How an unregulated, invisible industry makes a fortune on people’s personal information without them even knowing

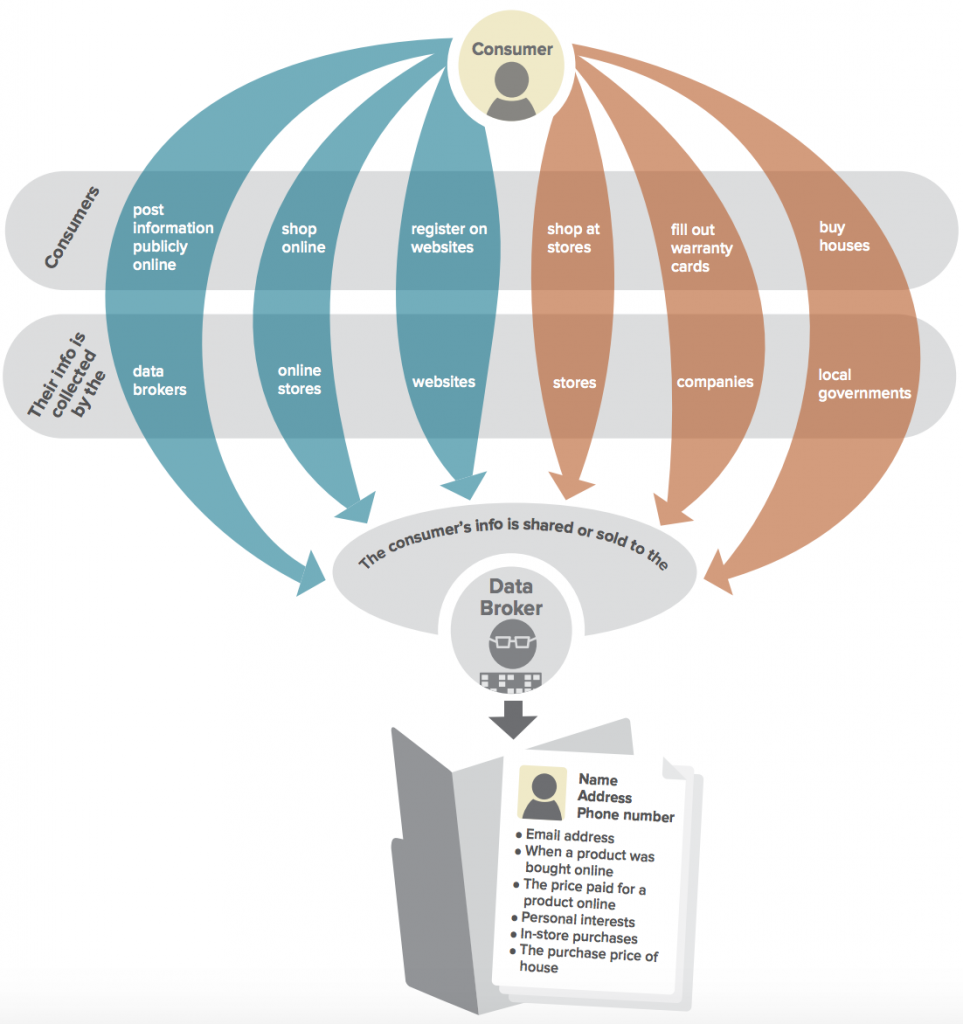

WASHINGTON — Every year, data brokers make billions of dollars collecting and selling your personal information – even sensitive data like Social Security numbers, financial transactions and political affiliations – and you probably don’t know when it happens.

“It’s impossible right now to live without your information and life being touched by a data broker unless you literally put on a tin foil hat and lived in a cave,” said Pam Dixon, the executive director of the World Privacy Forum, a privacy and civil liberties research group.

Though this may seem exaggerated, there’s no denying that the demand for detailed consumer information is growing in all industries globally. Data brokers meet that need by keeping tabs on everything from your credit scores to what you buy at the grocery store.

Unlike government agencies, which collect data for reasons ranging from national security to creating long-term education trends, data brokers are interested in analyzing your information and selling it for a profit.

A 2014 report by the Federal Trade Commission found that data brokers are able to easily create “a detailed composite” of an individual’s life using a wide assortment of information collected from government, online and commercial sources.

Once collected, data is often shared without restriction between brokers and other organizations, including insurance companies, marketing agencies, commercial businesses, the federal government and more.

Acxiom Corporation, one of the companies analyzed in the FTC report, was found to have an average of about 3,000 data points on every consumer in America. Though it’s one of the largest data brokers in the world, Acxiom is just one of what the Federal Trade Commission estimates to be thousands of data collection agencies.

Privacy advocates fear a lack of comprehensive regulation to monitor how brokers collect, store and use their troves of information.

Existing laws can be applied to certain types of data — brokers’ use of individual credit scores is limited by the Fair Credit Reporting Act, and the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act monitors the privacy of health records. Beyond that, brokers are free to scoop up whatever information they can.

According to Tiffany George, an attorney at the FTC who co-wrote the 2014 report, even the laws limiting what data can be collected and shared don’t always stop data brokers from getting the information they want.

For example, HIPAA may prevent brokers from accessing direct health records, but they could still deduce people’s health conditions from other data – medications they buy, health magazines they subscribe to, lifestyle products they purchase, etc.

“They may not have information from your doctor’s office,” George said. “But they can infer health information about consumers and then sell that.”

This type of roundabout data collection made headlines in 2012 after Target indirectly exposed a Minneapolis teen’s pregnancy to the girl’s father through targeted ads sent to their home.

Data brokers are not required to ask for consent before they collect and share data so consumers are unaware what pieces of their personal information are owned by whom. They may not even be aware their personal details were mined in the first place.

“It’s an enormous privacy invasion to compile information… about individuals, largely without their knowledge,” said Jay Stanley, a senior policy analyst at the American Civil Liberties Union who specializes in privacy issues. “[Data brokers] are basically doing to Americans what the Stasi did to the East Germans.”

Stanley believes that if the industry were more transparent and people could see the detailed information that’s been collected about them, “they’d be very unhappy.”

In her testimony before the Senate Commerce, Science and Transportation committee in 2013, Pam Dixon highlighted a number of then-active data broker lists that she believed “should not exist.” Among them was a database of people suffering from genetic diseases, a list of police officers’ home addresses and a list of rape victims selling for about eight cents per name.

Privacy aside, an unregulated data broker industry could also heighten cyberthreats to personal information, according to Dixon.

Compiling massive databases of valuable information in one place makes them “juicy targets” for hackers, she says, and because not all brokers employ extensive security procedures, enacting baseline security standards would be “a huge step forward.”

Identical bills targeting big data have been introduced in the Senate and House.

Dubbed the “Data Broker Accountability and Transparency Act,” the House and Senate versions aim to give Americans more autonomy over their information. They would require data brokers to let consumers access information being held about them, give them the right to correct inaccurate data, and allow them to opt out of data sharing all together.

Staffers from the office of Sen. Al Franken, D-Minn., who co-sponsored the Senate bill, called the measures an important first step toward making the data industry accountable for their treatment of personal information.

Though the proposed legislation Dixon doubts the bills’ ability to truly give people more autonomy over their data.

She doesn’t believe people would take the time to sit down and correct the vast amount of inaccurate information brokers have about them – there’s simply too much of it.

The World Privacy Forum estimates that nearly 50 percent of all data broker information is incorrect. When companies allow consumers edit false information, Dixon said, they’re essentially saying, “We want you to work for us for free.”

In its report, the FTC recommended that the government create a centralized database where people could go to see all the information data brokers have collected on them and opt out of sharing without having to go through individual brokers. However, the bills before Congress don’t include such a system.

“This dream of one piece of legislation that’s the silver bullet to fix the problem, that’s never going to happen,” Dixon said. She believes more nuanced laws directed at individual sectors of the data broker industry would prove more effective than such broad stroke actions.