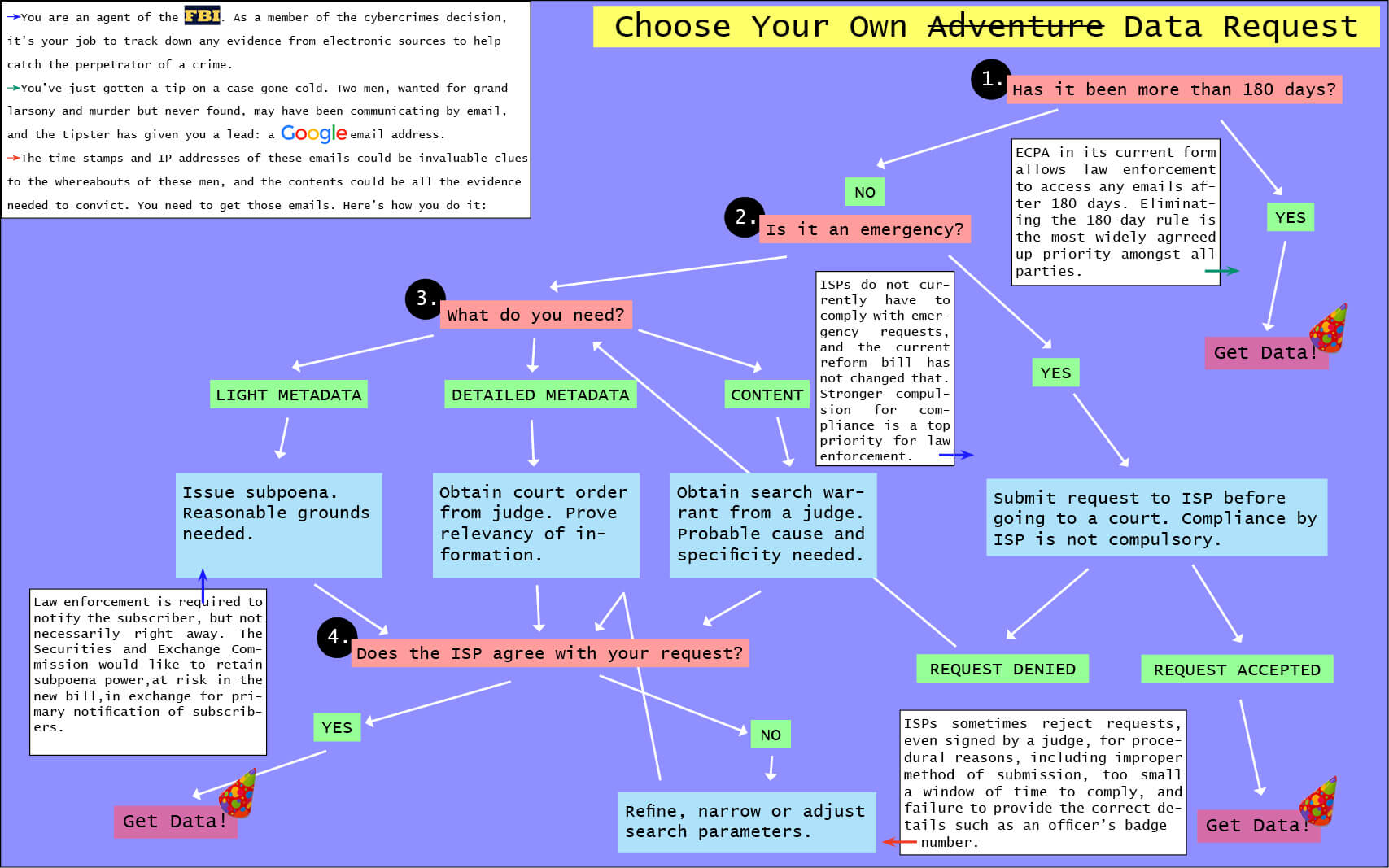

WASHINGTON — It’s 12:01 a.m. on day 181 after receiving an email from a friend. For the past six months, the government would have needed a search warrant to read the contents of this email. Now it’s fair game.

The Electronic Communications Privacy Act of 1986 allows the browsing. After 180 days of sitting in your cloud storage—far longer than any 1980s email user would have kept it because of storage limits—an email has significantly less privacy protection.

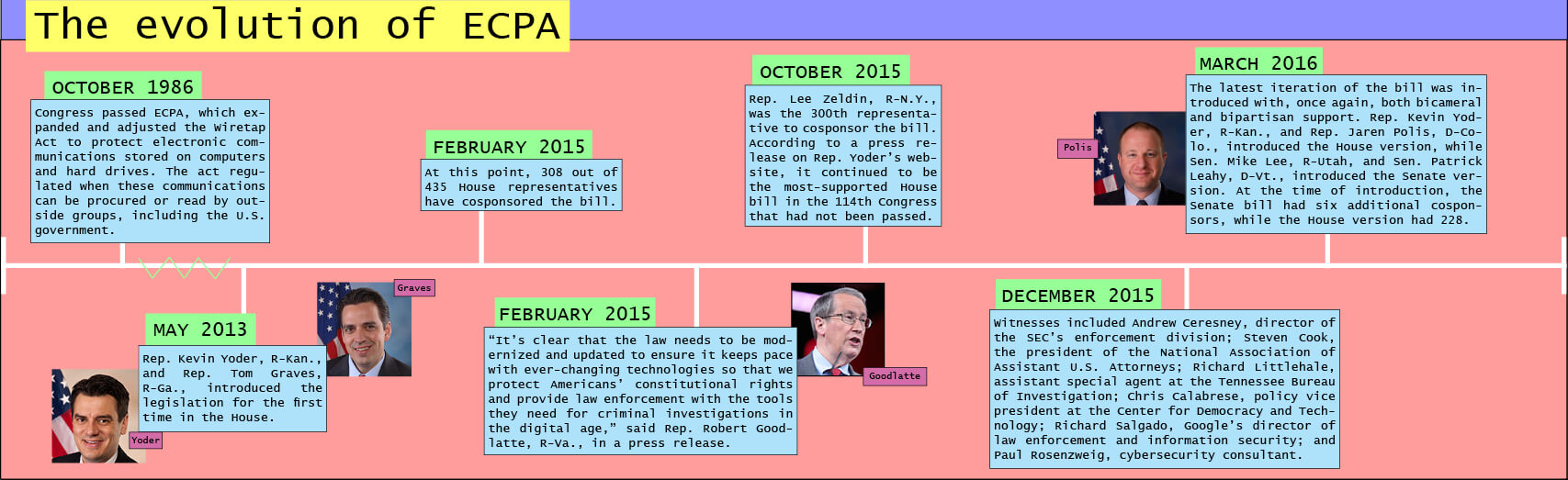

In passing the law 30 years ago, Congress was trying to keep up with rapid changes in communication. The legislation sought to protect the privacy rights of electronic data transmissions via computer, in the same way phone calls already were.

Some members of Congress want to catch the law up to today’s technology realities. Reps. Kevin Yoder, R-Kan., and Jared Polis, D-Colo., introduced the Email Privacy Act in January 2015, and it has 312 co-sponsors, with a nearly equal number of Democrats and Republicans. In its current form, the bill would require eliminate the 180 day rule entirely, and make it so any law enforcement official would always need a warrant to see the contents of an email.

But it has yet to get past the House Judiciary Committee, making it the most supported bill in the House that has not yet gone to a floor vote, according to a press release from Polis.

The committee’s chairman, Rep. Robert Goodlatte, R-Va., announced in February that his committee would hold a final review of the legislation. Goodlatte said in a press release on Feb. 3 that he looks forward to bringing the bill to a vote at an unknown point in the future.

A false start

The fact that ECPA has not changed over the past 30 years, however, is not for lack of trying. In 2013, Yoder introduced the Email Privacy Act in the 113th Congress, along with Rep. Tom Graves, R-Ga.

It was assigned to the House Judiciary Committee, and .Goodlatte said reforming ECPA would be one of the committee’s main policy priorities. By the end of the 113th Congress, the EPA had 272 cosponsors: 174 Republicans and 98 Democrats. But it did not come to a vote in the Judiciary Committee and died at the end of the 113th Congress in December 2014.

Goodlatte declined an interview for this story, but said in a statement that reforming ECPA has been a priority for him.

“I have been working with members of Congress, advocacy groups, and law enforcement for years on many complicated nuances involved in updating this law,” he said in the statement.

Keeping pace

ECPA didn’t always seem outdated. When it was written in 1986, five years before the World Wide Web and 10 years before companies like Hotmail offered free email accounts, it seemed reasonable. Internet access and online storage services were expensive, so people would download emails to their computers and then delete the online version shortly after opening them.

Fast forward 30 years, and Gmail users in 2016 can let thousands of unread emails live in their inboxes without paying a dime.

Because the law was created before the age of the iPhone, it’s also unclear what exactly ECPA encompasses, said Julian Sanchez, a senior fellow at the libertarian Cato Institute. The law protects “electronic communications,” which could include a broad category of data—photos texted to friends, Twitter direct messages or Facebook chats—apart from email.

“I think it’s an easy move to say even if it’s an IM or something, [it’s] obviously really the same thing,” Sanchez said.

One court case, zero laws

One of the strangest parts in the Email Privacy Act’s story, legal scholars say, lies in the fact that the courts have already ruled warrant exceptions to be unconstitutional.

In 2010, the 6th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals ruled in United States v. Warshak that the government should always be obligated to get a search warrant to read emails. Because there is a “reasonable expectation of privacy” for the content of emails stored in servers, the court held, the Fourth Amendment unequivocally applies to them.

Since then, the decision has effectively become the law of the land; very few agencies actually use the 180-day loophole to their advantage. Following Warshak, the Department of Justice voluntarily adopted a policy requiring warrants to read emails, regardless of date sent.

Despite the precedent, Warshak is still worth writing into law, says Albert Gidari, the director of privacy at the Stanford Center for Internet and Society.

“The point is that there is a statute on the books that was written at a time with technological assumptions that are no longer valid,” he said. “And that’s why Congress should clean up that law and eliminate any confusion about it.”

Very few people disagree that ECPA needs to move past the 1980s. Eighty-six percent of voters support changing ECPA when told about the law’s basics, according to a poll by a digital advocacy group. Without endorsing a particular bill, the White House said that ECPA is outdated and needs to be reformed in response to a related 2013 petition signed by over 100,000 people.

A coalition that includes civil liberties groups, technology groups such as Apple and Google, and the U.S. Chamber of Commerce sent a letter to the House Judiciary Committee in support of the EPA in January 2015.

“Successful passage of ECPA reform sends a powerful message—Congress can act swiftly on crucial, widely supported, bipartisan legislation,” the letter said. “Failure to enact reform sends an equally powerful message—that privacy protections are lacking in law enforcement access to user information and that constitutional values are imperiled in a digital world.”

The two sides of the privacy coin

However, federal and state agencies have dug in their heels. They don’t necessarily object to eliminating the EPA’s 180-day rule, but the search warrant requirement would shut them out from access. Only criminal law enforcement—not civil—can request search warrants.

Instead, civil law enforcement agencies like the Securities and Exchange Commission would have to subpoena individual customers, not Internet service providers like Google, to access emails.

Even though ECPA currently allows these agencies to subpoena ISPs, the SEC has not used that power in the wake of Warshak, Division of Enforcement Director Andrew Ceresney said at a House Judiciary Committee oversight hearing in December. Losing the ability to go through the company would “pose significant risks to the American public,” he said, because individuals are much less likely to cooperate with investigations than third parties.

“Unsurprisingly, individuals who violate the law are often reluctant to produce to the government evidence of their own misconduct,” Ceresney said, according to the hearing transcript.

A better ECPA reform bill would allow agencies to subpoena ISPs if the individual did not comply, he said in the hearing.

When reached for comment about specific cases in which not having being able to subpoena email providers hurt investigations, the SEC said that it would defer to Ceresney’s testimony, in which he said that his agency can’t know how much the post-Warshak policy has hurt the SEC.

Civil rights groups and voices in the tech community have pushed hard in the opposite direction.

Sanchez said ECPA’s current lack of a clear “electronic communications” definition may result in law enforcement applying the law unevenly.

“There are all sorts of services where you are storing data remotely, and the company has some type of access to it, or does something to it to provide you with some kind of additional or enhanced service,” he said. “There’s that whole range of different things they’re doing with the data that could give rise to a claim that you just don’t have the same kind of expectation of privacy.”

The Internet service providers themselves have a huge stake in this, since they want to ensure their users’ privacy is protected uniformly. The current confusing standards do not point toward a clear enforcement procedure, said Richard Salgado, Google’s director of law enforcement and information security, at the December hearing.

“By creating inconsistent privacy protection for users of cloud services and inefficient and confusing compliance hurdles for service providers, ECPA has created an unnecessary disincentive to move to a more efficient, more productive method of computing,” his prepared statement for the hearing said.

Gidari said that he understands that civil law enforcement agents have a difficult job; crimes are sophisticated, and emails can help prove of intent of fraud. However, he rejected the idea that civil law enforcement agencies need to access messages to do their jobs, since it’s “not the only evidence of a crime.”

“You shouldn’t be willing to trade off the huge intrusion into people’s lives that may be even tangential to an investigation for the purpose of making it a little easier for them to do their job,” he said. “They’re not there to do the job easily. They’re there to do the job.”

If the SEC were able to enact the type of ECPA reform that Ceresney suggested in testimony, the power to bypass the warrant requirement would also transfer geographically, encompassing hundreds of federal agencies and thousands of state ones, Gidari said.

“The New York Sanitation Department would have the power to subpoena your email,” he said.

Why now?

Despite past “stonewalling” of the Email Privacy Act, momentum seems to be building during this Congress, said Mark Jaycox. The champions in the House—Yoder, Polis and Graves—have done a good job pushing the bill, he said, but the conversations about encryption surrounding the Apple v. FBI case may have done even more to spur movement.

“I certainly think that when we’re talking about encryption, we’re also talking about the larger issue of security,” he said. “The growing awareness of security may have played a role in the cosponsors in [the EPA].”

While Goodlatte said his committee would act on the bill, the current session of Congress ends in December and the measure needs approval by both the House and Senate. If not, it’s back to the starting line for EPA in January.

“It’s all on Representative Goodlatte right now to hold a markup and to advance the bill,” Yoder said. “Because it’s six years too late on the issue already.”