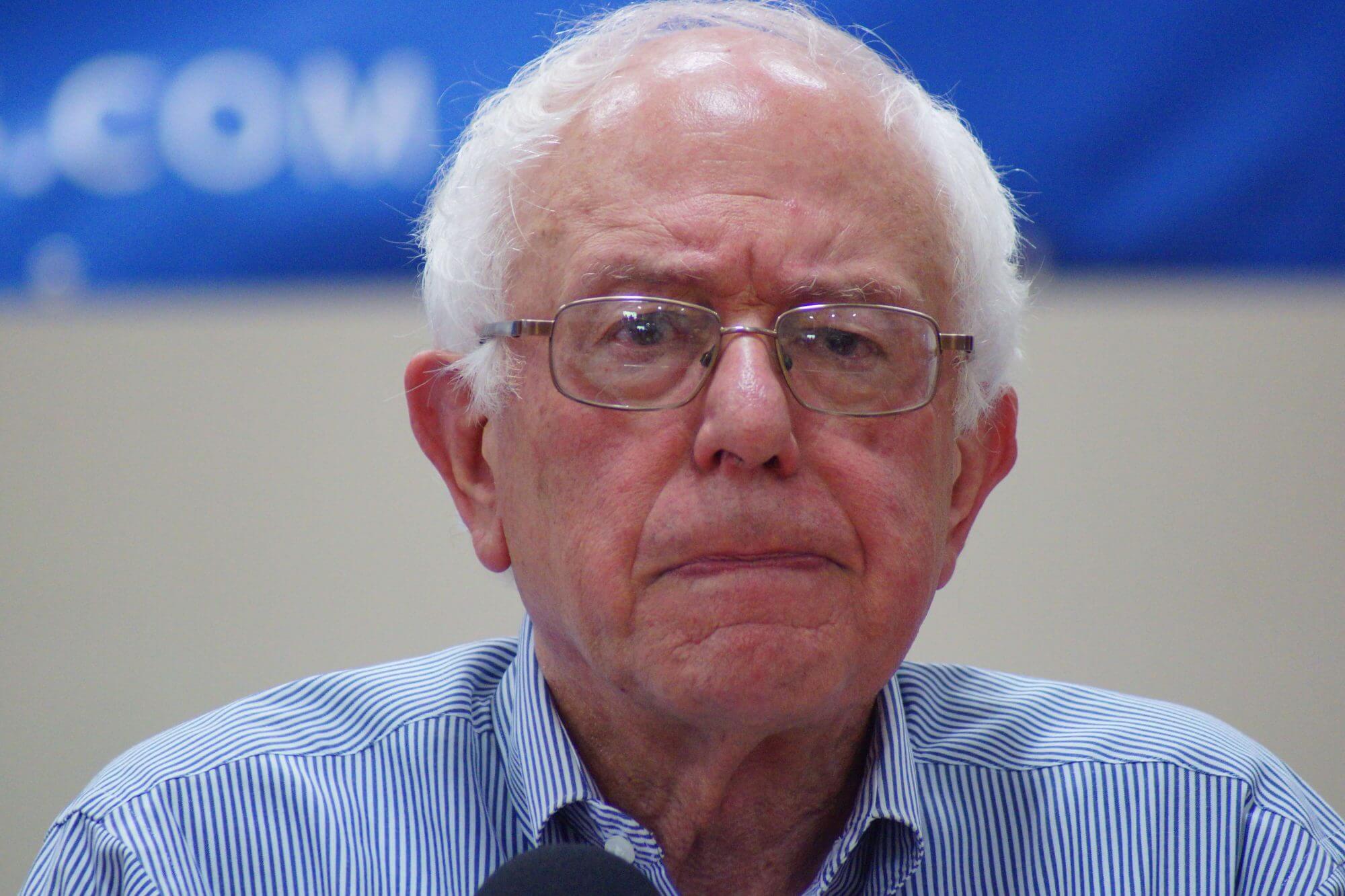

WASHINGTON — Bernie Sanders’ “political revolution” could be losing steam after a string of disappointing losses in Tuesday night’s primaries. As the gap in the delegate count widens between the Vermont senator and Hillary Clinton, experts say his chances of winning the Democratic nomination have slipped out of reach.

Clinton swept Sanders in all five of the March 15 primaries. While her victories in Illinois and Missouri came down to the wire – Missouri went her way by just over 1,500 votes – she breezed through Florida, North Carolina and Ohio with wins in the double-digits.

The former Secretary of State now leads the Democratic primary race 1,139 pledged delegates to Sanders’ 825.

Heading into Tuesday, Sanders’ prospects seemed to be looking up. His come-from-behind victory in Michigan on March 8 led many to believe that his liberal, populist, message was resonating well in the industrial Midwest, and he could give Clinton a run for her money.

Unfortunately, momentum from Michigan didn’t translate into positive results on Tuesday in states like Ohio and Illinois.

One major contributor to Sanders’ bad night was that — unlike in Michigan — his support among white voters didn’t outweigh Hillary Clinton’s strong base in minority communities.

According to CNN exit polls, 56 percent of Michigan’s white voters went for Sanders, compared to only 47 percent in Ohio and 44 percent in Florida. In Michigan, Sanders also fared slightly better among non-white voters, earning 34 percent support compared to 32 percent in Ohio and 24 percent in Florida.

“What happened in Michigan was more of an outlier when it comes to how Sanders performed with the white and African-American vote, compared to what’s going on overall,” said Nathan Gonzales, co-editor of the Rothenberg & Gonzales Political Report.

He believes that while Sanders has appealed to a vocal minority of left-wing Democrats, his supporters aren’t representative of the party as a whole, so securing the nomination would be difficult.

And the math on the delegate count doesn’t look good for Sanders either.

On Tuesday, Hillary Clinton expanded her lead over the senator to over 300 delegates, a gap that could prove insurmountable, even though primaries roll on into June.

Unlike many Republican primaries, which are winner-take-all, Democratic primaries and caucuses award delegates proportionally. Because of this, margins of victory in those contests are just as important as the wins themselves.

Winning by a hair in a big state may make for bold headlines, but in terms of the total delegate count, narrow victories don’t do much good.

In Michigan, Sanders overcame a double-digit deficit in the polls and claimed the state, but he only walked away with seven more delegates than Clinton. In fact, he lost ground in the overall race that night when he was crushed in Mississippi, with Clinton locking down 30 delegates to Sanders’ four.

What happened March 8 was symptomatic of Sanders’ problem in the race as a whole. While many of Clinton’s wins have been blowouts, Sanders’ victories have come by relatively small margins.

The nine states Sanders won have given him a net gain of 85 delegates over Clinton in those states, but in Clinton’s eighteen victories, her net gain has been 399 delegates.

Geoffrey Skelley, an analyst at the University of Virginia’s Center for Politics, said that Sanders may have a decent showing in the rest of the March primaries – Alaska, Arizona, Hawaii, Idaho and Washington. But given Sanders’ current standing in the delegate count, Skelley doesn’t think there’s much reason for optimism going forward.

“The problem for him now is that he can’t just do somewhat well or keep it close – 50/50 is far from cutting it for him,” Skelley said. “I don’t think there’s any path for him at this point.”

Sanders’ delegate deficit widens even more once super delegates are factored in. A super delegate is an unelected Democratic delegate – typically a party veteran, or elected official — who is free to vote for any candidate they want, regardless of who voters in their state choose.

Though super delegates won’t officially vote until the Democratic National Convention in July, 467 have already committed to Clinton compared to only 26 for Sanders.

According to Gonzales, the distribution of super delegates is lopsided because they are one of the few groups where “party loyalty still matters.” Sanders only began calling himself a Democrat when he launched his presidential bid, so it’s not surprising that many party loyalists are hesitant to support him.

Even if his chances of capturing the nomination are slim, Sanders’ campaign may yet have a lasting impact on the Democratic Party.

“There’s clearly a lot of energy on the left wing of the party, and as long as economic conditions remain roughly where they are, I expect that energy to continue,” said William Galston, a senior fellow at the Brookings Institution.

According to Galston, the challenge for party leaders going forward will be determining how best to take that energy and shape it into a political reality.

“When you make the transition from protest to politics and then from politics to policy, you have to start thinking differently,” he said in a telephone interview. “Things that sound good when they’re shouted out in a humongous political rally may not work that well as policy prescriptions.”