WASHINGTON — In 2007, the new district attorney of Dallas County partnered with the Innocence Project of Texas to review over 400 old cases, many involving denied requests for DNA testing, because the county had the highest number of wrongful convictions in the country.

To ensure such mistaken convictions never happened again, District Attorney Craig Watkins established the first conviction integrity unit in the United States later that year.

“We made history … I still get calls to my private office for individuals that want me to do that,” Watkins said this week of reviewing old cases, “but I don’t have the power to do that anymore.”

Watkins’ bid for reelection in 2014 was stifled by Susan Hawk amidst allegations of misused forfeiture funds, but his conviction integrity unit became a model for criminal justice in the country.

Today there are 24 county conviction integrity units within district attorneys’ offices nationwide — including those in Bexar, Dallas, Harris, Tarrant and Travis counties in Texas — that work to identify and correct false convictions.

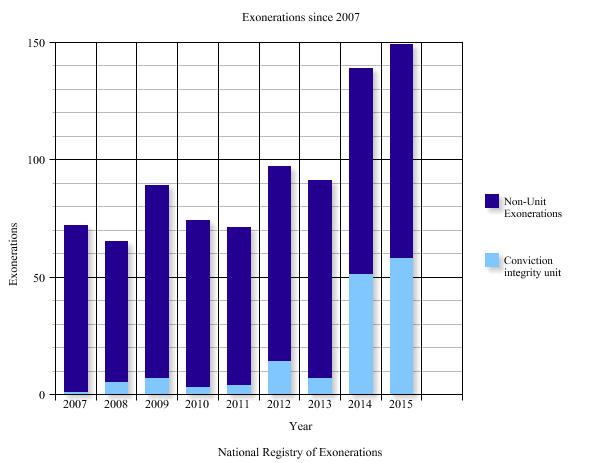

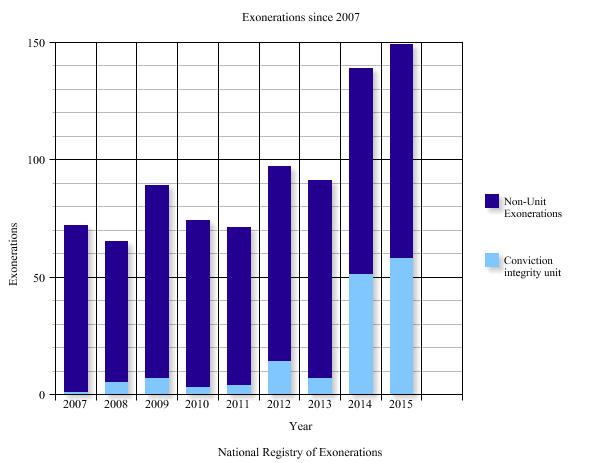

While they exist in less than 1 percent of the nation’s 3,007 counties, such units were responsible for 39 percent of overturned wrongful convictions in the U.S. last year, according to a report by the National Registry of Exonerations. That’s 58 of the record-high 149 exonerations in 2015.

The work of reporters and innocence projects has led to a series of exonerations involving the misuse of forensic information by law enforcement, said James Liebman, director of the Center for Public Research and Leadership at the Columbia Law School.

“There is a huge sensitivity now to the misuse of prosecutorial and police processes to convict people who are innocent,” Liebman said. “Officials have become sensitive to those (innocence) claims and are taking responsibility to do something about it.”

As a result, more district attorneys are starting their own units, said John Hollway, executive director of the Quattrone Center for the Fair Administration of Justice at the University of Pennsylvania Law School.

“As information has spread and (units) have gotten more praise and done more good, you see a rapid uptick,” Hollway said. “More than half of them were started in the last 24 months.”

The units spend a lot of time sorting through requests from the convicted parties, innocence projects and other sources to decide what to review, said Inger Chandler, chief of the Conviction Review Section at the Harris County District Attorney’s Office in Houston.

“We try to give every case its due diligence because the last thing you want to do is miss that needle in a haystack,” Chandler said. “Where we carve people out of eligibility for our review is that you have to be making a claim of actual factual innocence. In other words, ‘ I wasn’t there’ or ‘I was misidentified.’ Not a justification, not a lesser role, but factual innocence.”

The unit in Harris County was responsible for 42 of the 58 conviction integrity unit exonerations in the United States last year. Based on a tip, Chandler’s unit requested testing for hundreds of drug cases.

The Houston Forensic Science Center, which tests most DNA evidence and suspected drug evidence for the Houston Police Department, found dozens of cases over the last two years in which people were charged with possession or sale of controlled substances, but the substances were not actually illegal.

That resulted in the exoneration of 76 people, including Joseph Crochon, a 60 year-old man who plead guilty to possession of cocaine in Houston two years ago. A lab test found that the seized substance was not cocaine, and the charges were dismissed last month.

Samuel Gross, a co-founder of the National Registry of Exonerations and law professor at the University of Michigan, said “devoting resources to cases that they prosecuted and finished years, sometimes decades ago” is a relatively new idea for prosecutors. “It’s not that prosecutors have never been involved in exonerations, but that they make it a separate function, with employees that do nothing but that, is a new thing.”

Because they are located within county prosecutors’ offices, conviction integrity units are the only entities other than the police with access to the best evidence of wrongful convictions and the power to subpoena key witnesses, Liebman said.

“Prosecutors realized that if they don’t do the investigations themselves they are going to have to cough up that information,” he said. “And it may prove more embarrassing for journalists or the public to root around in all of that evidence rather than having (the units) do it in a more controlled way.”

But some district attorneys don’t favor such units because they could suggest that prosecutors aren’t scrutinizing the integrity of all of their convictions, Hollway said.

“An office that has a conviction integrity unit is sending a public signal that they treat (wrongful conviction) cases as important cases that deserve special attention,” he said. “That is a good thing, but it doesn’t mean that if you don’t have one that you are not taking (those cases) seriously.”

Only about 15 percent of Americans live in the jurisdiction of conviction integrity units, and over 60 percent of counties with more than 1 million people don’t have them, the National Registry of Exonerations report said.

And although the number of county conviction integrity units has grown, there has not been a corresponding interest at the state level. North Carolina is the only state with a version of the conviction integrity units.

Created by the General Assembly, the North Carolina Innocence Inquiry Commission covers the state’s 100 counties; its work has led to nine exonerations since it began operations in 2007.

“Our commission is called rather regularly by different states that are reviewing their own study commissions or looking into the model,” Executive Director Lindsey Guice Smith said. “I think a lot of times it comes down to resources for whether or not they choose to take that path.”

The North Carolina structure is effective because cases are getting handled in less populous counties that simply don’t have the resources to devote to conviction review in that context, Hollway said.

“The potential is for prosecutors and various jurisdictions to expand the conviction review process to ensure that there is a mechanism for the efficient review of any plausible case of actual innocence,” he said.

But Hollway, Liebman and other experts don’t expect other states to follow North Carolina’s lead any time soon.

“At this point I don’t see a national movement causing all 50 states to take strong action,” Liebman said. “But I do think we will see more activity taking place to assure the integrity of the convictions. However, it will probably continue to be very uneven from one city to the next and one state to the next.”