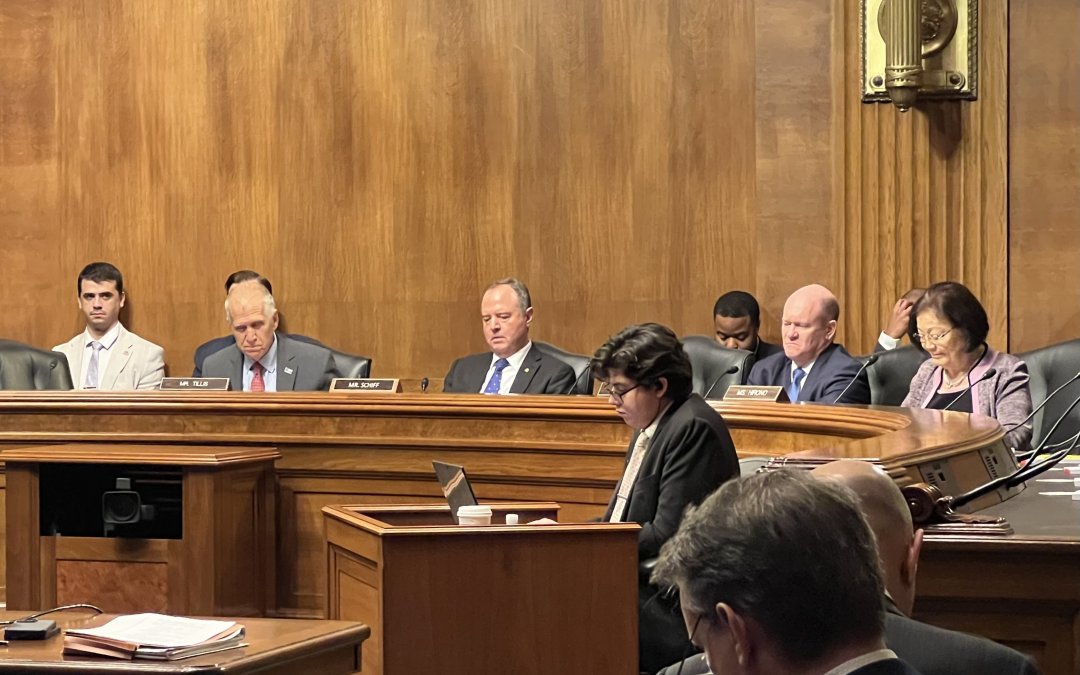

WASHINGTON — One day after questioning Attorney General Pam Bondi during a highly televised Senate Judiciary Committee hearing, Sen. Mazie Hirono (D-Hawaii) attended a much quieter discussion before a smaller audience on Wednesday.

“This is like a normal hearing,” Hirono said at the Intellectual Property subcommittee hearing. “It’s nice.”

The debate focused on the Patent Eligibility Restoration Act (PERA), which would expand patent eligibility in sectors including software and biotechnology. It aims to combat Supreme Court decisions from the 2010s that limited patent applications on diagnostics, software and business methods.

PERA advocates argue that such patent restrictions discourage innovation and investment in these emerging industries.

Subcommittee chair Thom Tillis (R-N.C.) has held hearings on the subject since 2019. He introduced the bill in 2023 with Sen. Chris Coons (D-Del.) as a co-sponsor.

Tillis announced in June that he would not seek re-election in 2026 and acknowledged during the hearing he had limited time to push PERA forward.

“Under my watch, which, incidentally, is over the next 452 days, it will be one of my top priorities in my office,” he said.

Former U.S. Patent and Trademark Office director Andrei Iancu said uncertainty in the patent system is “deadly,” referring to courts striking down patent applications on diagnostics. He said these denials limit disease detection options for consumers.

And Steven Caltrider, Chief IP counsel at the Dana-Farber Cancer Institute, said patent restrictions discourage private sector investment that helps the diagnostics come to fruition.

American University assistant law professor Charles Duan said in an interview with Medill News Service most PERA advocates come from larger pharmaceutical and tech firms.

“A lot of patent law comes down to who you think are the most important people in terms of who develops innovations,” Duan said.

Testifying on behalf of genetic testing companies, Pillsbury, Winthrop, Shaw & Pittman LLP partner Richard Blaylock said patents allow firms to privatize medical discoveries.

“PERA would slam the door shut on access to new biomarkers,” he said.

Making biomarkers patent-eligible would also harm patients, Blaylock said. Diagnostics test for a variety of biomarkers, but requiring permission from patent holders to perform those tests will put up roadblocks to critical care.

Duan said expanded patent eligibility leads to monopolies and reduced competition. Consumers experience that impact through higher prices and limited options.

That point was also raised by Mike Lemon, who testified on behalf of the National Retail Federation.

“Every dollar businesses spend fighting frivolous lawsuits is a dollar they cannot put toward lowering prices, hiring staff or improving service,” Lemon said.

For Mark Cohen, a senior technology fellow at the Asia Society of Northern California, international competition looms behind domestic impacts.

Cohen said China’s broadened patent laws give it a competitive advantage over the U.S. That could turn into a national security concern, he said, when technology is used for military purposes.

But Lemon said PERA would make it easier for foreign companies to apply for U.S. patents, allowing China to maintain its lead in the innovation race.

Still, combatting Chinese markets is a priority for Tillis.

“They represent a threat to Western democracy and open capitalist markets,” Tillis told Medill News Service. “To be honest with you, this is about always pacing ahead of China in my mind.”

Witnesses agreed on advancing American innovation. Even disagreements on how to best do so did not escalate.

“One of the beautiful things about patent law, Sen. Coons, is that it’s nonpartisan or bipartisan,” Iancu said.