WASHINGTON — The recently concluded United Nations climate change meeting in Johannesburg created the strongest protections in history for endangered species, according to U.S. wildlife officials and other experts who attended the meeting.

Sharon Guynup of the Wilson Center, an international issues think tank that hosted the discussion, said the world is going through its sixth mass extinction, with the Center for Biological Diversity finding the worst level of species die-offs since the loss of the dinosaurs. Dozens of species are becoming extinct each day, and 30 to 50 percent of all species may be heading towards extinction by 2050, the center said.

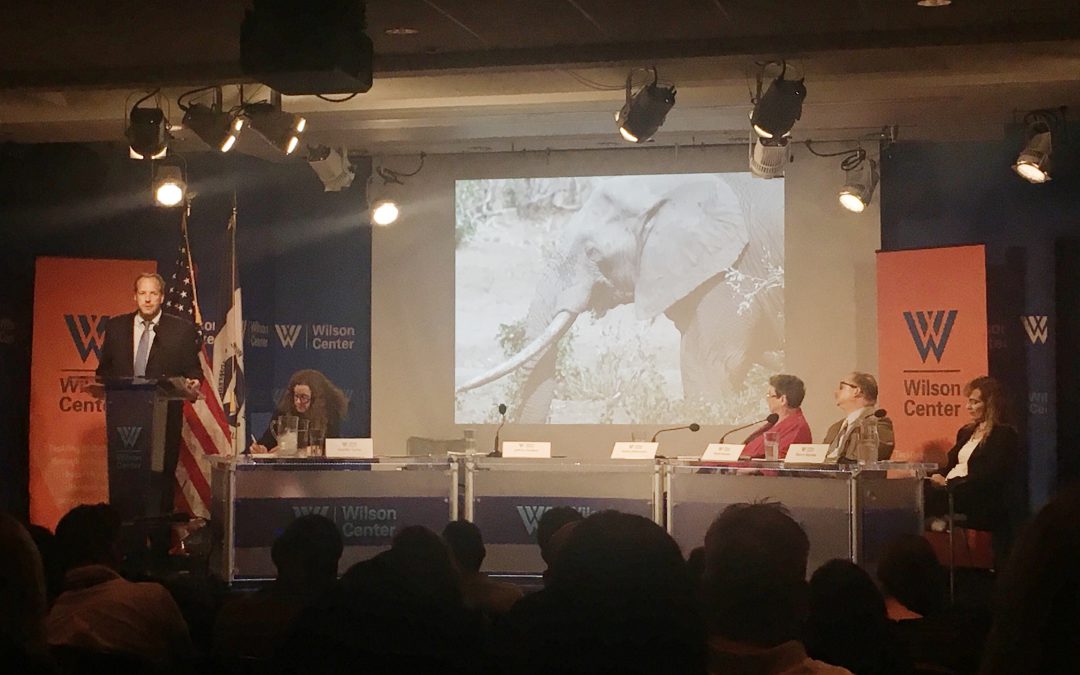

More than 180 parties participated in the UN conference — COP 17’s Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora World Wildlife Conference — making it the largest wildlife trade meeting ever held. The conference increased protections for more than 50 species, including sharks, rosewood trees and devil rays.

The panelists also discussed what they saw as progress in curbing poaching. Guynup said illegal wildlife hunting is one of the fastest growing and most profitable types of organized crime.

COP 17 took important steps to reduce poaching, Guynup said. The conference e strengthened the international ban on trade in ivory and adopted global trade bans for pangolins, which look like scaly anteaters and are indigenous to southeast Asia and sub-Saharan Africa, and African Grey parrots.

The ivory trade ban was aimed at protecting the global elephant population, which has fallen to less than 500,000. More than 100,000 elephants were killed between 2010 and 2012 for their ivory.

Wildlife Conservation Society Vice President Susan Lieberman said science was the main winner at the Johannesburg meeting compared with past meetings, which shied away from tackling tough regulations based on data to avoid mention of corruption in the wildlife trade.

“It was very progressive and collaborative and very science-based,” Bryan Arroyo, assistant director for international affairs at the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, added. “That in itself is a change that is unprecedented.”