WASHINGTON– When Rachael Strickland found out in 2012 that her family’s school district was participating in a pilot program to store and manage student data, she was shocked.

“Gone are the days when we had the paper files down in a cabinet in the school’s main office with a lock and key,” said Strickland, a mother of two in Jefferson County, just outside Denver. “Now kids literally shed hundreds of thousands pieces of information about themselves everyday that are going outside and beyond the school’s walls.”

The $100 million program, funded by the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation, the Carnegie Corporation of New York and others, offered a warehouse service for public schools to store and manage student data ranging from test scores to which students received free lunches.

In January, as part of a movement to make sure a situation like Strickland’s doesn’t happen elsewhere, lawmakers in eight states and the District of Columbia introduced bills to give parents and students control over the new kinds of education data being collected. The American Civil Liberty Union organized the campaign to ensure protect personal data privacy for students.

For years, student data consisted of paper or electronic records — grading sheets, disciplinary records and attendance lists, for instance, that were created and stored by schools.

Today’s near ubiquity of computers and mobile devices in classrooms however, has brought with it an explosion in the amount of data that schools and service providers collect and keep about students.

For Strickland too much of that data was personal information, like family relationships and reasons for enrollment changes, collected from students without their consent. She and other parents were concerned the data could be sold to marketers or hacked. She led the charge against school district officials, who eventually dismantled the program.

After the decision to withdraw from inBloom, Colorado Education Commissioner Robert Hammon said the program taught state officials to engage more closely with the issue of student privacy.

“Using these tools, teachers would have been able to more easily support their students’ needs by helping them learn at their own pace and truly master a concept before moving forward,” Hammond said in a statement. “In my opinion, this continues to be an important goal in educating our students for the 21st century,” “Unfortunately, concerns and questions persisted in Jefferson County that led to their decision to withdraw from inBloom.”

The whole incident “spurred in a lot ways the whole national student privacy debate,” said Strickland who founded the Parent Coalition for Student Privacy and is one of its co-chairs. “It opened up the whole conversation not only amongst parents, but amongst policymakers and certainly in school districts and school boards across the country.”

The category of “student data” now contains not only the kind of data we’re used to thinking about: grades, demographic information, standardized test scores and disciplinary records, but also new kinds of data like how students interact with educational software, mobile applications and personal devices in real time. This data is stored either at schools or with third party providers of Student Information Systems like inBloom, the collection service used in Strickland’s school district.

The data allows teachers and policy makers to see immediate feedback and progress from students and learn what strategies and teaching methods work best.

However, the detail and volume of this data raises concerns from parents and advocates over who has access to it and how it is used.

The ACLU-drafted bills proposed in the eight states and Washington, D.C., aim to control who has access to Student Information Systems and data collected from the use of one-to-one devices– computers or tablets that are loaned to individual students.

But collecting that data has become a big industry that doesn’t see the need for more laws. The Software and Information Industry Association, the trade group that represents hundreds of technology and media companies, said in a statement that current regulation is sufficient.

The Pre K-12 educational technology sector was valued at $8.38 billion in February 2015, according to a report from the Software and Information Industry Association. And educational data profiles can stay with students for years, making them valuable assets for advertisers.

“While everybody’s data has value, in some respects, nobody’s data has more value than students,” said Chad Marlow, advocacy and policy counsel at the ACLU.

“Young people drive a lot of spending behavior,” said Marlow. “When people talk about whether a television show is a good place for advertisers to go, they don’t ask how many people watch it, they ask how many young people watch it.”

Many data advocates agree that student data, from test scores to browsing preferences on personal devices, should not be sold to advertisers in the way an adult’s Google searches and Amazon purchase history might be. However, for some, including Marlow, using data for some limited advertising, such as promoting a math tutor app to a student who needs extra help in the subject, might be a good thing.

Besides data being sold for advertising purposes and the possibility of third parties gaining access to information, some parents also worry that sensitive data — like behavioral histories or family situations — could be improperly shared within a school, potentially prejudicing staff or teachers against their students.

“I think that we need to be aware that we might make a comment in jest and it could affect a kid or the perception of somebody else about my kid because somebody made a mistake and disclosed some information about them that they shouldn’t have,” said Olga Garcia-Kaplan, a parent advocate who blogs at ferpasherpa.org, a project run by the Future of Privacy Forum, a Washington think tank.

Student data privacy has become a national issue. In the past two years, there have been over 300 bills introduced in 48 states regarding student data privacy laws, according to statistics from the National Association of State Boards of Education. Last year, 28 student data privacy bills became law in 15 states.

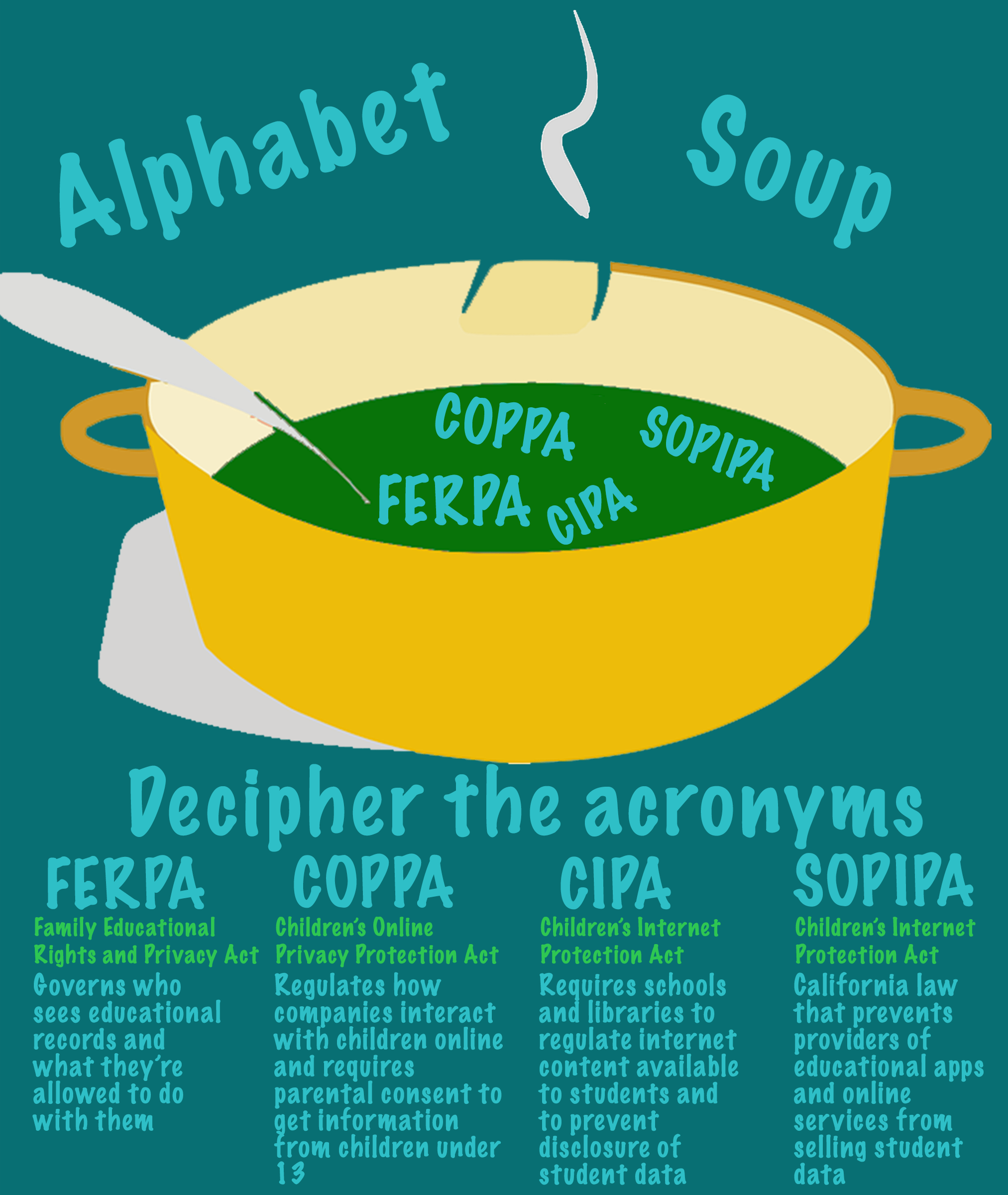

Those that became law, as well as federal laws like the Family Educational Rights and Privacy Act and the Children’s Online Privacy Protection Act, are part of a patchwork of rules that exists to protect the privacy of students through actions that include: preventing educational records specifically from being sold to advertisers, allowing parents to see and challenge these records and governing how advertisers can interact with children online.

However, most focus on more traditional educational data and were not written specifically to deal with modern data and its use in education.

The ACLU’s Marlow said the main objective of the ACU-drafted bills is to give parents and students the ability to choose who has their data and what they use it for.

“Privacy is about empowering people to make decisions for themselves,” he said.

The Software and Information Industry Association opposes “unnecessarily adding to a patchwork of state laws and federal regulations currently governing schools and service providers.”

“Creating separate rules and systems in different states risks limiting or even eliminating student access to advanced learning technologies that are essential to modern education.”

Instead of new laws, SIIA supports a pledge, signed by more than 240 companies including Apple and Google, that lays out what the signatories will and will not do with student data.

For Marlow, however, arguments that these new laws will stifle innovation are not genuine.

“There are definitely some profit-making opportunities for private companies that we’re not saying they can’t do, we’re just saying get permission,” he said.

And some student data privacy advocates think the ACLU approach could overwhelm parents and students.

“Parents shouldn’t be privacy auditors, it’s too much to put on a parent to decide whether this is good or bad,” Garcia-Kaplan said. “When you’re using an app in school and you’re letting parents decide if their kids can or cannot use an app, then you have 25 kids in a class and some are using it and some are not. How does a teacher negotiate all that?”

For our media presentation, please click here.