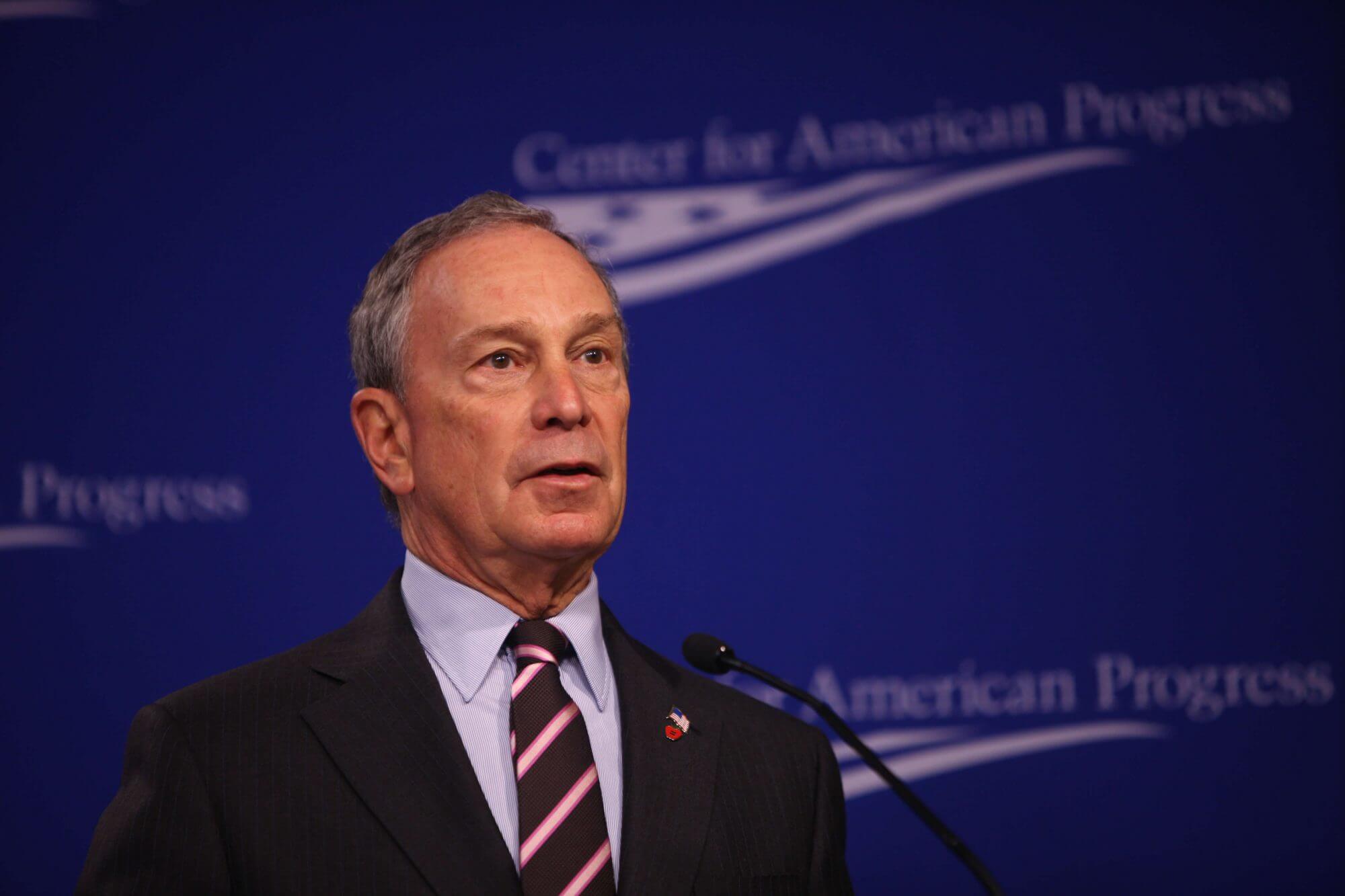

WASHINGTON — Despite the many surprises of the 2016 presidential campaigns, most agreed there was one sure thing: If Michael Bloomberg ran for president, he would not win. However, a Bloomberg administration almost certainly would have had improving public health as a centerpiece, health policy expert say.

Bloomberg announced last week that he would not run for president as an independent in 2016 for fear of splitting votes with the Democratic nominee and ensuring a Donald Trump presidency. Though he never released a plan for health care, his policies and public statements during his decade as mayor of New York City provide an interesting blueprint.

A billionaire philanthropist, Bloomberg has long dabbled in presidential politics, with many convinced he would stage a campaign back in 2008. At the age of 74, it is unlikely that Bloomberg will run for president again.

During his tenure as mayor, Bloomberg was a vocal public health advocate. From leading the push in 2002 for New York City to issue the first major smoking ban in bars and restaurants nationwide to his use of new health information technologies, Bloomberg invested in health.

“There was a big investment in collecting health data and in using the power of government and regulation when it was necessary to protect public health,” said Michael Gusmano, a health policy expert at the Hastings Center outside New York City, a research organization that studies bioethics.

Calling his policies more within the Democratic vein, Gusmano said Bloomberg has had a stronger focus on public health than any other big-city mayor.

The November election will decide whether the legacy of President Barack Obama’s health care law is solidified or torn apart.

In the past, Bloomberg has said both critical and supportive things about the Affordable Care Act. During the botched launch of the Affordable Care Act’s website, Bloomberg shot down Republican criticisms, saying that law— although not perfect — was needed to fix the cost of medical care in the country. But Gusmano predicted that as president Bloomberg would have stood behind the goals of universal coverage.

Bloomberg has raised the alarm over the costs of Medicaid expansion and of subsidies for Obamacare’s individual mandate requiring everyone to have insurance, Gusmano said. In addressing the rising cost of health care and keeping insurance affordable, a Bloomberg administration would have been more fiscally conservative while looking to preserve access, he said.

However, two major candidates for the presidency are suggesting just that. Democratic candidate Sen. Bernie Sanders has proposed moving to a single-payer health care system similar to Medicare, where everyone would be insured by the federal government. Republican frontrunner Donald Trump has carried the Republican line of “repeal and replace,” essentially aiming to gut Obamacare and replace it with a Republican-developed alternative.

Expert objections to Sanders plan usually reside in the fact that it is politically impossible to achieve. Anything resembling a single-payer, universal coverage plan has already failed to pass even while Democrats controlled Congress and the White House, said Dr. Shana Charles, an associate at the University of California-Los Angeles Center for Health Policy Research.

“It’s already failed in the most favorable of circumstances, and Sanders would not be facing those,” Charles said.

Trump’s plan to scrap or largely change the health care law is almost impossible, said Henry Aaron, a health policy expert at the Brookings Institution.

“Democracies, apart from times of cataclysm, economic catastrophe or war, never ever scrap institutions wholly and replace them with something really quite radically different in character,” Aaron said.

Given the challenges that both Sanders and Trump face in large-scale change of Obamacare, the pragmatism of Bloomberg’s success as a public health policymaker in New York City might serve to guide whoever takes the Oval Office in November.

The changes candidates could likely make to the health care law would depend on their choice for secretary of health and human services, Charles said. The secretary, through rules, regulations and programs, could make a huge difference in how the law ends up being implemented and funded, she said.

In short, Bloomberg was a manager, Aaron said. And managing the law, instead of trying to replace it, might be the best option.

Faced with the likelihood that Obamacare will remain the law of the land, and with a Gallup poll last month showing roughly eight in ten Republican and Democratic voters rated health care as an extremely important issue, the presidential candidates might be wise to channel a little Michael Bloomberg.