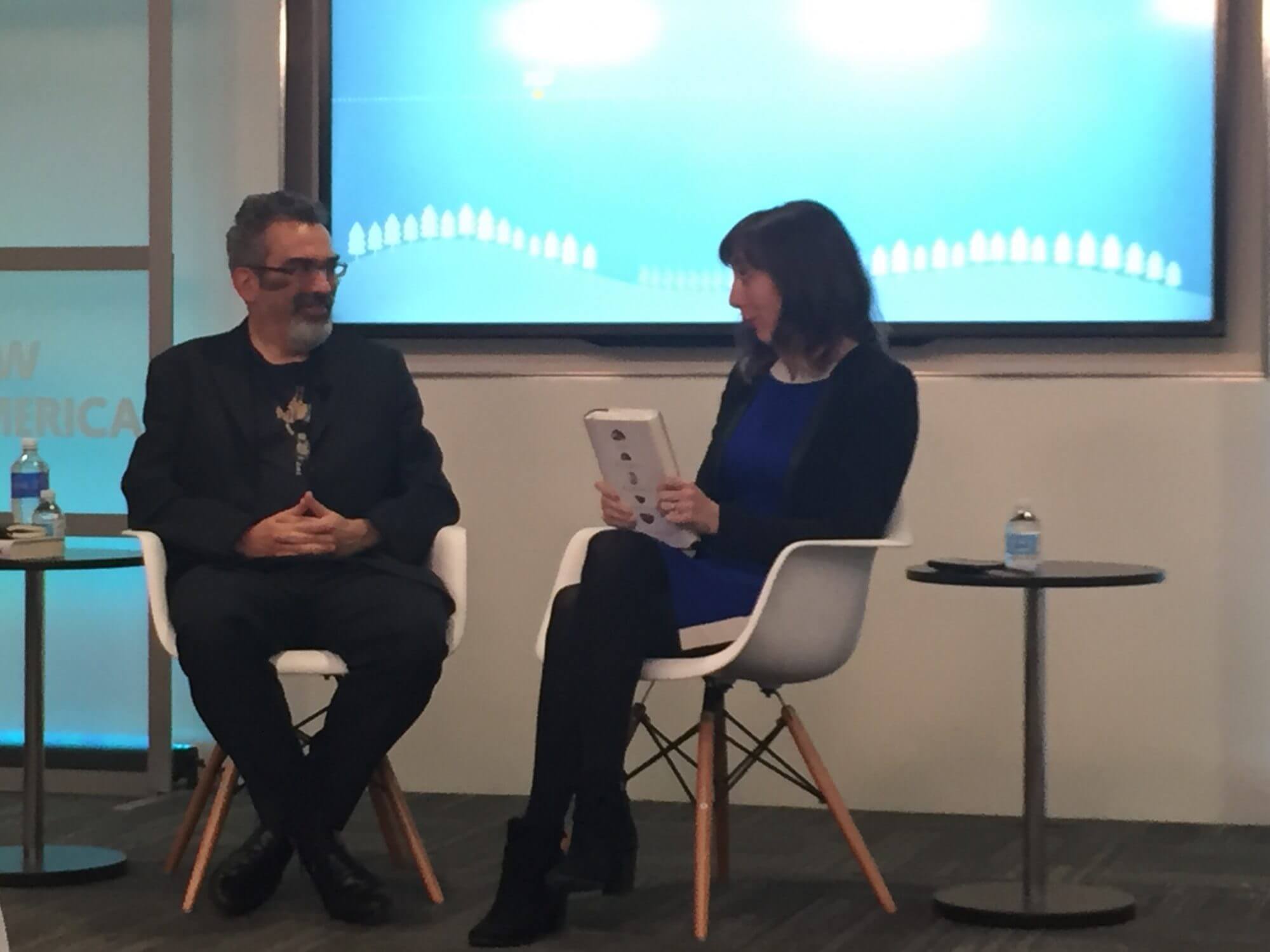

Author Oliver Morton discusses his new book that investigates geoengineering as a response to climate change. (Allyson Chiu/Medill News Service)

WASHINGTON—Innovative scientific techniques that alter Earth’s natural systems to mitigate climate change pose potential risks to the planet that should be evaluated before being put to use, environmental experts said Monday.

Geoengineering—also known as climate intervention—is one possible response to climate change, said Oliver Morton, author of “The Planet Remade: How Geoengineering Could Change the World”.

Stepping up exploration in the field is a part of the effort to comply with emissions standards set by the Paris climate talks in December. To keep global temperatures from rising over 2 degrees from pre-industrial levels, reducing carbon emissions alone is not enough, said Morton.

“It’s unlikely to achieve the emission goals if you just rely on emission reductions,” he said at New America, a public policy institute in Washington. “The only way to do it is if you have a geoengineering technology to pull out carbon dioxide that gets into the atmosphere, or you get a time machine, so you can go back in time and stop the emissions beforehand.”

Despite the need for more efficient climate action, geoengineering is still a new area of study and no working models have been introduced into practice yet, said Edward Dunlea, program officer with the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering and Medicine. The academies released a study last year detailing the benefits and potential risks of geoengineering.

In Morton’s book, two approaches to climate intervention are carbon removal and sunlight engineering. Examples include cultivating photosynthetic plankton—to process more carbon dioxide and create oxygen—or releasing volcanic sulfur into the stratosphere, which creates a reflective veil that bounces sunlight back into space and cools the Earth.

However, the technology is not expected to act alone in reducing the effects of climate change, said Morton, a British science writer and editor at The Economist.

“Geoengineering is going to be an adjunct to other forms of climate action, not a replacement for them,” he said.

In addition to evaluating geoengineering techniques, the National Academies’ of Sciences, Engineering and Medicine study also analyzes how practical implementing the technology could be in the near future.

“All these techniques are proposed,” said Dunlea in a phone interview. “Very few have had a lot of on-the-ground research done — and none are actually in deployment.”

The academies’ study cautions against immediate use of any large-scale geoengineering technologies because risks include changing precipitation patterns and ozone loss, which can harm humans living in affected regions. However, it does state that research in the field should be continued in order to understand the risks and safely use the technology in the future.

“If it could be made to work in a way that was cost effective and could be deployed at a large enough scale, those approaches would have the ability to help effectively roll back the changes to the environment, so that’s really going after the root of the problem,” said Dunlea.

Despite the potential benefits, the idea of scientists manipulating Earth’s natural processes makes people nervous, said Dunlea.

“We know lots of things, but we don’t know everything, and there’s always the potential for things to go wrong, or go in a different way than we anticipate,” he said.