WASHINGTON — The Federal Emergency Management Agency’s flood insurance program is at risk of financial insolvency due to outdated flood risk mapping and an unsustainable business model, putting communities around the country that experience flooding at risk of damages and reduced home values, federal investigators say.

The National Flood Insurance Program, a federal program managed by FEMA that provides participating communities with federally funded flood insurance, is over $20.5 billion in debt, according to the Congressional Research Service — a financial status that has landed the program on the Government Accountability Office’s High Risk List.

Congress established NFIP because private insurance companies generally don’t cover floods, which are costly, said Chris Currie, director of homeland security and justice at the GAO. Currently, FEMA requires members of communities at high risk of flooding to pay premiums, but the rates have never accurately reflected flood risks since it began in 1968, and the program has not been able to cover the costs of the claims it has to insure, Currie said.

In October, FEMA implemented a new flood insurance rate system that increased premiums for new policy holders in an effort to better reflect hazards. While this is intended to increase revenues for the program, the higher rates are unaffordable to lower-income people, who become more likely to drop their policies, said Alicia Cackley, director of financial markets and community investment at the GAO. Cackley said the GAO recommends Congress appropriate more money for those who cannot afford the higher premiums.

Homeowners in areas that experience frequent flooding, especially those who live in an area with outdated or inaccurate flood maps, risk seeing their property value decrease and flood insurance rates increase, which can drive people out of their homes and leave the federal government to cover the costs, Cackley said. While FEMA is taking steps to address the financial problems, she said there’s still much at risk.

“It is a program in trouble,” she said. “Unless something changes, it’s not sustainable. It’s just going to continue to be a drain on the budget.”

Flooding is the most common and costly disaster in the United States. The average cost per flood event is around $4.6 billion and because of climate change, more severe weather events are increasing the frequency and intensity of flooding, according to Adam Smith, a lead scientist for the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration’s National Center for Environmental Information. The U.S. experienced more billion-dollar flood events in the last decade than it did during the three previous decades combined, Smith said.

“Both inland and coastal flooding events can be quite costly at destroying homes, businesses, and many forms of infrastructure while also disrupting commerce across many industries,” Smith said.

Throughout the last five years, the GAO has released several reports detailing the problems with NFIP. In an October study, the agency reported that FEMA’s flood maps — which identify areas at high risk of flooding and inform which communities FEMA will require or recommend buy flood insurance — are outdated and do not reflect current increased flood hazards like heavy rainfall from climate-related weather events.

There is no consistent or definitive timetable for when FEMA will update a community’s flood maps, according to CRS, leaving some communities across the country with maps that have not been revised for decades.

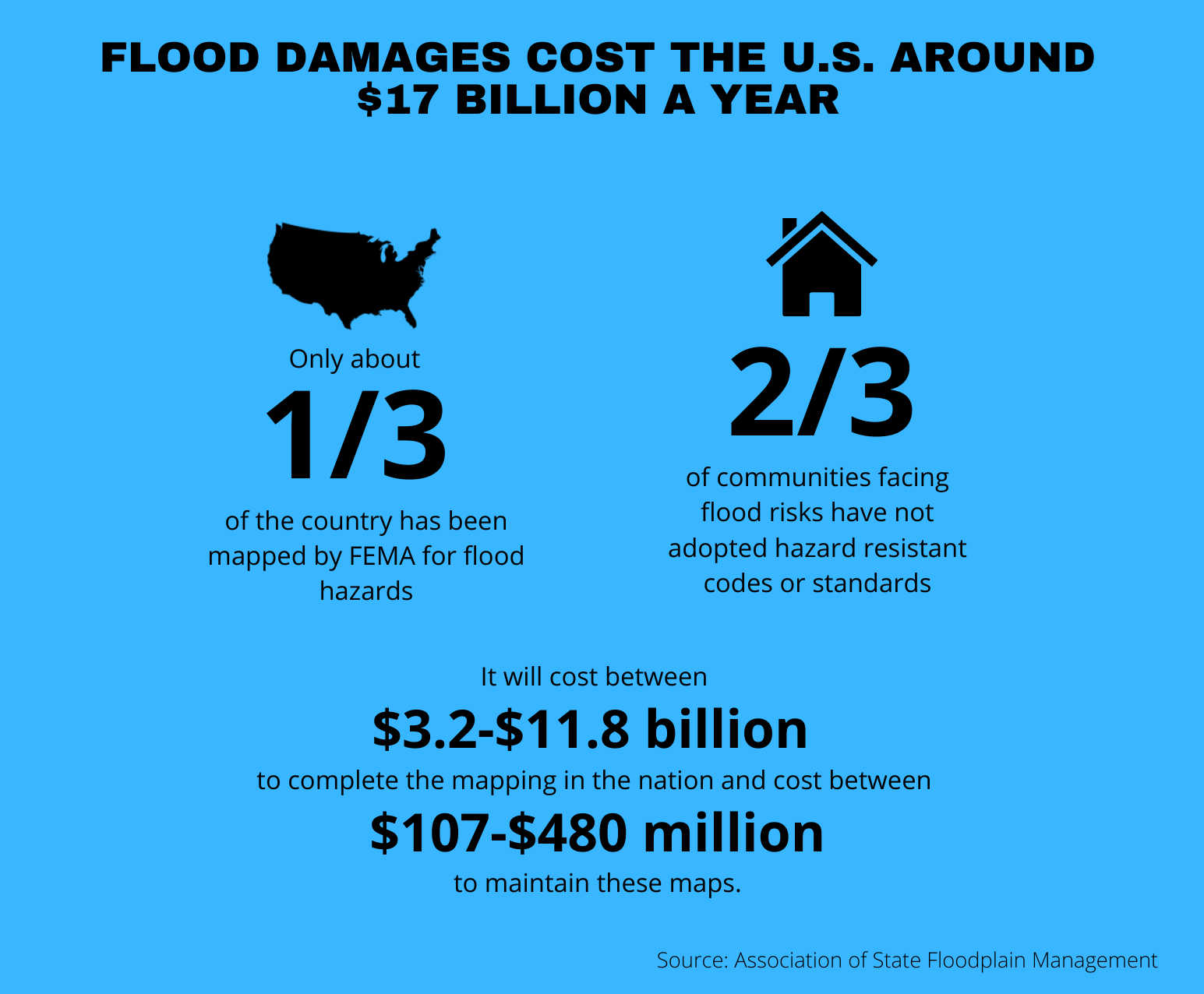

More than half of the country remains unmapped for flood hazards and around 15% of the communities that participate in NFIP have maps over 15 years old — many have maps over 30 years old, according to Jerry Hancock, stormwater and floodplain programs coordinator for the city of Ann Arbor, Michigan. Because flood mapping is funded through the financially distressed NFIP, FEMA doesn’t have the money to update maps quickly enough for communities to best defend themselves against severe storms, Hancock said.

Until recent years, the flood maps of Mohave County, Arizona, an NFIP participant that FEMA has designated to be at a relatively high risk of riverine flooding, had not been updated since the 1980s, according to Kat Fish, the county’s floodplain programs manager. Fish said the county has been able to update its maps through FEMA’s Cooperating Technical Partners program, through which the county received grants to study flood conditions in the area. Those conditions look a lot different now than four decades ago, Fish said.

Flood maps shape community planning and flood-mitigation efforts, Hancock said, by influencing the design and location of critical infrastructure like hospitals, transportation systems and storm drains. Local governments also use this information to create and update building codes, which can dictate the plots on which buildings can be built and how elevated a structure must be.

FEMA’s flood maps are a snapshot of the risk at the time the map becomes effective, according to a FEMA spokesperson. The agency includes sea level rise that has already happened in a community, for example, but it does not include how the sea level might rise in the future, the spokesperson said. If a community wants its flood map to show future conditions based on projected-land use, it must give FEMA information about land-use changes.

While developing and updating flood maps is time-consuming and costly, the agency is developing a new insurance pricing program designed to adapt to climate change, the spokesperson said. But if FEMA’s maps don’t accurately portray a community’s risk of flooding, Hancock said, the damages — which ultimately have to be covered by the federal government — will be more costly.

“Rules and regulations haven’t prevented people from building in harm’s way so there are more structures that can get damaged,” he said.

Currie from the GAO said the agency has urged Congress to dedicate more money to flood mitigation projects, including constructing levees and elevating homes, which would reduce the damages.

“The problem is, if you wait until after a disaster, then you really don’t have a choice in how much (money) you allocate because you’ve got to clean up the disaster,” Currie said. “It’s beforehand when you can help mitigate it and make it less worse the next time it floods.”