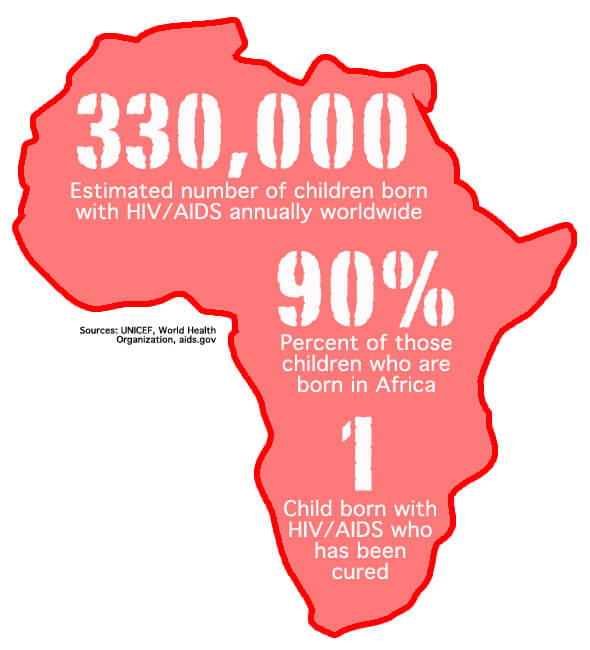

WASHINGTON–The announcement this month that researchers had effectively cured a toddler born with HIV was considered a breakthrough in the battle against AIDS. But for most of the approximately 330,000 babies born with the virus every year, experts say the discovery may not ultimately mean much.

WASHINGTON–The announcement this month that researchers had effectively cured a toddler born with HIV was considered a breakthrough in the battle against AIDS. But for most of the approximately 330,000 babies born with the virus every year, experts say the discovery may not ultimately mean much.

“It’s not a huge breakthrough,” said Rana Chakraborty, an expert on HIV and pediatric infectious diseases at the Emory University School of Medicine. “We are delighted obviously for the child and what it means for the mother. But when you have just one patient (cured) and the mechanism has not been put forward in terms of how the infection was stopped, none of this can be extrapolated out to the large group of other HIV-positive individuals.”

The first problem lies in the fact that there are not yet indicators that the method used to cure the Mississippi toddler, whose identity is being withheld by the researchers, will have the same results in other patients.

Second, the vast majority of children born with HIV are in impoverished areas, often in Africa, where access to any sort of care is often minimal. So even if the cure could be consistently duplicated, it would likely not be of any aid to most victims.

Chakbraborty said HIV-positive mothers still must relay on known treatments during pregnancy to reduce the risk of transmitting the virus to their child.

“If you know that you’re pregnant, you should get screened for HIV infection,” he said. “(If a woman tests positive), she can take the medications for her own health and to protect her unborn baby. There are options including a Caesarean section, and the baby should receive medication in order to prevent mother-to-child transmission.”

However, in areas of sub-Saharan Africa, where access to care is limited and poverty is widespread, even these preventive measures can be too expensive for most women. Of the more than 330,000 children born each year with HIV, more than 90 percent are in sub-Saharan Africa, according to data from the World Health Organization.

Sarah Crowe, a spokeswoman for UNICEF Executive Director Anthony Lake, said the yearly costs of treating women with HIV/AIDS in sub-Saharan Africa can vary between $381 and $1,034 through UNICEF programs. With nearly half of the population in that region of Africa living off of less than $1.25 per day according to WorldBank data, even with assistance from external organizations these costs can be prohibitive.

“(Eighty-seven percent) of the estimated 2.3 million children living with HIV/AIDS grow up in sub-Saharan Africa, and the vast majority are beyond the reach of these health services,” according to a Doctors Without Borders AIDS fact sheet. “They are condemned to die due to lack of access to treatment.”

Still, Crowe said, the news that a child in the United States born with HIV has been cured is a good sign for those with the virus around the world.

“The important thing is to continue this work,” she said. “We cannot drop the ball now when we’ve come so far, we need to continue the momentum when we are seeing results.”

The breakthrough came through an intense, but not atypical, form of treatment, according to news reports. The mother of the child, who is also remaining anonymous, did not realize she was HIV-positive until shortly before childbirth and did not undergo prenatal care that would have lowered the risk of passing on the virus.

“The care itself was not unique, it is the standard of care that is generally provided,” Chakbraborty said. “In this case the mother did not, however, receive prenatal care, and there are certainly questions around that.”

Once the child was born, doctors began treatment for HIV almost immediately. Two and a half years later the researchers, led by Deborah Persaud of Johns Hopkins University, announced March 4 that the child was effectively cured and showed no signs of the virus.

This rapid treatment of the child is in line with previous studies showing that children born with HIV have longer life expectancies if they begin treatment, which includes a combination of multiple medications, quickly after birth. Some reports indicate this child began treatment within 30 hours of birth.

“It demonstrates what we already know: It’s vital to test newborn babies as soon as possible,” Crowe said.

Despite public praise for the breakthrough, Chakbraborty stressed the announcement is not necessarily cause for optimism for most HIV/AIDS patients.

“I’m not sure it can provide hope because I would remind people that AIDS in the absence of therapy kills people,” Chakbraborty said.

Crowe also cautioned that more information is needed to determine whether the treatment that cured the child is likely to cure others.

“We really need to do further studies and have scientific verification of this case and view the results,” Crowe said.

With the vast majority of cases of mother-to-child HIV transmission coming from sub-Saharan Africa, this research may not translate into aid on the ground. Without treatment, children of HIV-positive mothers become infected with the virus between 30 and 50 percent of the, according to the WHO.

But there have been gains in recent years in reducing mother-to-child transmission. According to WHO data, African nations Botswana, Lesotho, Namibia, South Africa and Swaziland have all documented that more than 80 percent of HIV-positive pregnant women have received prenatal care including medicine to reduce the risk of transmission.

If the factor that effectively cured the child in the United States can be identified, some hope that it eventually could be distributed on a wide scale to those in need in Africa.

“It’s potentially good news to really understand what the impact means,” Crowe said. “Any form of research that will help to continue to reduce the rates of HIV is of course good news.”