WASHINGTON — President Donald Trump just announced a plan for TrumpRx, a new, government-run, direct-to-consumer online pharmacy.

It comes a day after Trump’s deadline for pharmaceutical companies to lower costs on prescription drugs. On July 31, Trump wrote a letter to the 17 largest pharmaceutical companies demanding that they align their drug prices to those of other high-income countries, a policy known as most-favored-nation pricing, by Sept. 29.

Pfizer is the first to announce a deal with the Trump administration, agreeing to voluntarily sell its medications to Medicaid at discounted prices in line with other developed nations as well as sell their drugs at a discount direct to consumers on the new TrumpRX site.

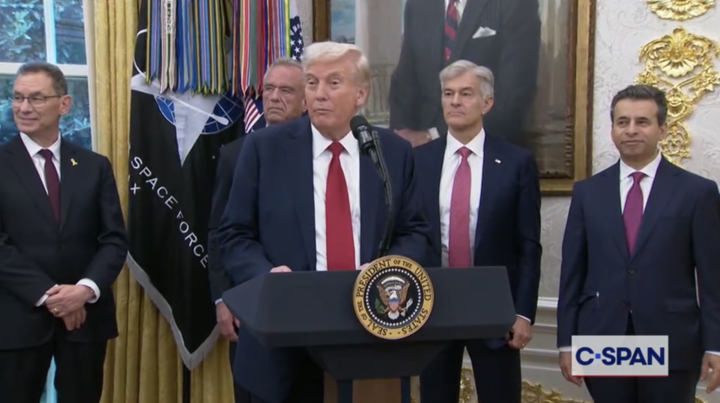

“I think today we’re turning the tide, and we are reversing an unfair situation,” said Pfizer CEO Albert Bourla in a press conference with Trump on Tuesday.

Other pharmaceutical companies have taken initial steps to close the pricing gap between U.S. and foreign markets, with AbbVie and Bristol Myers Squibb recently pledging to launch their respective drugs in the U.K. to match the higher list price in the U.S.

The Pfizer deal is unlikely to have a large impact on reducing drug costs for the vast majority of Americans who have private health insurance, said Vincent Andolina, a retired pharmaceuticals regulatory expert. That’s because the cost reductions offered on TrumpRx are only accessible to patients who forgo using insurance, and consumers would likely pay less through insurance, despite how large TrumpRx discounts are.

For the more than 70 million people on Medicaid, they already receive the lowest price offered in the drug marketplace by law, so patients often pay minimal amounts out-of-pocket to start.

Americans pay nearly three times more for brand-name drugs than other developed countries, according to a 2024 report from the RAND Corporation, a nonpartisan research organization.

Pharma companies have argued that lowering prices would mean less money for research and new drug discoveries, but Lindsay Allen, a health economist at Northwestern’s Institute for Public Health and Medicine, disagrees.

“We know that drugs can be priced at what they are priced in other countries, and it will not harm the type of innovation that we’d like to see,” Allen said.

The discrepancy between prices in the U.S. and other developed countries is due to a number of factors, including the lack of pricing transparency and differences in health systems.

Most European countries use single-payer health care, meaning the government negotiates with manufacturers to determine drug prices. This gives the government leverage to determine the maximum price of a drug or even prevent a drug from getting to market if the pharmaceutical company doesn’t agree to a certain price.

In the U.S., most drug prices are negotiated by pharmacy benefit managers (PBMs) who serve as middlemen between pharmacies, insurers, and drug manufacturers. These PBMs don’t have to disclose certain costs, such as how much a drug costs a manufacturer to make and how much it gets sold to the pharmacy for.

PBMs also have an incentive for promoting certain branded drugs: rebates. Drug companies offer rebates to PBMs to get their drug a preferred status on the formulary, or the list of medications that can be prescribed. This favored status allows manufacturers to sell more of their drug, but the rebates do not lower the out-of-pocket costs that the customer pays. The PBM can retain the savings from those rebates.

Pharmaceutical companies, including Eli Lilly, Pfizer and AstraZeneca, have recently launched their own direct-to-consumer platforms, but Andolina said he’s skeptical of their efficiency.

“Direct-to-consumer, to me, doesn’t make sense, and regulation of pharmacy benefit managers makes more sense,” Andolina said.

Timothy McBride, a professor at Washington University in St. Louis’s School of Public Health, argues that a better approach to saving all consumers money on drug costs is for the government to focus more on using Medicare to negotiate prices. Which in turn can cut costs for everyone.

“The government is one of the biggest purchasers of drugs in the country,” McBride said. “We just haven’t used that power, basically, to go in and say, ‘Look, we’re buying millions of dollars of drugs, and we think the price is too high.’”