WASHINGTON — House Republicans accused the Obama administration of attempting to subvert the law and also congressional authority Wednesday during a hearing on a new law that replaced No Child Left Behind. Democrats charged that Republicans were trying to dismantle federal oversight of education.

“The Department of Education has released a regulatory proposal so unprecedented and so unlawful that it demands its own examination,” said Todd Rokita, R-Ind., chairman of the Education and Workforce’s subcommittee on elementary and secondary education.

At issue is a 45-year-old staple of federal education law called “supplement-not-supplant.”

Congress instituted the provision in 1970 after lawmakers found districts stopped funding low-income schools that received federal aid. Supplement-not-supplant calls for districts to give the same amount of funding to impoverished schools receiving aid as they would otherwise. Democrats have framed the issue as a crucial civil rights matter, but school officials have long complained that the law comes with byzantine regulations preventing them from doing comprehensive change.

In passing the 2015 Every Students Succeeds Act, Republicans say Congress removed many of the regulations around supplement-not-supplant. The rules were supposed to be finalized in spring meetings between lawmakers, school officials and civil rights leaders. But after talks broke down, the Education Department put forward regulations last month laying out several ways districts and states can show they are in accordance with federal law.

The new rules provoked outrage among Republican leaders who say they go far beyond what’s allowed by the law.

“The administration is not allowed to rewrite law.” said John Kline, (R-Minn., chairman of the House Education and the Workforce Committee.

Ohio Rep. Marcia Fudge, top Democrat on the panel, painted the Republican criticism as part of a broader attempt to delegitimize the Obama administration. She claimed that Republicans were trying to erase federal oversight of public schools altogether.

“I can assure you that it was not Congress’s intent to allow compliance for this important requirement to be subject to the whims of over 18,000 school districts,” Fudge said.

Education officials from Nevada and Oklahoma argued the rules would subvert school choice and hurt magnet schools that benefit all students and don’t necessarily fit into the Education Department’s formulas.

But Scott Sargard of the Center for American Progress said without strict regulation, inequities will persist.

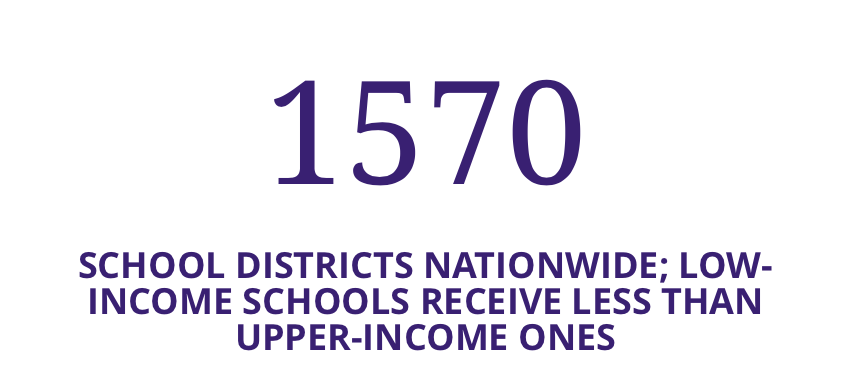

school districts nationwide; low-income schools receive less than upper-income ones

Source: Department of Education

Average fewer dollars per year low-income schools in those districts receive

Those inequities, however, largely come from teacher costs, said Georgetown University professor Nora Gordon. Gordon, an economist who focuses on the federal government’s role in education, told the committee that the Education Department’s rules were not a valid interpretation of the original bill.

She said because there’s higher teacher turnover in high-poverty schools, teachers often don’t accrue the seniority that brings a higher salary. New teachers are less effective she said, but forcing schools to equalize funding can’t fix that.

“I think the problem they’re trying to solve is they want lower teacher turnover in high-poverty schools,” Gordon said in an interview after the hearing. “Which is a problem that should be solved, but not with regulation of supplement-not-supplant.”