WASHINGTON — Jonathan Moreno, a leading bioethicist at the University of Pennsylvania, said Monday that a number of new neurotechnologies could have national security applications for use in warfare — but most will likely never be developed.

Moreno, who describes himself as an ethnographer studying military culture, said innovations in brain research — especially mind control — get picked up by all parts of culture, including the military.

“Commanders have always been concerned about the mind of their combatants and the people back home…We want them to be supersoldiers,” he said. “Brains make more of a difference in modern warfare than brawn.”

Moreno, author of a book called “Mind Wars: Brain Science and the Military in the 21st Century,” spoke at a bioethics seminar hosted by the National Institutes of Health.

He said some government funding for brain research is going to military research groups like the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA). The goal is to capitalize on emerging neuroscience research by developing technology applications for the battlefield.

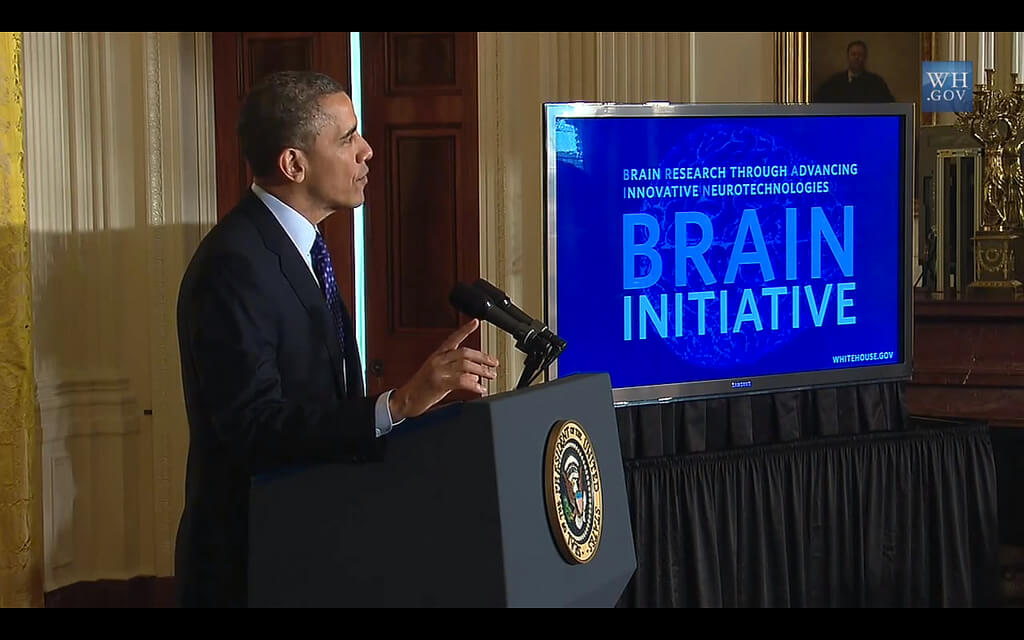

Funding for neuroscience research in the United States has increased in recent years spurred in 2013 by President Barack Obama’s Brain Research through Advancing Innovative Neurotechnologies (BRAIN) Initiative. The initiative – supported by several federal agencies, including DARPA — attracted federal funding.

On Capitol Hill, the 2016 fiscal year budget bill that passed late last year included $146.9 million in National Science Foundation funding for brain research, an increase of $40.5 million from the previous year. The figure comes from the office of Rep. Chaka Fattah, D-Penn., who has pushed for greater funding for brain research.

Though some research is geared toward reducing common warzone ailments like post-traumatic stress disorder,, other research seeks pharmacological tools to enhance soldier cognition.

One such drug, modafinil, marketed as Provigil, was developed to help treat narcolepsy disorder. However, according to Moreno, it has been approved for use by U.S. Air Force pilots since 2004.

There are many possibilities for emerging technologies, from functional MRI programs that can scan brain activity and replicate what the brain sees, to simulated brain networks used in programming autonomous weapons, Moreno said. It can sometimes seem like science fiction, he said.

In the decade or so since his book “Mind Wars” was published, Moreno said he has become more certain that few of these technologies will actually be used on the battlefield. That’s mostly due to the cost of developing and deploying the new tech.

He also cited what he sees as a lack of enthusiasm from U.S. war colleges for the somewhat fantastical sounding projects described in grant proposals. That’s an impediment to further research and development, he said.