WASHINGTON— A half-century after passage of the landmark Civil Rights Act and in the wake of federal reforms in public education, test scores for black and white students’ scores do not look much different than those in the 1960s.

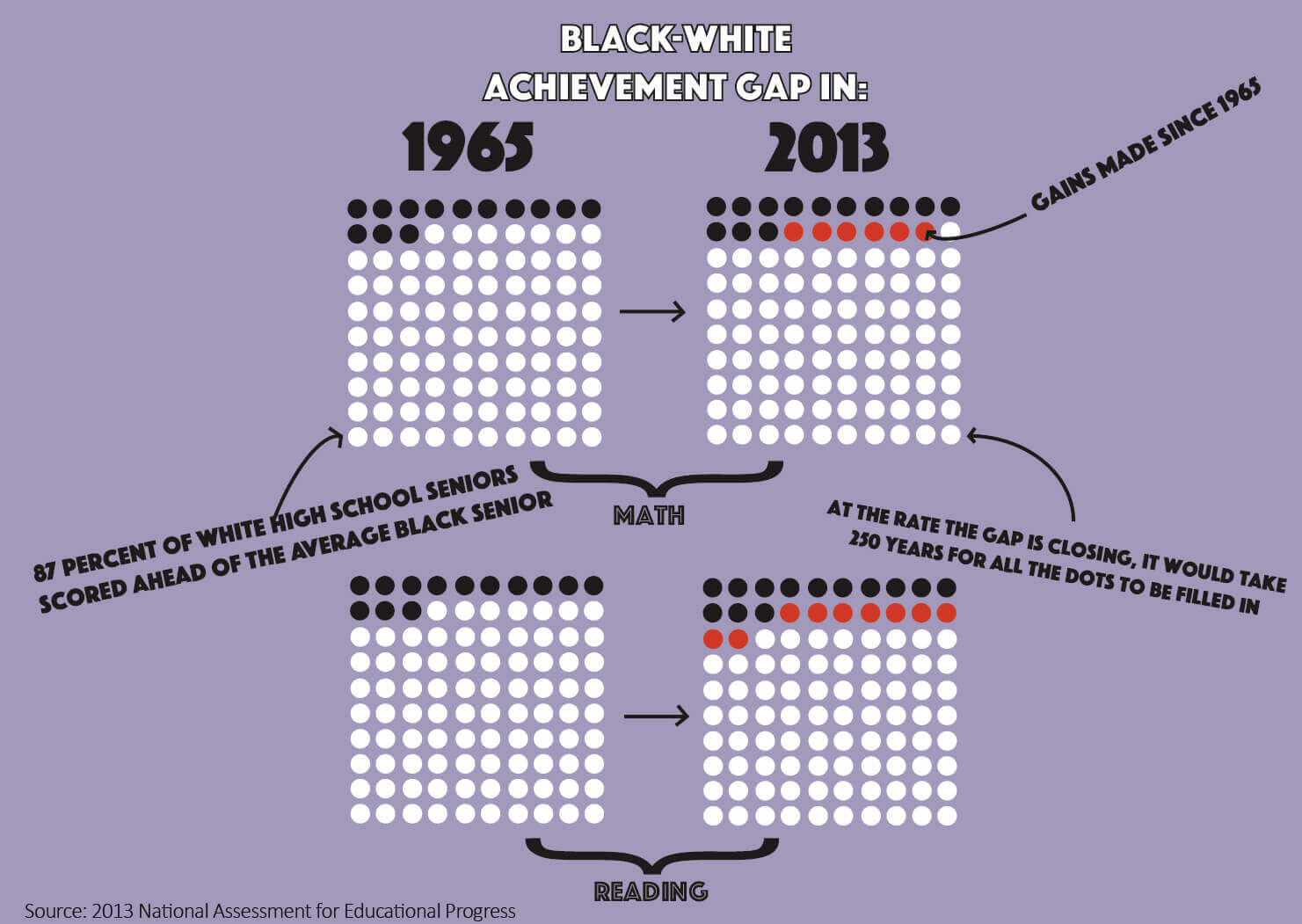

In 1966, a government-commissioned report found that 87 percent of white high school seniors scored better on math tests than their black peers’ average. Fifty years later, this difference has only decreased by six points, according to a report released by the Harvard University-based journal Education Next. A similar gap in reading scores has decreased by only a few more points.

At this rate, the reading achievement gap between black and white high school students will not close for 150 years, said Eric Hanushek, senior fellow at the Hoover Institution at Stanford University and a report contributor who analyzed test score data from the 2013 National Assessment for Educational Progress. Math scores would not balance out for 250 years.

“It doesn’t seem that we’re doing much better now than we did back then,” he said in a telephone interview.

Education reformers haven’t given up. Although the days of school desegregation laws have passed, advocates are pushing for other federal policy changes to level the playing field.

From de juré segregation to de facto racial imbalances

As a requirement of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, the U.S. Office of Education commissioned a report to examine how to equalize educational opportunities, the first national study attempting to understand student success. Sociologist James Coleman led the team of researchers that released the report in 1966 after surveying a whopping 150,000 students across the country,

One of their main discoveries: the composition of a student’s peer group was more important for learning than any other school-related factor. Black students performed better if they went to school with white students, whose own achievement wasn’t negatively affected in integrated classrooms.

In 1966, this pointed to a clear fix: desegregate schools. The Brown v. Board of Education case had already declared de juré segregation was illegal, but Congress took the decision and ran with it. The Civil Rights Act of 1964 continued cutting off federal aid to schools that did not comply with desegregation orders.

Controversial early-1970s busing programs helped integrate schools between districts by sending lower-income black students to majority-white schools in affluent areas.

But similar to the black-white achievement gap, racial balance in schools has improved only incrementally since the 1960s, despite decades of intervention, according to the Education Next report, a bicentennial review of education reforms since Coleman’s work. The average percentage of black students’ white schoolmates has inched up from 22 to 27 percent, after large gains made in 1980s dropped off.

Current demographics are difficult to compare to 1960s numbers because of an influx of Hispanic and Asian students into the public school system, said Dana Thompson Dorsey, an education policy professor at University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill. However, the “alarming number” of black students who attend schools with few or no white students mirrors the situation in the 1960s, she said in a phone interview.

She wrote a study released in 2013 outlining how a number of trends and policies—black-white residential segregation patterns, court decisions putting an end to school district racial desegregation, white students enrolling in private schools—have led to de facto resegregation, after years of improvement.

Considering the racial composition of schools is critical to understanding the achievement gap, she said. Some scholars, Eric Hanushek included, have pointed to research about “anti-intellectualism” among black youth claiming that black and Hispanic students with higher GPAs are less popular, and that doing well in school is “acting white.” By this thinking, a high concentration of black students in a school would exacerbate this trend of low performance.

But Thompson Dorsey said that race affects achievement in ways that are often outside of black students’ control. Students in majority-black schools are less likely to have opportunities for enrichment activities during the school year and the summer, she said. They are less likely to have access or be referred to honors and Advanced Placement classes.

Black and Latino students are also more likely to experience student discipline, suspensions and expulsions than their white and Asian counterparts, she said.

“If you are having these disparities that are going on throughout a school year, and it’s happening predominantly to students of color, to black and Latino students, they’re not learning,” she said.

The new policy fix: teacher equity

Today, after the dismantling of racial desegregation programs like busing, improving teacher effectiveness and quality needs to be the next policy push, Hanushek said.

Black students are over four times as likely as white students to attend schools where at least 20 percent of its teaching staff lacks proper teaching credentials, according to data analysis from the Education Department’s Office of Civil Rights.

This lack of experience and credentials matters a lot, said Kati Haycock, president of the Washington-based nonprofit The Education Trust.

Disadvantaged students are more likely to enter school “a little behind” more privileged ones because of poverty, she said, and would benefit most from having well-educated teachers who can catch them up in reading and vocabulary skills.

“We’re far more likely to assign kids who are entering school behind to our least experienced, least well-educated and least effective teachers,” Haycock said in a phone interview. “Not surprisingly, the effect of that is that instead of eliminating the gap, the gaps actually grow.”

Federal education law specifically says that low-income students should not receive subpar services – and that includes teacher quality. However, the language of the law is vague and difficult to enforce, Haycock said. It would require a more data collection and reporting.

Federal policy changes may be on their way. Newly confirmed Education Secretary John King has said that he wants to “elevate the teaching profession.” The department has also requested $1 billion for its FY17 budget to create salary incentives for teaching in high-poverty schools and to fund teacher development programs, according to a department press release.

“We need to prepare, attract, and keep school leaders of diverse backgrounds who can create school cultures that bring out the best of students and staff in a climate that supports growth and learning for all,” King said in a statement at a House Education and the Workforce Committee oversight hearing in February.

But racial imbalances have psychological consequences for black students — transcending what teachers can do, Thompson Dorsey said.

Black students in Southern rural communities, recently interviewed by Thompson Dorsey, told her they feel white families do not want them to go to school with their kids, she said. And only interacting with peers who look like them makes them less likely to venture outside their community, she said, because they are not used to environments where they are one of few black people.

“Basically, we could have students in these schools be the scientist that cures cancer or Alzheimer’s, or some other remarkable feat (that) is awaiting some of these young students. But they don’t feel prepared socially, emotionally or academically to leave their community,” she said. “And I think a lot of that has to do with the fact that they’re segregated.”