy Democratic field office here, where the walls are adorned with signs promoting Democratic candidates across the ballot and messages of support for presidential nominee Hillary Clinton.

“I’m with her because she’ll fight for me,” reads one slip of paper.

Just four miles down the same road, nestled in a strip mall, the spacious Republican field office in an empty Taekwondo studio feels bare in contrast. With white walls and white floors, it’s eerily reminiscent of a hospital.

These field offices, temporarily set up for the Nov. 8 election, illustrate the vast differences between the ground-game strategies of Clinton and Donald Trump, the Republican presidential nominee.

“We’re ramping up everything,” said Linda Ward, a volunteer at the Democratic field office in this town of about 150,000, just west of Raleigh. “One of it is making sure we knock every door, make every phone call. We’re not leaving any of that to chance, it’s what you call our ground game.”

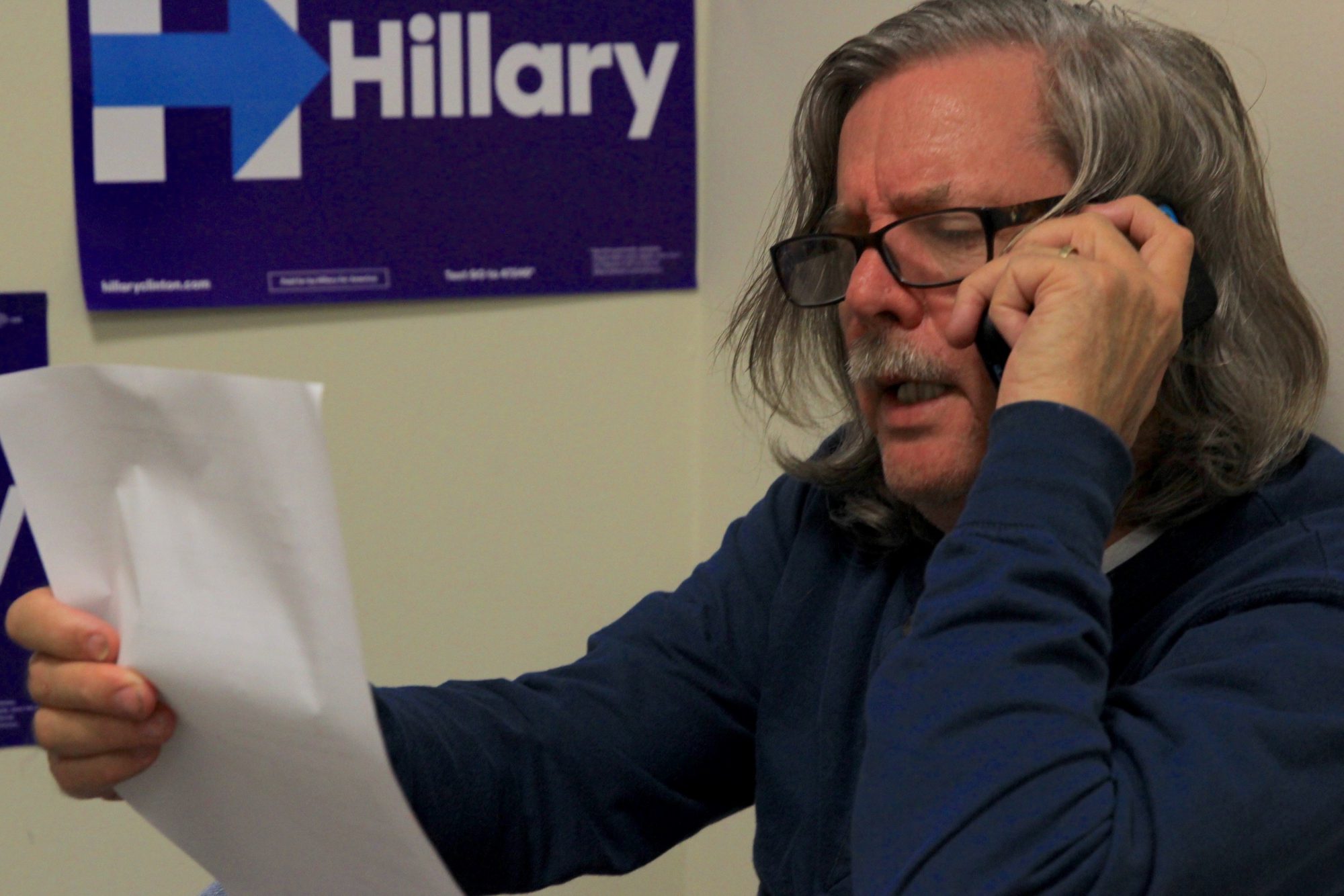

Sam Eskenazi, a 74-year-old New York resident, flew out to Carrboro, North Carolina, two weeks ago to join his daughter as a volunteer for Clinton in the closely contested state. On a recent Wednesday, his shift included phone banking and a couple of hours of canvassing in Durham, making sure to leave enough time to catch the Chicago Cubs in Game 2 of the World Series later that night.

Barack Obama won the state in 2008, using a sophisticated data operation to produce what many political experts consider the gold standard of ground games. He lost it to Republican challenger Mitt Romney in 2012, but since 1956, no Republican has reached the White House without winning the state’s 15 electoral votes, a fact Clinton surrogates have eagerly touted while stumping for her.

She holds a nearly 3-point lead over Trump in the state, according to a RealClearPolitics polling average.

Trump, in a departure from conventional political norms, has almost entirely handed off his campaign’s ground game to the Republican National Committee, relying on the party to manage its boots-on-the-ground voter turnout operation.

For Trump, that could make it more difficult to reach out to North Carolina Republicans who are not already excited by his candidacy, said Katy Harriger, professor and chairwoman of Wake Forest University’s department of politics and international affairs.

“There’s this other group of traditionally Republican voters who aren’t riled up and who are concerned about him, but who might be persuaded if there were a ground game, you know, to get out,” she said. “If he loses, it will be because he failed to do that, to recognize that he needs every Republican identifier to show up.”

In an attempt to capitalize on this concern, the Clinton campaign is using its widespread grassroots base to appeal to disaffected Republicans and independents, said Dan Kanninen, a senior advisor for the campaign in North Carolina, in a conference call Oct. 28. The number of ballots being cast by independents is sharply on the rise in early voting, Kanninen said.

Clinton operates 33 field offices to Trump’s 24, with thousands of volunteer leaders and an additional 40,000 active volunteers. The real-estate mogul has 700 trained organizers leading thousands of volunteers, Kara Carter, the communications director for the RNC in North Carolina, told the Wall Street Journal.

Carter did not respond to multiple requests for comment for this article.

In a Sept. 12 memo, RNC chief strategist and communications director Sean Spicer said the party’s ground game has vastly improved since 2012. The gap in the number of field offices is negligible, he said, equating Clinton’s ground game to a “cubicle factory.”

As Nov. 8 nears, both campaigns are emphasizing early voting, which in 2012 accounted for 60 percent of votes in North Carolina. The flexibility and convenience of early voting allows North Carolinians to cast their ballots anytime within the state’s 17-day period, which began Oct. 20 and ends Saturday.

“The campaign, along with the Republican National Committee, the state party here in North Carolina, are … encouraging folks to come out and vote,” said Marc Lotter, a spokesman for Indiana Gov. Mike Pence, the Republican vice presidential candidate.

Lotter said Pence has advocated for early voting at his rallies so partisans can focus on reaching out to other Republicans and energize them on behalf of Trump and other Republicans on the ballot.

Early voting benefits those who don’t have the time to stand in line on Election Day, such as lower-income workers, a Democratic-leaning voting bloc, said Rogan Kersh, Wake Forest University provost and professor of politics and international affairs.

“Eliminating early voting will typically depress Democratic turnout by a couple percentage points,” Kersh said. “In a very tight race that could make an enormous difference.”

In July, a federal court struck down the state legislature’s 2013 attempt to limit early voting by reducing the number of polling sites and the length of the early voting period.

Last week, 132 additional early voting sites were opened in North Carolina, some in counties that previously only had one site despite having relatively large communities. In the Oct. 28 Clinton campaign conference call, Marlon Marshall, Hillary for America director of states and political engagement, said the new sites have led to turnout rates that have exceeded those seen in 2012.

For example, Guilford County — which had only one voting site prior to Oct. 27 — now has 25 sites and reported that it broke all its records with almost 22,000 ballots cast compared to 15,000 on the biggest day of early voting in 2012.

“As more sites open up across the state, we’re feeling very, very good about turnout, feeling very good about our chances to win the state,” Marshall said.

Early votes, can be misleading. Four years ago, Obama led Romney by 450,000 votes after early voting, but went on to lose the state by just over 2 points.

Still, the Clinton campaign is pushing for early voting, with the nominee herself and popular surrogates, such as actress Angela Bassett and first lady Michelle Obama, making appearances across the state. At these events, the campaign collects contact information and uses that data to encourage more people to volunteer in get out the vote efforts.

In October, a Clinton campaign official said, efforts shifted from making sure supporters were registered voters to creating a plan for how they planned to get to the polls, preferably before Nov. 8.

Peter Sterrett, a 62-year-old Democratic volunteer in Cary, said canvassers try to “drill down a little bit into when, how you’re going to get there, who you’re going to go with, do you know where it is?”

Photo gallery by Rishika Dugyala/MNS and Benjamin Din/MNS

By now, in most battleground states, the campaign’s ground game is focused on converting the contacts it’s had with supporters over the past few months — from phone calls to door knocks — into actual votes.

Those who work the phone banks are calling supporters to make sure they’ve voted and to ask if they’re free to volunteer.

Over the last two weeks, the Clinton campaign in North Carolina has knocked on more than 628,000 doors and made more than 764,000 calls to voters, according to Kanninen.

However, not everyone answers the door or picks up their phone, a fact of life that campaign volunteers have come to terms with.

Back in the Woodcroft area of Durham, Sam Eskenazi spent three hours canvassing early Wednesday afternoon. After an initial string of no responses, he turned and shrugged, mentioning most people were probably at work.

“No car in the driveway is usually a pretty good hint that there’s no one,” he said.

The houses he visits belong to people who are Democrat or lean that way, so Eskenazi said the responses he’s received have been positive, with many people saying they’ve either voted already or are planning to.

Even if no one answers, he said the work he’s doing is still important to help get out the vote.

“It’d be nicer to have them answer, but you’re leaving them a couple of things,” Eskenazi said, holding up a door hanger with early voting sites and a card listing Democratic candidates on the ballot. “Even if you’re not talking to them directly, they’re getting your materials, so it’s all a plus.”

“As long as they vote the right way,” he said. “You know, that’s what counts in the end.”